Heather Campbell has spent over 30 years in communications and freelance writing, specializing in issues relevant to Northern Ontario communities. A graduate of York University (BA Sociology ’92), she has combined her education, experience and ‘need to initiate’ by starting a local chapter of the Professional Writers Association of Canada and the Wordstock Sudbury Literary Festival. She has held the position of Chair for LitDistCo, a small book distribution collective of literary book publishers, since February 2020 and she is a Board member of the Ontario Book Publishers Organization.

Latitude 46 is a member of Literary Press Group, Ontario Book Publishers Organization, Association of Canadian Publishers and eBOUND. We receive funding from Ontario Arts Council, Canada Council of the Arts, Ontario Media Development Corporation and Canada Book Fund.

1.When did Latitude46 first start? How have your original goals as a publisher shifted since you started, if at all? And what have you learned through the process?

We started on March 31, 2015 and published our first anthology, Along the 46th: Short Fiction in November 2015.

Latitude 46 was started by myself and Laura Stradiotto, a fellow freelance journalist, who agreed that we wanted to ensure Northern Ontario continued to have a publishing house after Scrivener Press closed. Our mandate to publish Northern Ontario authors and stories has not changed. We receive approximately 50-60 submissions each year (increasing every year), plus I seek out diverse authors.

Laura left to pursue other interests in 2019 but remains supportive of the press. Our consulting editor Mitchell Gauvin now Dr. Mitchell Gauvin (English), also a published author (Vandal Confessions) continues to work with us.

I initially approached the owner of Scrivener Press to purchase from him, however, his response was “the learning curve is too much” which I took as patriarchal at the time. It has been an enormous learning curve indeed but certainly achievable. I have had many mentors including Leigh Nash, Karl Seigler, Hazel and Jay Millar and many professional development opportunities. I am never not learning about different aspects of publishing. Currently I am diving into exporting and foreign rights.

2 – What first brought you to publishing?

I spent the first 30 years of my life in Toronto before moving to Sudbury. When I was 19 years old I loved reading and had a dream of becoming a novelist. After finishing high school I met with a counsellor at Centennial College to explore the Book Design and Production program, however, I also was interested in university and was exploring social work. I decided on sociology with a minor in English at York University. The next 30 years I spent my career in communications and writing (freelance journalism). At 50, my kids were gone to university and Scrivener Press was closing. I had some experience ghostwriting and self-publishing for others so I understood a bit about making books. Before I started the press though, I met with ACP Executive Director, Denise Truax of Prise de parole (Francophone publisher in Sudbury) and Laurence Steven, retiring publisher of Scrivener Press to get their perspective on starting a brand new press. Based on what we learned, we then decided to climb this mountain.

3 – What do you consider the role and responsibilities, if any, of small publishing?

Small press, Indie publishing, is here to ensure that all voices are heard, particularly those who are overlooked because they don’t meet the criteria for selling enough copies to support a corporation. Indie publishing spends a great deal of time nurturing emerging authors, or at least I do! I am so impressed by the books being published by my fellow indie presses. Books that have the power to inform, inspire and tell the truth. We are focused on storytelling by Canadians for the whole world to read.

As a small press in Northern Ontario, where many authors are distanced from the “publishing industry”, I invest a great deal of time to answering questions, encourage young authors, and raising the bar on quality of writing. I also started Wordstock Sudbury Literary Festival in 2013 and we are presenting our 9th edition this year. I have such a passion for writing and books and wanting others to have access to the industry. I always bring professionals from the industry, award winning authors as well as local authors to the festival.

4 – What do you see your press doing that no one else is?

We are a regional press. It limits us in some ways, but at the same time creates a clear focus. We are the only English language trade publisher in Northern Ontario. For Ontario in particular, Northern Ontario is often overlooked. However, the culture and stories that reside here are connected to the land and unique experiences. I am not sure if other small presses find this but having a publisher who is accessible means I get a lot of people contacting me, approaching me at events to ask questions about publishing or pitch me directly. I am not able to hide in an office tower in a big city, or away from view in a rural location. I feel a certain responsibility, as a community member, to help in some way whether directing to a more appropriate publisher ie children’s, more writing assistance or even self-publishing.

5 – What do you see as the most effective way to get new books out into the world?

Interesting question as the world around us is “pivoting”. If this is a distribution question, lots could be done. We need to have the return of local independent bookstores. I have very recently been getting involved in the conversation between booksellers and publishers and so much can be done in this relationship that would move books better. My experience with the festival has shown me that readers love meeting and hearing from writers. They immediately go buy the books. Book clubs and video chats move books. In terms of marketing to move books, we have relied on social media and the digital environment but we are finding out that we have so little control over who actually sees those messages. I am also behind advocating for more Canadian books in Canadian schools.

