Monday, June 30, 2014

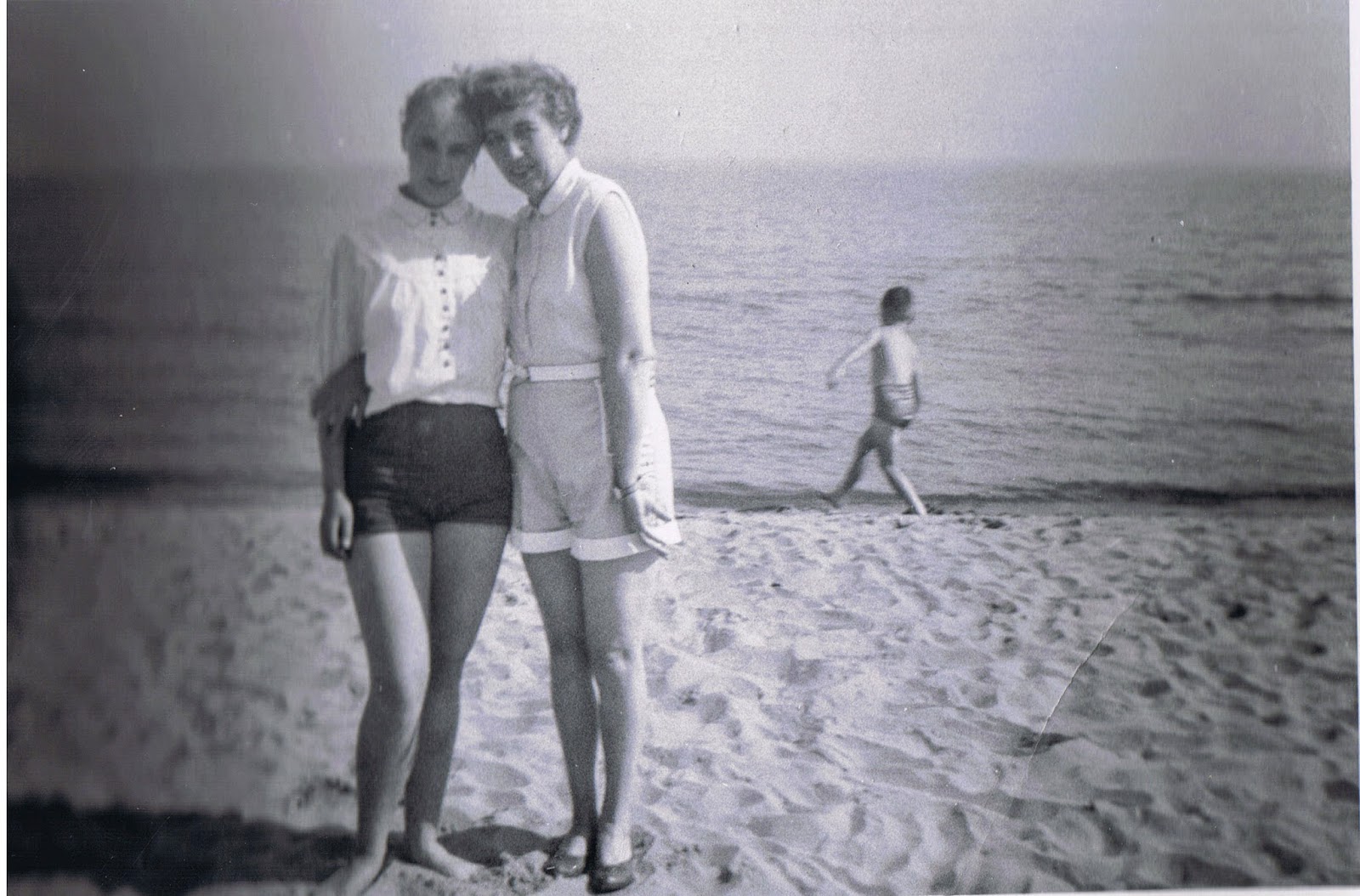

Today would have been my mother's seventy-fourth birthday,

Here she is on the beach in Cobourg, Ontario with her mother, during the summer of 1956. Mum's youngest sibling, Bob, splashing about behind them.

Labels:

birthday,

Cobourg,

grandmother,

McLennan genealogy,

mother

Sunday, June 29, 2014

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Jennifer Firestone

Jennifer Firestone is the author of Flashes (Shearsman Books) Holiday (Shearsman Books), Waves (Portable Press at Yo-Yo Labs), from Flashes and snapshot (Sona Books) and Fanimaly (Dusie Kollektiv). She is the co-editor of Letters To Poets: Conversations about Poetics, Politics and Community (Saturnalia Books), and an Assistant Professor of Literary Studies at Eugene Lang College (The New School). She lives with her family in Brooklyn.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

It didn’t. My first book, Holiday, began as something I wrote on part of a napkin during a trip. It took several years to fully conceptualize and develop. Then I had twins, and then I had a book. I was happy but it was just another event. Not to sound ungrateful, because I’m not, but I think there might be too much emphasis placed on the “first book.” Holiday was a very specific project in which I was deconstructing tourism, “master” artists/masterpieces, and ideas about the expectations and pressures of a vacation. My recent projects are more expansive; they’re less about specificity and more about layering and nuance. But the tracking of perception and the projections of perception is what’s kept constant. I’m also fascinated by the use of the camera as a way to zoom in and out of perceptions and track how things are staged or constructed. I think the camera has been a tool throughout my work.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

