First Date

You bought a plot of land

and you dug a hole. You filled the hole with seasoned meat and cedar and silk. You

covered the hole and you waited. It was supposed to take nine months, but I arrived

in seven. When I appeared I was grown and vocal. You held me like a science finalist.

The floor plan was stamped to my chest.

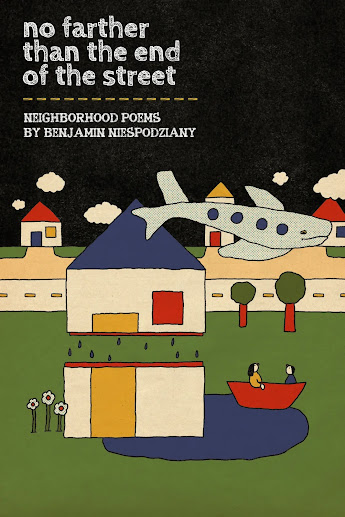

The full-length debut by Chicago poet Benjamin Niespodziany, following chapbooks through above/ground press and Dark Hour Books, is no farther than the end of the street (Los Angeles CA: Okay Donkey Press, 2022), a collection predominantly constructed out of short, single-stanza prose poems that float the realm between lyric, short story and lullaby. “I wrote you a poem,” he writes, to open the poem “Publicity Stunt,” “called ‘Planet Earth.’ / It’s a ghost / poem or maybe a poem // I ghost wrote. It’s an / X-ray I pass around / the neighborhood.” Holding echoes of myth and fable, Niespodziany’s poems offer a selection of prose openings into whole worlds that might even exist between the curved narratives of Lydia Davis and the surrealisms of Stuart Ross. “You can’t / take my call.” he writes, to open the poem “The Silence That Finds Us,” “You’re busy // making volcanoes / out of swamp products // and ketchup packets.”

Organized across five numbered sections—“Yardmouth,” “Baffling Scaffolding,” “The Flimsy Chimney,” “Front Lawn Songs” and “Partial Architectures”—there is such a sense of whimsy and narrative play throughout these poems, writing magical elements of hearts lost and ghosts on the tongue, blended in and around direct statements. “With a pitcher of water,” he writes, to open the poem “In Our Backyard Garden,” “I stood next to a neighbor / who had dying flowers for a face.” He writes a lyric minimalism of layering and accumulation, one that understands both pause and pivot, narrative structures and a scaffolding deliberately playing with what to suggest, what to exclude and what to offer directly. He evokes small lyric scenes, crafting realities built out of concrete and smoke. “We could no longer afford our gardener.” he writes, to open the prose poem “The Harmless Gardener.” “I asked / him over to talk. He arrived hanging onto his / cane. I looked and his cane became a sword. I / looked again, his sword was a mailbox. The flag / was raised.”

There is such a delight to these pieces, and there are moments throughout this collection that I almost see echoes of the short stories of Richard Brautigan, offering insights into daily interactions and simply being and living in and moving through the world, tinged with a wistful surrealism simultaneously playful and dark, moving in, out and through focus, from sentence to sentence. there is such a delight, even across such dark foundations of loss, death and distance, as connections are established, demolished or never quite connect. Across eighty-four poems, Niespodziany writes of first dates, first loves, weddings, streetscapes and neighbours, suggesting a lyric set entirely within the focus of a small geography, even one centred on the domestic, with not one poem set beyond a boundary set just down Niespodziany’s imaginary or actual street. One imagines a cul-de-sac, just down from an urban setting of shops and what-have-you; a small tucked-aside corner of residencial space, not far from everything else in the world. One imagines a set of boundaries established to attempt to keep the narrator and his household safe, from whatever dangers might exist beyond.

Neighbor

You witnessed her death on our street. Your feet were in the street, but your body was in the lawn. I was inside our home, crouched like a cloud. “Now he’s a widow,” you said, pointing to the grieving husband across the street as he sleepily watched his wife being carted away. The next day, we went to the funeral in their backyard. Everyone was there, even the dead wife. She was floating over her coffin like some type of goblin we wanted to trust. An antelope leaned against their fence. After the funeral, authorities ended up taking your mug shot. Now you cough without a bonnet. Now you claw at the attic’s moon. Too soon, the body was gone and we were back to talking about lawn darts and starter homes. I was alone. You were alone. We held hands.

As part of his statement on the prose poem, included in a folio on the contemporary prose poem at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics, Niespodziany wrote: “The prose poem does not demand an ending. It does not demand an explanation. It does not need a resolution. It contains none of these things and all of these things. Anything can happen inside of such a boxed-in paragraph. A pair of wings catches fire and turns into a frog. I fell in love with the prose poem because it felt like a contained commercial break, a parable in interlude form. Enough to chew on while eating lunch, while walking around the neighborhood. A world within a wink.”

No comments:

Post a Comment