I am afraid of being a

light-year

because I fear what lies

in the dark.

I fear the dark, because

it can be so easy to lie.

For instance: when I said

I needed some space,

I hoped you would’ve read

the space

between my breath as a

cry for more attention.

(“An Argument about Being Needy while / Underneath Binary

Stars”)

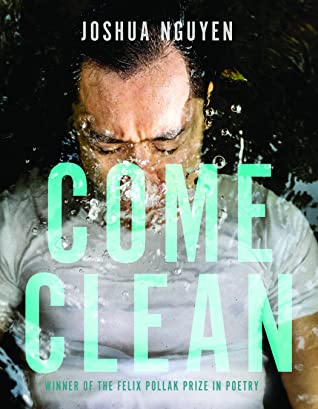

Winner of the Felix Pollak Prize in Poetry, is Vietnamese American writer Joshua Nguyen’s full-length debut, Come Clean (Madison WI: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2021), a collection that, according to the cover copy, “compartmentalizes past trauma—sexual and generational—through the quotidian. Poems confront the speaker’s past by physically—and mentally—cleaning up. Here, the Asian American masculine interrogates the domestic space through the sensual and finds healing through family and in everyday rhythms: rinsing rice until the water runs clear, folding clean shirts, and re-creating an unwritten family recipe.” The poems of Nguyen’s Come Clean exist as an accumulative memoir of trauma and growing up, writing via a variety of poetic forms (including haibun, which is always good to see), something reminiscent of Diane Seuss’ recent frank: sonnets (Minneapolis MN: Graywolf Press, 2021) [see my review of such here], a collection that also explored the accumulative poetic memoir via poetic form (hers being, for that particular project, exclusively the sonnet). Nguyen writes on culture, conflict, abuse, sexuality and masculinity, and to a younger brother, composing poems that are self-effacing and embracing failure, even while examining trauma and the ways in which one can unpack, and move beyond. As the poem “A Failed American Lục Bát Responds” asks: “Can I be read from / fathers who don’t speak, who find love / in Vietnamese fantasy, / in warriors trying to find their way home? / O monosyllabic birthplace, / can I self-colonize myself, / be the fusion the world doesn’t want to see?” These poems are emotionally raw, performative and lyrically sharp, carefully crafted to embrace a lyric that punctuates and punches without holding back.

As much an underpinning examining trauma, there is a tenderness that comes through the lyric as well, such as the second stanza of “American Lục Bát for Peeling Eggs,” that reads: “Love, you are old / enough now to unfold the skin / back on these white shells.” Or the opening lines of “March 4th,” set at the opening of the collection:

Tell the priest to wait outside the hospital room.

I am wiping the blood of his handsome head.

My son must be presentable to the world.

My son, the world will try to bury you.

No comments:

Post a Comment