As trite as this may sound depression and sensitivity during my youth brought me to poetry. I wrote fiction also but the open and exploratory quality of poetry lured me in. Poetry helped me filter and mediate what was occurring in the world around me and my relationship to it all.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I work both slowly and quickly. To begin with I usually have a surplus of fragments hovering and then I work fast in a manic kind of way. I begin to fill in with notes and research—this takes time. I revise heavily as at some point I try to let go of aspects of my ego and accept what the poem is or hopes to be. I also periodically archive project ideas and slowly, slowly collect notes on those over several years until I start playing with them and seeing the project that might be evolving.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I have a more difficult time coming to the discrete poem but I’m doing it more lately as it is a challenge for me. I think serially and therefore write that way. I like the work to be able to stretch out its legs.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Yes public readings are crucial. I’m nervous reading my work but I do it often and am appreciative of the community event of a reading. I also “hear” the work in a different way when I’m reading in front of an audience. Usually the parts that are weak or disingenuous ring loud.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I don’t know how to write without theoretical concerns. I’m more drawn to the questioning aspects of writing than the answering. My concerns are always why a poem versus any other type of writing. I am curious to push at what makes me identify as a poet. I also am always working against the desire to play with language, sound and the page versus the “meaning” or intent (not that these variables are mutually exclusive), but I look at the posturing, the gesturing in a poem and wonder about it…where it comes from, how it arises, is it qualified, does it have to be. And of course the big question of why even bother, why poetry?

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Whoa. These large questions scare me. I don’t like the word “role.” It makes me feel I have a job of some sort and I’d rather work less than I do. On a very basic level I think we all have poetry (whether we know this or not) and poetry and poets can encourage people to think discursively, to stay in the place of investigation and questioning.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Definitely essential. I wish our culture had the means (maybe it’s interest too) in really editing each other’s work. I would welcome the insight and I think a lot of books could use some additional editing. And of course the relationship can be difficult between a writer and editor. Any collaboration is, right? You might think you’re a good communicator BUT… I will say though I am also quite interested in alternative publishing routes such as collectives and such.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Myung Mi Kim would speak about how a poem can absorb “invisible research” so that the ideas one might look into don’t always have t be so explicitly tacked on to a poem.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to critical prose)? What do you see as the appeal?

I like the exploratory form of an essay. I just need the prose to be flexible and meandering in its attempt at a trajectory. All my work is critically reflexive and so it excites me to hold on to my aesthetic and grapple with the demands of a particular form.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Oh gosh. I respect those who have a strict routine. My routine is really no routine. I have three small kids and so I write in jumps and fits. I’ve learned to be informed by this as a poetics of some sort—having to create within disjointedness. I presented a paper on this called “The Synergy of Poetics and Motherhood” for the Belladonna: Advancing Feminist Poetics And Activism Conference.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I read books, particularly poetry books, just flipping through them to sense the texture, visual layout etc. The look of a book can excite me or just reading words without context helps. I also generally want to write when I see art if the experience itself is not too sterilely institutional. Also geography helps. Going to a different place, different air, colors, hits the refresh button on my brain.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Cigar smoke.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Art makes me want to write. I just visited a Carrie Mae Weems exhibit at the Guggenheim and told my students to carry their notebooks and take “poetry notes.” I get into a very engaged but calm place around art. But really all materials/disciplines are up for grabs. I think a poet should mediate as many forms as possible.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Emily Dickinson, Kamau Brathwaite, Lyn Hejinian, Lorine Niedecker, Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Harryette Mullen, Gertrude Stein, Susan Howe, Charles Olson, Barbara Guest, John Ashbery, Edmond Jabès, Paul Celan and many others.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Maybe perform. Actually I am performing now in a new performance art group that I co-founded called Wonder Machine, and I think in an ideal world I’d even go more in that direction. I took drama when I was very young as it was sort of the place for drifters, weirdos, etc. I’d like to sing and just push the edge of what I can do performatively but that still has artistic value to me.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Well I guess I’d be a shrink. I mean I think I’d be a good one but I’d probably get too wrapped up in people’s stuff. I do it now as is.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I realized writing was a site of investigation, querying and plotting that I didn’t find the space for in other areas. It felt generous and in a way unyielding which perpetually keeps me challenged.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Joseph Harrington’s Things Come on. I haven’t seen a film that’s wowed me in a long time. What jumps in my head is Breaking the Waves. Oh but the documentary Blackfish is really strong and hard to watch.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I’m working on the collaboration that I mentioned previously which involves text that I wrote, photographs from urban geographer Laura Y. Liu, sound by composer and musician Daniel Goode and performance by noted feminist and writer Ann Snitow. I’m also writing a long poem entitled Story, which is the telling of a particularly harrowing event that happened at a beach while simultaneously the telling and resisting telling of how that story is constructed. Last, I’m working on a manuscript of poems that investigates the icon Mother Goose and its publishing history.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

