In 1992, my older brother

had his first life-threatening seizure. My mother tells me I was on the living

room floor playing with a toy ambulance, manically opening and shutting the

doors. It was in the afternoon. It was in Dover, Vermont. It was possibly

summer. They left me with the neighbors. We’re going to have a real good

time, the neighbors said. We have some roast beef to feed you. I remember

the car moving down the long driveway, entering the dark wood, crossing the

edge of what I knew. (“PROLOGUE”)

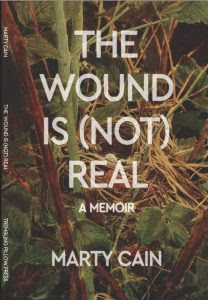

I’ve been waiting a while to see the finished version of Ithica, New York writer and publisher Marty Cain’s full-length The Wound is (Not) Real: A Memoir (New Orleans LA: Trembling Pillow Press, 2022), after having caught excerpts of the work-in-progress through his chapbook Four Essays (Tammy Journal, 2019) [see my review of such here]. The Wound is (Not) Real: A Memoir is composed as a lyric examination of memory and trauma, set as sectioned prose poem sections that move in and out of surreal imagery, nearly as a kind of long poem reminiscent of the accumulated short sections of Rosmarie and Keith Waldrop’s collaborative memoir-dos-a-dos Cesi nest pas Keith / Cesi n’est pas Rosmarie (Burning Deck, 2002), or even Aditi Machado’s remarkable chapbook-length lyric essay on form, The End (Brooklyn NY: Ugly Duckling Presse, 2020) [see my review of such here].

Opening with his first memory of his brother’s seizures, Cain unfolds the collection as a book of brothers, violence, illness, abuse, sex, memory and self-discovery. “My destruction,” he writes early on in the collection, “I take it with me. I breathe in whole numbers. I breathe in a dream with a gun to my head, and upon my waking, I stand in the shower and kneel in the stream; a field of flowers, the allergens enter, I expectorate softly with my mouth to the drain, I suck in hairs, I suck in piss, I suck in fear that fills my body like an egg and when I slice my arm the yolk comes running. I need a pill. I need a pill for my frantic intestines.” He writes of trauma, and of memory, offering a portrait that occasionally slips out of focus; sometimes necessarily so. This is a powerful collection, one that works to critique and unpack as much as possible, swirling through commentary on poems by Wordsworth and Robert Penn Warren against his own emergence into literary creation and literary thinking. Simultaneously meditative and urgent, Cain slips in and around form as well, blending literary criticism with trauma memoir, critical document and coming out story, providing articulate and comprehensive arguments made through accumulation around both form and survival. “And form is a feeling.” he writes, as part of “WORDSWORTH POEM.” “And form is a garment.” Or, as he writes as part of the extended “ROBERT PENN WARREN POEM”:

Describe your poetic lineage, the white male professor says. This is my first poem about my father.

/

When I consider Warren’s

relationship with Time, I often think of his desire to step outside it—to hover

above it like film on milk, like a membrane of fog on a pasture… To give the

illusion of relinquishing control, but in actuality, wielding it

authoritatively—as if to say, I can step outside this poem, BECAUSE I OWN

IT, I can survey this Arcadian field from afar, BECAUSE I OWN IT. I can conceal

process, blood and bodies, BECAUSE I AM A GOD. I am a white man who owns Time.

this is for me, and I WILL LIVE FOREVER.

No comments:

Post a Comment