AFTER HISTORY

Has anyone managed to

make a world.

after race we turn to genetics,

return

after to the archives for

new history. Who

then determines when we’re

from. Roots,

we learn to speak of

them. The baobabs do

not speak of themselves. We

hear wind flee

through their leaves. We see

our minds feast

through bark as ants

warring with termites.

Has anyone managed to

make themselves.

We wonder our excitement

when we see

only our wide teeth

speak, only our large lips,

anything so small as

proof that we could not

hold one another. We do

maybe. We did not.

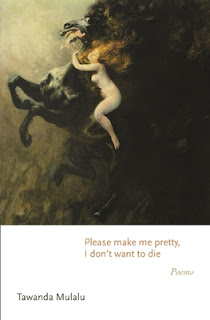

I was startled by the poems in New York City-based poet Tawanda Mulalu’s full-length debut, his Please make me pretty, I don’t want to die: Poems (Princeton University Press, 2022). There is such a smart and vibrant energy and confidence to this collection, composed through a thick, complicated series of wisdoms, descriptions and lyric offerings. “So,” he writes, as part of the poem “STILL LIFE,” “I’m part of this thing where fish learned to walk. / Your first baby pictures look like seahorses. / We stop now to consider our lungs. / Look at all that we have made / and behold it is very good.” Referencing his debut, then still in-progress, as part of a short write-up on the Tin House website, he offers that:

The poems within it seem

(to me) to be about the failure of intimacy and frequently ask what it means to

be (or not be) seen by others and by oneself. They are written from, for and

against: America, blackness, Sylvia Plath, prettiness, song, poetry, and mind.

In many ways, Mulalu offers his collection as one structured two-fold: an engagement with form, and an articulation and examination of placement and positioning, each thread an essential way through which an engagement with the other is achieved. Mulalu writes through the form of the elegy and the sonnet, for example, offering a lyric as much music as it might be a kind of dream; as much sadness and grief as he includes a kind of dreamy optimism. Across a wide scope of attention, Mulalu writes of the difficulty of families, traditional poetic forms and ecological concerns; he writes of racism and America; he writes of difference and division, citing aggressions and encounters that exhaust, but offered in a way that enlightens as much as documents. As he writes to close the poem “SECOND SONNET”: “There is too much potential in this dying / planet not to believe you are at the end of this. yes even I / hear you long enough to hear another person: and think she / was as clever as you said you were at the start of this: who / is not the point. I meant this Earth.” One can’t help but admire the seemingly straight lines, lyric ease and accumulations of Mulalu’s poems, composing lines that bend in the light, or perhaps even with gravity, given their incredible density and strength. These are highly structured poems that read with such a lightness of line that one might get lost. There’s so much happening in these poems, so much spoken and hinted, such as the poem “MY SISTER LIKES GIRLS AND DOES NOT / RETURN FOR MY MOTHER’S FIFTIETH,” a poem that begins: “Months after I hadn’t had my first oyster / before I came to America. My sister in Canada now // where it starts snowing soon. Things I haven’t seen / keep cropping up. Movies are colonialism // and I’m such a dutiful director, swerving cameras / around oceans I hadn’t had before.” Mulalu’s poems point to song, but a song that carries the enormous weight and heft of love and loss and being, articulating clever turns of narrative and turns of phrase, showcasing some of the best the lyric form might offer across a canvas as wide as it is precise. “My open window / a synecdoche of country.” he writes, as part of the poem “MISCEGENATION ELEGY,” “No matter how much smoke a pig / roasts won’t erupt into song.”

No comments:

Post a Comment