It didn’t. My first book, Holiday, began as something I wrote on part of a napkin during a trip. It took several years to fully conceptualize and develop. Then I had twins, and then I had a book. I was happy but it was just another event. Not to sound ungrateful, because I’m not, but I think there might be too much emphasis placed on the “first book.” Holiday was a very specific project in which I was deconstructing tourism, “master” artists/masterpieces, and ideas about the expectations and pressures of a vacation. My recent projects are more expansive; they’re less about specificity and more about layering and nuance. But the tracking of perception and the projections of perception is what’s kept constant. I’m also fascinated by the use of the camera as a way to zoom in and out of perceptions and track how things are staged or constructed. I think the camera has been a tool throughout my work.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

As trite as this may sound depression and sensitivity during my youth brought me to poetry. I wrote fiction also but the open and exploratory quality of poetry lured me in. Poetry helped me filter and mediate what was occurring in the world around me and my relationship to it all.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I work both slowly and quickly. To begin with I usually have a surplus of fragments hovering and then I work fast in a manic kind of way. I begin to fill in with notes and research—this takes time. I revise heavily as at some point I try to let go of aspects of my ego and accept what the poem is or hopes to be. I also periodically archive project ideas and slowly, slowly collect notes on those over several years until I start playing with them and seeing the project that might be evolving.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I have a more difficult time coming to the discrete poem but I’m doing it more lately as it is a challenge for me. I think serially and therefore write that way. I like the work to be able to stretch out its legs.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Yes public readings are crucial. I’m nervous reading my work but I do it often and am appreciative of the community event of a reading. I also “hear” the work in a different way when I’m reading in front of an audience. Usually the parts that are weak or disingenuous ring loud.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I don’t know how to write without theoretical concerns. I’m more drawn to the questioning aspects of writing than the answering. My concerns are always why a poem versus any other type of writing. I am curious to push at what makes me identify as a poet. I also am always working against the desire to play with language, sound and the page versus the “meaning” or intent (not that these variables are mutually exclusive), but I look at the posturing, the gesturing in a poem and wonder about it…where it comes from, how it arises, is it qualified, does it have to be. And of course the big question of why even bother, why poetry?

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Whoa. These large questions scare me. I don’t like the word “role.” It makes me feel I have a job of some sort and I’d rather work less than I do. On a very basic level I think we all have poetry (whether we know this or not) and poetry and poets can encourage people to think discursively, to stay in the place of investigation and questioning.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Definitely essential. I wish our culture had the means (maybe it’s interest too) in really editing each other’s work. I would welcome the insight and I think a lot of books could use some additional editing. And of course the relationship can be difficult between a writer and editor. Any collaboration is, right? You might think you’re a good communicator BUT… I will say though I am also quite interested in alternative publishing routes such as collectives and such.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Myung Mi Kim would speak about how a poem can absorb “invisible research” so that the ideas one might look into don’t always have t be so explicitly tacked on to a poem.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to critical prose)? What do you see as the appeal?

I like the exploratory form of an essay. I just need the prose to be flexible and meandering in its attempt at a trajectory. All my work is critically reflexive and so it excites me to hold on to my aesthetic and grapple with the demands of a particular form.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Oh gosh. I respect those who have a strict routine. My routine is really no routine. I have three small kids and so I write in jumps and fits. I’ve learned to be informed by this as a poetics of some sort—having to create within disjointedness. I presented a paper on this called “The Synergy of Poetics and Motherhood” for the Belladonna: Advancing Feminist Poetics And Activism Conference.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I read books, particularly poetry books, just flipping through them to sense the texture, visual layout etc. The look of a book can excite me or just reading words without context helps. I also generally want to write when I see art if the experience itself is not too sterilely institutional. Also geography helps. Going to a different place, different air, colors, hits the refresh button on my brain.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Cigar smoke.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Art makes me want to write. I just visited a Carrie Mae Weems exhibit at the Guggenheim and told my students to carry their notebooks and take “poetry notes.” I get into a very engaged but calm place around art. But really all materials/disciplines are up for grabs. I think a poet should mediate as many forms as possible.

Emily Dickinson, Kamau Brathwaite, Lyn Hejinian, Lorine Niedecker, Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Harryette Mullen, Gertrude Stein, Susan Howe, Charles Olson, Barbara Guest, John Ashbery, Edmond Jabès, Paul Celan and many others.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Maybe perform. Actually I am performing now in a new performance art group that I co-founded called Wonder Machine, and I think in an ideal world I’d even go more in that direction. I took drama when I was very young as it was sort of the place for drifters, weirdos, etc. I’d like to sing and just push the edge of what I can do performatively but that still has artistic value to me.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Well I guess I’d be a shrink. I mean I think I’d be a good one but I’d probably get too wrapped up in people’s stuff. I do it now as is.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I realized writing was a site of investigation, querying and plotting that I didn’t find the space for in other areas. It felt generous and in a way unyielding which perpetually keeps me challenged.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Joseph Harrington’s Things Come on. I haven’t seen a film that’s wowed me in a long time. What jumps in my head is Breaking the Waves. Oh but the documentary Blackfish is really strong and hard to watch.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I’m working on the collaboration that I mentioned previously which involves text that I wrote, photographs from urban geographer Laura Y. Liu, sound by composer and musician Daniel Goode and performance by noted feminist and writer Ann Snitow. I’m also writing a long poem entitled Story, which is the telling of a particularly harrowing event that happened at a beach while simultaneously the telling and resisting telling of how that story is constructed. Last, I’m working on a manuscript of poems that investigates the icon Mother Goose and its publishing history.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Saturday, June 28, 2014

Friday, June 27, 2014

Jim Shepard, Master of Miniatures

The year before, Tsuburaya had forced Tanaka to go see

his beloved King Kong, which had just

earned four times as much in its worldwide re-release as it had originally, and

Tanaka had also been impressed by the global numbers for Warner Brothers’ The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms, the story

of a dinosaur thawed from its hibernation by American nuclear testing in Baffin

Bay.