6 – How involved an editor are you? Do you dig deep into line edits, or do you prefer more of a light touch?

The most editing I do as the publisher is a light touch to start and then hand over to an editor who can dig deep. We hire editors based on the book and author. For example, we just published Aurore Gatwenzi’s debut poetry collection, Gold Pours this past fall and she really wanted to work with Britta Badour. We had Britta at Wordstock Sudbury Literary Festival so we hired her to work with Aurore. I love that! Not only great editing but great mentorship too. Mitchell Gauvin will work on the majority and he is such a thoughtful and thorough editor. I also meet with each author I sign prior to signing and we have the discussion about their approach to editing. I need to see that they are keen and willing for a good edit.

7 – How do your books get distributed? What are your usual print runs?

Our books are distributed by LitDistCo and I have held the role of Chair for LitDistCo since February 2020. I also do a good number of sales from our online shop.

I have been keeping our print runs low since initially printing 500 – 1,000 on early books only to have them sitting in my shed :<( We have been printing with Rapido Books and they have a program where each print run on a single title adjusts unit price to reflect the total amount run. (Hope that makes sense). I will typically run 350-400 to start, and go up from there depending on demand.

8 – How many other people are involved with editing or production? Do you work with other editors, and if so, how effective do you find it? What are the benefits, drawbacks?

As mentioned before we hire editors based on author and book. I am currently working with Sarah Jarvis for our first YA Novel. I have hired Nathan Adler as a sensitivity reader. I hire local proofreaders.

We started with hiring a designer but I eventually learned to design because it was frustrating to wait for them to get to a small edit or rushing through a design.

I like hiring by book. I think we do well for the author and the story when we have an interested team working on the book. I have purchased local art for covers as well.

The only drawback I have encountered is timing on design work. There is an immense amount of administrative work to publishing and I find myself leaving the layout or design to the last minute.

9– How has being an editor/publisher changed the way you think about your own writing?

When I initially started the press and read through submissions it made me want to write again. Over time, I am much too busy to even think about writing! I just read Linda Leith’s memoir and welcomed her to Sudbury for the Wordstock Sudbury Literary Festival, we have some similarities in establishing a literary festival and publishing house. I find her writing beautiful and maybe someday I will write a beautiful memoir too.

10– How do you approach the idea of publishing your own writing? Some, such as Gary Geddes when he still ran Cormorant, refused such, yet various Coach House Press’ editors had titles during their tenures as editors for the press, including Victor Coleman and bpNichol. What do you think of the arguments for or against, or do you see the whole question as irrelevant?

I won’t publish my own writing at this point. For me, I don’t have time but I would likely do what Linda Leith did and find another publisher. I do believe there needs to be some objectivity to creating and promoting your work. If I published under Latitude 46, it would feel more like self-publishing.

11– How do you see Latitude46 evolving?

My dream for Latitude 46 is to have a long life – another 20 years and hopefully sell so it can live on after me. I hope we uncover some talented and impactful authors who provoke conversations. We are working on exporting more books into the US, but I also hope we can negotiate more foreign translation rights for our authors and attend book fairs around the world.

It has been an immense amount of time and work to reach where we are now. I decided in the beginning that we would make our mistakes in the early years but hone our craft of publishing in subsequent years. We are honing the publishing process now in order to reach that dream.

Building a committed and solid team is also important for longevity.

12– What, as a publisher, are you most proud of accomplishing? What do you think people have overlooked about your publications? What is your biggest frustration?

The fact that we are still here after 2020 is such an accomplishment! That was a tough year. We were in operation for only 5 years when the pandemic hit.

I sometimes feel the industry wants Latitude 46 to prove itself, will it last? will they publish “literary” work? It has been a tough slog to get media attention on our books yet The Miramichi Reader has awarded recognition to our books a few times and we have received Northern Ontario Literary Awards. We published Danielle Daniel’s memoir and she eventually was picked up by Harper Collins. We have supported Rod Carley (A Matter of Will and Kinmount) who was longlisted for the Stephen Leacock Award. We have released 31 titles in 7 years and on a shoestring budget. I have yet to pay myself as well.

I have also given back to the industry by Chairing LitDistCo through challenging times and sitting on the Ontario Book Publishers Organization board.

My biggest frustration is that I am doing all the right things to build a publishing house from the ground up yet struggle for my authors to get any national attention. I am so grateful to be working with Nathaniel Moore who has been able to move some media to consider what we are doing in Northern Ontario.

13– Who were your early publishing models when starting out?

I am so grateful for making a connection with Jay and Hazel Millar in our second year of opening the business and watched them handle their publishing house name change. Was so impressed with their handling of the situation. Jay had said to me once, “Every week we make a toast we are still here this week!”. It let me know that our experiences were as they should be for starting out. We may never reach “midsize house” but I do watch House of Anansi and ECW. David Caron has always been encouraging with me and I love their innovative and progressive approach to business. What I love about publishing is how supportive most publishers are to each other.

