I TOLD THIS SMALL MAN: if I had a mule, a parachute and long, flowing locks, I would jump out of this plane, put you in my shopping cart and push you to Brazil where we would change our names, cut our hair, and join the local militia. After that, we would lead a small army of chickens to the sea and, after many days of floating, I would catch a small fish and name it Pavlov. Then we would all jump into the sea and swim until we reached the largest island in Europe, where we would start a mariachi band with my birth family and yours and the sun would set and we would all drink sugar water and go to sleep beneath a large curtain of black air.

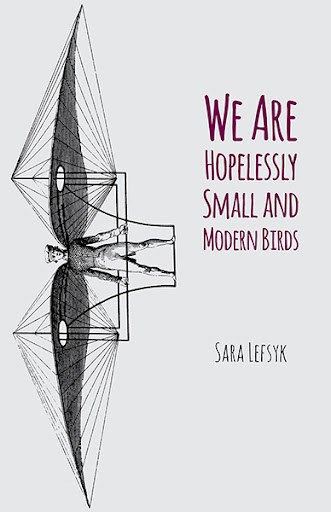

Thanks to the author, I recently acquired a copy of Ethel Zine maven Sara Lefsyk’s full-length debut, We Are Hopelessly Small and Modern Birds (New York NY: Black Lawrence Press, 2018), a book-length suite of prose poems writing (according to Jeff Friedman’s back cover blurb) “a small ward in a hospital the size of a universe, Heidigger, Kant, a small man who speaks in parables, numerous messiahs, hundreds of birds and animals, a strange doctor and his son, birds that need watering, and ‘pharmacological pancakes.’” Going through my files, it is curious to realize that a selection of the poems included here appeared previously in her chapbook A SMALL MAN LOOKED AT ME (Little Red Leaves, 2014), a title I reviewed (and very much enjoyed) soon after it appeared.

The prose poems in We Are Hopelessly Small and Modern Birds are curiously built, with each stanza-block existing as a single breath, a single thought, composing a semi-ongoing narrative amid lyric bursts. Through a lyric of surreal narratives, Lefsyk’s poem offer a story that exists in a shimmering dream-state, shifting in and out of focus. “OCCASIONALLY,” she writes, to open a poem early on in the collection, “OUR APARTMENT COMPLEX floats out to sea. As it was, Kant and I had our noses somewhere in the distance. ‘Most likely there is no meaning in things,’ Kant says. ‘Or only in the ultimate logic of certain animal forms and avian noises.’ // For this reason my bones feel like the small broken bones of a very tiny goldfish.” Set in five sections with an opening salvo, a poem-as-dedication “for and after FEDERICO GARCİA LORCA,” her narrator speaks from a ward and of doctors, dentists, husbands and philosophers in poems composed out of a kind of easy-flowing, clear and liquid motion. As well, there is something interesting about the way she writes of the body and the self, the narrator writing from a perspective that verges on primal, seen through a surreal lens. “IF I WERE A WIFE and a mother I would be a wife and a mother.” she writes, mid-way through the collection. “All my children say: ‘Build me,’ but the son takes my pelvis and runs it through the supermarket. // I go into and out of this supermarket whenever I want.” After having gone through this collection, I’m genuinely curious to find out what she’s been working on since.

IF THEY WERE COUNTING us all they were counting us all like they did yesterday only this time they would miss me in the numbers today.

Then they would force us onto our feet and we would pray for there not to be ropes and if there were ropes we would pray.

Arrange yourself.

The dr. himself would kneel before us and stick things places i can’t even talk about

and we won’t even cry a little about it.

They found my t-shirt but not me in it in the prayer room. They found my silence and my t-shirt and i did pray.

Bless me, they found my whole body in some dentist’s apartment and rotated it until they found its brilliance.

My upper jaw cit into my pelvis and i became some good factory.

No comments:

Post a Comment