The United States government estimated that 856 ships in

the Japanese fishing fleet had been exposed to radiation, and that more than

five hundred tons of fish had to be destroyed, and offered a settlement for the

survivors that the Japanese government declined to accept. Tanaka recounted

that it struck him as he looked out over the Pacific below that the stories

could be combined; and for the rest of the flight he scribbled on the back of a

folder that his seatmate had lent him the outline of a story in which a

prehistoric creature was awakened by an H-bomb test in the Pacific and then

went on to destroy Tokyo.

Prior

to receiving a copy of his short novella, Master of Miniatures (New York NY: Solid Objects, 2010), I’d not heard of American writer Jim Shepard, author of more than a half-dozen titles of prose

(including, apparently, the novel Nosferatu,

which imagines the life of filmmaker F.W. Murnau). Emotionally complex,

haunting and deceptively straightforward in terms of narrative prose style, Master of Miniatures writes out the

story of the filmmaker Eiji Tsuburaya who, almost immediately after the ends of

the Second World War, wrote and directed the original version of the now-legendary Godzilla, released as Gojira (1954). While imagining the

details of the protagonist, Shepard’s novel manages to encompass in a

remarkably short space the details of the film’s creation, which itself works through

the savage trauma of an entire culture and country, and that of a single character,

from Tsuburaya recollecting his father’s survival of the “great earthquake” to

the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki that ended the Second World War. Through

his own attention to miniature, Shepard writes out Tsuburaya’s miniatures,

through which the filmmaker was able to respond to the large wounds that

existed across both him and his country, even while managing to lose sight of

his own life, and that of his wife and children. Through attempting to remove a

dark stain or shadow that couldn’t be removed, it is as though Tsuburaya simply

created yet another, even while managing to create a new cinematic form, still

deeply embedded in American culture. Shepard’s descriptions of the 1923

earthquake is quite chilling, and it is interesting that it is here that

Shepard decides to focus some of the worst images on this event, as opposed to possibly-expected

depictions of post-bombing Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Two policemen agape on a refugee’s cart were blown away. Tsuburaya’s

father was knocked down and blasted along the ground until his hand caught onto

something. A teenaged girl on fire flew by over his head. Human beings all

around him were sucked into the air like sparks. He shut his eyes against the

wind and heat. A tree was wrenched from the ground, roots and all, before him,

and he crawled into the loose earth and was able to breathe. Some ruptured

water mains there had created a bog, and he tunneled into the mud.

When he revived, the backs of his hands had been turned

to the bone. Everyone was gone. The skin atop his head was gone. His ears were

gone. Something beside him he couldn’t recognize was still squirming.

Through

Master of Miniatures, Shepard writes

out a man who masters both filmmaking and miniatures, as well as a number of

personal losses from which he can never recover. Shepard shows just how much

the trauma of what Tsuburaya had lived through had permanently changed him, a

realization he doesn’t entirely comprehend, and one that he begins to suspect

far too late. This is a deeply fulfilling and unsettling novel, one that doesn’t

end well or let easily go.

In the

rushes of the final scenes, Honda noted how sad Gojira looked when he turned

from the camera.

“That’s the

way I made the mask,” Tsuburaya reminded him.

“No,” Honda

said. “The face itself is changing through the context of what we’ve seen him

go through. By the time the movie ends he’s like a hero whose departure we

regret. The paradox of fearsomeness and longing is what the whole thing’s about.”

“I wouldn’t know

about that,” Tsuburaya told him.

“It’s like

part of us leaving,” Honda said. “That’s

what makes it so hard. The monster the child knows best is the monster he feels

himself to be.” After Tsuburaya didn’t respond, he added, “That’s why I love

those shots of the city after the monster’s gone. All that emptiness, like a

no-man’s land in which eloquence and silence are joined. If you don’t have

both, the dread evaporates.”

That was

true, Tsuburaya conceded. He volunteered that he was particularly proud of the

shots of the harbor at night before the creature’s eruption from the sea: all

along the waterfront, silence. Silence like thunder.

Thursday, June 26, 2014

Today is my father's seventy-third birthday

Today is my father's seventy-third birthday. Four-thirty in the morning, I believe.

My sister claimed he didn't want to acknowledge that he was/is getting older (I'd rather it than the other option), so we went to see him on the farm for Father's Day instead. We still celebrated with candles and a cake. Cake!

Unfortunately, Kate couldn't come this year, given her work schedule, but the rest of us managed an evening out at my sister's little house. We even brought home far too much fresh rhubarb, as well as some plants with roots for our own garden, as one of their neighbours was planning on ripping it all out of their own garden anyways. Rose laughed, complained a bit, and ate all of her green beans (a new item).