14– How does Latitude46 work to engage with your immediate literary community, and community at large? What journals or presses do you see Latitude46 in dialogue with? How important do you see those dialogues, those conversations?

As mentioned earlier I am the founder and Festival Director for Wordstock Sudbury Literary Festival, and in both of these roles I strive to influence the literary arts community to work collaboratively to support and encourage writers to live and work in Northern Ontario.

I have not had the opportunity to connect much with journals but have a few of my favourites such as subTerrain.

I attend all the ACP, LPG and OBPO meetings to connect with other presses and contribute to conversations about industry challenges from funding, supply chain and marketing. I love that kind of work where we are moving the industry forward yet always keeping our values intact. To me it’s not just about the physical book but the voices, ideas and intellectual contributions from so many voices that we are ensuring have airtime.

15– Do you hold regular or occasional readings or launches? How important do you see public readings and other events?

Prior to Covid we held in-person launches to celebrate. In 2017 when we launched our 5 fall books, we welcomed 200 people to an in-person event. I believe that public readings are vital to the scope of reading and writing. Having a conversation about what we are reading is important to readers, and writers. It also makes an enormous difference to have author signings. We do not have a local independent bookseller in Sudbury, we do have a Chapters store though.

My perk as festival director is when I have programmed a diverse lineup of authors and they engage in a thoughtful conversation both among themselves and with contributions from the audience. I love watching the audience come out and give me feedback on the session with beaming faces and exclamations of “that blew my mind”, that is why I do this!

The festival has also held a regular Poetry Slam (I am fond of this genre) and have found a few poets through this community event. I do attend readings and Open Mics to be aware of what’s happening with local authors as well.

16– How do you utilize the internet, if at all, to further your goals?

I like to think we have a good presence online – website, social media (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, LinkedIn), YouTube and news items – we also have an online bookshop which are all accessible online.

17– Do you take submissions? If so, what aren’t you looking for?

We have always had an open submission. Our submission guidelines can be found on our website. I would really love to receive more diverse voices stepping forward. Our mandate is to publish Northern Ontario authors and stories about Northern Ontario. We publish literary fiction, non fiction, poetry and YA.

We do not publish children’s literature, fantasy, genre fiction. I am drawn to smart, provocative and unique stories.

18– Tell me about three of your most recent titles, and why they’re special.

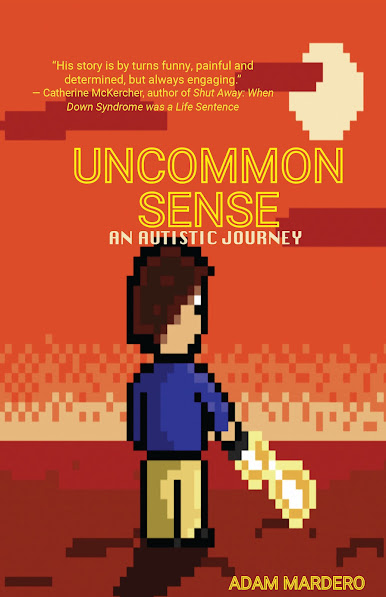

Our Fall 2021 titles are two of my favourite. Adam Mardero’s Uncommon Sense: An Autistic Journey. Adam shares how he navigated the darkest dungeons and brightest triumphs of life on the Autistic Spectrum and through it all discovers the ultimate treasure: what it really means to find yourself and live life on your own terms. He has an incredibly generous personality. I met Adam in 2015 at a community event. We were standing beside each other and he introduced himself, not knowing I was a publisher. Through our conversation he shared that he was thinking of writing about his experience with Asperger’s. We encouraged and guided Adam for the next several years until he had a manuscript ready for publication. I am thrilled with the end result.

Aurore Gatwenzi is a young Black poet who is born and raised in Sudbury by Burundi immigrants. Her debut poetry collection is called Gold Pours. She talks about God, identity, heartbreak and passion. She has an honest approach to writing that exposes readers to humility, surrender and lessons learned from courageous acts of vulnerability. I met Aurore when she performed her poetry at a festival poetry slam. She is also an aspiring actor.

We are publishing another emerging Northern Ontario poet, Noelle Schmidt with her debut collection Claimings and Other Wild Things in April 2022. She is a young queer, non-binary poet and sheds light on growing up in Northern Ontario but also about her German heritage. She has some impressive blurbs. Noelle approached us in 2018 to complete her university placement with us and later submitted her manuscript.

These three emerging writers with diverse perspectives shed light on growing up and finding their authentic selves despite the distance from a large urban centre and limited diversity.