Before we left the farm, my father pulled out a trunk from the garage, one left over from his mother-in-law (my grandmother). Opening the trunk, we discovered it was far older than that, and belonging to my great-aunt Belle McLennan, who died in the late 1970s. We found her copy of a photo I'd been twenty years trying to get a copy of, sitting in a trunk in the garage the whole time.

Ah well. At least I have a copy of the portrait now. And an original, at that.

Happy Birthday. Here is my father as a wee babe with his own father. Most likely taken in the house my father still lives in (it does look slightly familiar as the kitchen, looking towards the living room).

My sister claimed he didn't want to acknowledge that he was/is getting older (I'd rather it than the other option), so we went to see him on the farm for Father's Day instead. We still celebrated with candles and a cake. Cake!

Unfortunately, Kate couldn't come this year, given her work schedule, but the rest of us managed an evening out at my sister's little house. We even brought home far too much fresh rhubarb, as well as some plants with roots for our own garden, as one of their neighbours was planning on ripping it all out of their own garden anyways. Rose laughed, complained a bit, and ate all of her green beans (a new item).

Before we left the farm, my father pulled out a trunk from the garage, one left over from his mother-in-law (my grandmother). Opening the trunk, we discovered it was far older than that, and belonging to my great-aunt Belle McLennan, who died in the late 1970s. We found her copy of a photo I'd been twenty years trying to get a copy of, sitting in a trunk in the garage the whole time.

Ah well. At least I have a copy of the portrait now. And an original, at that.

Happy Birthday. Here is my father as a wee babe with his own father. Most likely taken in the house my father still lives in (it does look slightly familiar as the kitchen, looking towards the living room).

Labels:

birthday,

father,

McLennan genealogy,

Rose McLennan

Wednesday, June 25, 2014

Pearl Pirie, Quebec Passages

My short review of Pearl Pirie's Quebec Passages (2014) is now online at The Small Press Book Review.

Tuesday, June 24, 2014

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Brian Henderson

Brian Henderson is the author of 10 collections of poetry, one of which, Nerve Language, was a finalist for the Governor General’s Award and about which the jury wrote, “Terrifying and beautiful, the language…is an incendiary crossing of wires. These poems are as likely to break you open as they are to explode.” His latest, Sharawadji, was a finalist for the Canadian Authors Association Award for Poetry. A new volume, [OR] is forthcoming from Talon. He is the director of WLUPress.

1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

First book was in the Precambrian, so the flora & fauna were quite different & the weather a lot warmer, if memory serves, but I enjoyed actually working through preparing the thing for publication at Porcupine’s Quill with Tim & Elke & my editor John Flood. To see it in print rendered all the writing towards it into a different kind of physicality from the notebooks & pens I was used to to an object that still somehow was not a product. Books are rather strange that way, don’t you think? But that objectification was a confirmation: I knew there was a path, even if I were going to have to make it up as I went along.

At the launch party in our house I remember Frank Davey saying something to effect of “It’s a very interesting book, but what does it mean?” So in some ways perhaps through all the intervening years I’ve always been writing at the margins — not in the sense of a radical poetics necessarily, but informed by some of that. Not in the experimental school completely & not in the lyric anecdotal school either.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

When I was young I wanted to be a composer (of all things!), but having no musical training at age 14, I somehow ended up scribbling lines of words; these happened to embody some rhythmicality which I sort of liked. And then the work of Dylan Thomas found me.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

This really depends on the “project” -- if indeed there is one. If there is, the writing can often be a slalom. I love reading & am always reading so any research is not necessarily done beforehand but hand in hand. If there isn’t a project, then things tend to move a little slower & accumulate. This is a more sedimentary & less metamorphic process.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

A poem begins in a phrase, line or an image -- & by “image” I mean a trope, not a visual “picture” & certainly not a story, & even less does it begin with “something to say”.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I find with readings that the personality of the reader often gets in the way & of course there’s no opportunity to sit with a line or something, so I’m not a big fan. I’m not a voice oriented writer — I never consciously went out looking for my own voice for instance. And I’m not by nature a performer. I relish the page & what writing does.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

This is a really complex question disguised as a simple one. Can I just answer “Yes”? The difficulty I have here is that the specifics of my concerns are shifting. But maybe generally I can address this by saying that I’m fascinated by the presence/absence paradox that is borne out in writing. So concerns about representation, materiality, the imaginary of meaning (& meaning as commodification), especially in the context of reading & how perception & memory cover over their hallucinatory basis. I’m interested — let’s put it in Lacanian terms -- in that remainder, that left over, that lies outside the realm of the Symbolic which might therefore show us something of the Real. How the non-place of language opens a gap in the world, in that place where, as Ian Bogost has written: “wonder darkens”.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Wow. Another large question. Well if (most) media coverage is anything to go by, the role of the writer in society today is entertainer, or possibly educator or insight giver on some topic or issue or other, or maybe wisdom guide on the path of life. Nothing wrong with these roles. But. And the writing I like says “But”, or “What if”. Sometimes just “Not”.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I think it’s essential that some other sets of synapses get to work on a work in progress; it’s not certainly just a question of another set of eyes. I’ve been lucky: my editors have been ideal readers, asking questions from inside the work, saying “but” & “what if”.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?“Be spear. Be spear.” Rilke.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to critical prose)? What do you see as the appeal?

I’ll skip this one since I don’t move between genres, except when I’m reading.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I’m a working stiff, so it’s the office for me. I have no writing routine, but I’m always reading, & I have Evernote ever at the ready!

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Books, books books. Poetry, cultural theory, science studies, the odd novel — & usually “odd” is right.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Cedar. We’re engulfed in cedar trees here in our spot in the Grey Highlands. And smoke. It’s great to have a wood burning fireplace again. But not cedar in the fireplace; elm.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Frye also said that I think. But yeah, all the above -- & junk yards, hardware stores, storerooms, warehouses, old post-industrial areas of cities.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I’ve really been enjoying Arkadii Dragomoshchenko & Brian Massumi recently.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I think maybe I’d like to canoe the Nahanni one of these days before it’s too late.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I might have stuck with being a drummer, but the routine universe of bars started to take it’s toll. Maybe a prof of CanLit, but when I graduated there were no jobs in the field for 5 years & by then I had moved on.

But really, if I weren't writing, perhaps I’d not be interested in any of these kinds of things and I’d be standing in Amazonian tributary tagging tetras.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Bad luck? My father said laziness once, but then he liked to play guitar. Nope, I think it’s the sense of surprise at the weirdness & rightness that comes about (at the same time) in that non-place (of writing) when the writing is flying & something new pop’s out. Particularly if I don’t completely understand it. So it’s probably serotonin.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Tarkovsky’s Stalker. Marcus’s The Flame Alphabet, or maybe Murakami’s 1Q84. No maybe it was Massumi’s Parables for the Virtual, or hold it, Jane Draycott, Open. rob, I give up.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I’m working on a book of things I guess you could say. Many of the poems are lists of things. Lists which try to highlight how alien things are, the things we take so much for granted. They try to tear small holes in the taken-for-granted. They try to peel away what we might know to leave a narrative of debris. They strip the narrative to reveal the thing & the thing to reveal the narrative. "Objects may be custodians of our narratives" Peter Schwenger says in The Tears of Things; objects may also refuse (our) narratives (& invent their own). Are things really dead? I think maybe it’ll be a book of still life.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

First book was in the Precambrian, so the flora & fauna were quite different & the weather a lot warmer, if memory serves, but I enjoyed actually working through preparing the thing for publication at Porcupine’s Quill with Tim & Elke & my editor John Flood. To see it in print rendered all the writing towards it into a different kind of physicality from the notebooks & pens I was used to to an object that still somehow was not a product. Books are rather strange that way, don’t you think? But that objectification was a confirmation: I knew there was a path, even if I were going to have to make it up as I went along.

At the launch party in our house I remember Frank Davey saying something to effect of “It’s a very interesting book, but what does it mean?” So in some ways perhaps through all the intervening years I’ve always been writing at the margins — not in the sense of a radical poetics necessarily, but informed by some of that. Not in the experimental school completely & not in the lyric anecdotal school either.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

When I was young I wanted to be a composer (of all things!), but having no musical training at age 14, I somehow ended up scribbling lines of words; these happened to embody some rhythmicality which I sort of liked. And then the work of Dylan Thomas found me.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

This really depends on the “project” -- if indeed there is one. If there is, the writing can often be a slalom. I love reading & am always reading so any research is not necessarily done beforehand but hand in hand. If there isn’t a project, then things tend to move a little slower & accumulate. This is a more sedimentary & less metamorphic process.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

A poem begins in a phrase, line or an image -- & by “image” I mean a trope, not a visual “picture” & certainly not a story, & even less does it begin with “something to say”.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I find with readings that the personality of the reader often gets in the way & of course there’s no opportunity to sit with a line or something, so I’m not a big fan. I’m not a voice oriented writer — I never consciously went out looking for my own voice for instance. And I’m not by nature a performer. I relish the page & what writing does.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

This is a really complex question disguised as a simple one. Can I just answer “Yes”? The difficulty I have here is that the specifics of my concerns are shifting. But maybe generally I can address this by saying that I’m fascinated by the presence/absence paradox that is borne out in writing. So concerns about representation, materiality, the imaginary of meaning (& meaning as commodification), especially in the context of reading & how perception & memory cover over their hallucinatory basis. I’m interested — let’s put it in Lacanian terms -- in that remainder, that left over, that lies outside the realm of the Symbolic which might therefore show us something of the Real. How the non-place of language opens a gap in the world, in that place where, as Ian Bogost has written: “wonder darkens”.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Wow. Another large question. Well if (most) media coverage is anything to go by, the role of the writer in society today is entertainer, or possibly educator or insight giver on some topic or issue or other, or maybe wisdom guide on the path of life. Nothing wrong with these roles. But. And the writing I like says “But”, or “What if”. Sometimes just “Not”.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I think it’s essential that some other sets of synapses get to work on a work in progress; it’s not certainly just a question of another set of eyes. I’ve been lucky: my editors have been ideal readers, asking questions from inside the work, saying “but” & “what if”.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?“Be spear. Be spear.” Rilke.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to critical prose)? What do you see as the appeal?

I’ll skip this one since I don’t move between genres, except when I’m reading.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I’m a working stiff, so it’s the office for me. I have no writing routine, but I’m always reading, & I have Evernote ever at the ready!

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Books, books books. Poetry, cultural theory, science studies, the odd novel — & usually “odd” is right.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Cedar. We’re engulfed in cedar trees here in our spot in the Grey Highlands. And smoke. It’s great to have a wood burning fireplace again. But not cedar in the fireplace; elm.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Frye also said that I think. But yeah, all the above -- & junk yards, hardware stores, storerooms, warehouses, old post-industrial areas of cities.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I’ve really been enjoying Arkadii Dragomoshchenko & Brian Massumi recently.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I think maybe I’d like to canoe the Nahanni one of these days before it’s too late.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I might have stuck with being a drummer, but the routine universe of bars started to take it’s toll. Maybe a prof of CanLit, but when I graduated there were no jobs in the field for 5 years & by then I had moved on.

But really, if I weren't writing, perhaps I’d not be interested in any of these kinds of things and I’d be standing in Amazonian tributary tagging tetras.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Bad luck? My father said laziness once, but then he liked to play guitar. Nope, I think it’s the sense of surprise at the weirdness & rightness that comes about (at the same time) in that non-place (of writing) when the writing is flying & something new pop’s out. Particularly if I don’t completely understand it. So it’s probably serotonin.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Tarkovsky’s Stalker. Marcus’s The Flame Alphabet, or maybe Murakami’s 1Q84. No maybe it was Massumi’s Parables for the Virtual, or hold it, Jane Draycott, Open. rob, I give up.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I’m working on a book of things I guess you could say. Many of the poems are lists of things. Lists which try to highlight how alien things are, the things we take so much for granted. They try to tear small holes in the taken-for-granted. They try to peel away what we might know to leave a narrative of debris. They strip the narrative to reveal the thing & the thing to reveal the narrative. "Objects may be custodians of our narratives" Peter Schwenger says in The Tears of Things; objects may also refuse (our) narratives (& invent their own). Are things really dead? I think maybe it’ll be a book of still life.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Monday, June 23, 2014

Amy Lawless, My Dead

Sometimes a slew of

elephants die,

And you’re dealing with

what is called a massacre,

When three thousand die

maybe you have to just

Watch a movie.

It reminds me of

biology class in eleventh grade.

The combination of math

And chemistry were too

much and, boy, I gave up.

Mourning a grandmother

is one thing.

Mourning three thousand

someone’s child is too much,

But we do it anyway by

Watching some DVD until

it’s over

And then letting it sit

on the coffee table for a week

Until you can get out

of bed and look at it

Not recognizing that

this cultural artifact will always be the thing I did

Instead of watch news

that day in September.

I’m

absolutely floored by the work in Amy Lawless’ second trade poetry collection, My Dead (Octopus Books, 2013), a

follow-up to her first collection, Noctis Licentia (Black Maze Books, 2008), from the first poem I read, flipping

randomly to catch the piece I quote, above. Constructed out of four poem-sections—“Elephants

in Mourning,” “One Way to Write a Sonnet is to Number the Lines,” “Shadow Self”

and “The Skull Behind My Face”—there is a sharp and sassy brilliance to the poems

in My Dead, a cadence of rough work

and a brutal honesty in the way she carefully and precisely bares some pretty

raw emotion. As she writes in the first section, an extended lyric sequence of

short fragments: “Sometimes a man dies and his people gather around and eat

chips and / laugh about the things the dead man would do and say. His house was

his / crib and he never left it. His house was his African plain.” There is a way Lawless writes about loss, grieving and her many dead in a careful, open

rage, a flailing precision that blends to become something quite powerful.

This is the hind

elephant foot tapping at the carcass. This is the lover rolling the body over to

bring her back to life. This is the head lifted toward the sky trilling its

trunk. This is looking at photographs of you and your grandparents trying to

find a string between you. Here’s a newspaper you can’t read. This is what

happens here on Earth and I don’t need a bible. The sound I make dying is the

sound I make when I was born. Shaking and pink, I last for ages.

In

the second section, she composes eight sonnets each with the same title as the

section itself, playing with the form and too-often sincerity and seriousness

of the sonnet, and the idea of numbering (literally) the lines. The final poem of

the section opens: “1. Fuck off: I’m a poet. You ate my / 2. emotional energy

like cipher beetles / 3. down my neck.”

PORTICO

You drew me onto a

portico and said This is for you. It

was a beautiful necklace—rock hanging below cardinal numbers zero through nine.

I held it and Thank you. You sat on a

bench. Walls closed around us like in a car. It felt better than kissing some people

but worse than kissing others. You can do

whatever you want, you said. This was an explicit reference to your penis.

I held it and said This is bigger than

you’ve led me to believe it would be. You

can do whatever you want with it, you said. I stroked it, your eyes

appealed. First, I picked off a fine piece of crust.

The

third section plays with longer lines, longer stanzas and a deeper density,

stretching to see just how far her cadences might extend. As she writes to open

the longer poem “Barren Wilderness”: “see the world for what it is / maybe the

subtlety of the dry branches reaching to

the hawks / with bony hands[.]” Or the opening of the title poem itself: “The

car exploded for some political reason / I saw a monkey falling asleep in the

water / a monk meditating and praying / a girl doing laundry[.]” Lawless’ My Dead contains a clear eye, wild

energy and emotional rawness paired with a straightforward narrative thrust in poems

that seem almost dangerous, akin to works by Heather Christle, Paige Ackerson-Kiely and Bianca Stone for their formal care and emotional edge. There

is something magnificent going on here. Pure and simple.

Sunday, June 22, 2014

a (new) little interview;

There's a new little interview with me on The Uncertainty Principle: stories, (2014), conducted by David Prosser, now online at barsetshirediaries.

Saturday, June 21, 2014

Ongoing notes: the ottawa small press book fair (part one)

[Rachael Simpson of In/Words and Nina Jane of & Co. Collective] Another small press book fair come and gone. This fall, if you can believe it, will be the

twentieth anniversary of our little event. How did we get here?

Ottawa ON: I’m

intrigued by Chris Johnson’s Down Bank:

Ex Haibun (2014), a small folded chapbook produced through Carleton University’s In/Words magazine and press [see the profile I wrote on them over at Open Book: Ontario]. Composed as ten haibun written about an

ex-girlfriend, Johnson skirts the line between some very fine writing and a

simple re-telling of a post-breakup narrative. This provides for a pretty

uneven series of pieces, but the sections that work are really quite lovely,

especially when Johnson worries less about telling the story of how the breakup

was hard and more about focusing the language on a particular small moment,

stretched out across a couple of lines.

EX

HAIBUN Nº 2

When I said my foreskin

tore the last time we had sex and there was blood stains on the bed, I meant

your body is earthly and I have spilt blood into the thickening of your skin, tissue of skin, torn for another

planting, another seeding, and you never saw red until I called you honey, you also carried on your back yin and

embraced yang with your arms and shoulders, you were balanced perfectly, my

friends complimented your breasts when we went skinny-dipping in my friend’s

inflatable pool, equal parts attractive and classy, and still you hid your

tattoos for your grandmother’s funeral; honey, did the bees make you?

Test,

what day is today, hungry, who has not eaten in days

It

has been interesting to watch Johnson play with form and influence, from this chapbook

of haibun (referencing Fred Wah, who also worked with the form) as well as an

earlier chapbook that came out of his reading the work of Phyllis Webb [see my review of such here]. I like the exploration of these pieces, and the places his

writing attempts, far more ambitious than most of the poets around him. Despite

the unevenness of this small item, I think I would recommend Down Bank: Ex Haibun; Chris Johnson is a

young poet worth paying attention to. Who knows what he might come up with

next?

[Michael e. Casteels talking to Pearl Pirie] Kingston ON: Cobourg,Ontario poet, editor and publisher Stuart Ross continues his curious engagement

with the poodle in Nice Haircut, Fiddlehead (Puddles of Sky Press, 2014), a chapbook of twelve short lyric

poems. Admittedly, the most his ongoing muse, the mysterious poodle, appears in

the collection is on the cover, but any follower of Ross’ work knows well

enough to not simply pass over such a reference. Do I make too much of this?

ELEGY

Nice haircut,

fiddlehead,

juggling beneath

a slobbering dog

by the side

of a gold-veined

lake.

Ross’

poems are constructed out of a series of moments, composed nearly as single,

stand-alone points, that accumulate and build into pieces that one can’t even

imagine, or easily describe. His ongoing engagement with humour and the surreal

often work as a kind of distraction, allowing Ross to work through what he is

really doing within a particular poem, leaving the reader with something striking,

powerful and sometimes slightly sad and far more meaningful before one even

realizes. His poem, “ABECEDARIUM APOLOGY,” is magnificent, and might just have

to be heard to be believed, and his “SONNET” has an enormous amount that

happens in a very small space. Ross’ playful engagements with poetic forms

often brings a fresh take on what so many others have previously done, twisting

a variety of expectations around and away. In many ways, Stuart Ross might just

be one of the most published of Canada’s underrated poets. Why does humour get

such a bad rap?

SONNET

Bye Bye Birdie.

Going Down the Road.

The Ticket That

Exploded.

Al Purdy.

Felix the Cat.

Dennis Kucinich.

A Day in the Life of

Ivan Denisovich.

Doctor Rat.

Welcome to the Monkey

House.

Evelyn Lau.

I Can See Clearly Now.

Mickey Mouse.

Jack and the Beanstalk.

Talk Talk.

[Marthe Reed, tabling] Grand Rapids MI: Having

recently moved from Lafayette, Louisiana to Syracuse New York, we were able to

engage with a variety of American poet Marthe Reed’s publishing enterprises,

including her new chapbook, ROOMS

(Shirt Pocket Press, 2014). A collection of seven short poems, each exist as a

kind of point-form sketch of a different room, perhaps in the house they left

behind in Lafayette, which by itself suggests an interesting artifact on their

prior space. As bpNichol explored the body through his Selected Organs (Black Moss Press, 1988), a sequence later

published in full as Organ Music (Black

Moss Press, 2012), so too does Reed explore the body of a house, but reduced,

sketched, and down to the bare essentials.

Bed

broadside

bark abstraction

flamingo encyclopedia

poem

poem

folded enameled copper

oils on wood

alpaca alpaca

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)