My review of CAConrad's Amanda Paradise: Resurrect Extinct Vibrations (Wave Books, 2021), recently appeared online at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics.

Monday, February 28, 2022

Sunday, February 27, 2022

R. Kolewe, The Absence of Zero

My review of Toronto poet R. Kolewe's third full-length poetry title, The Absence of Zero (Toronto ON: Book*hug Press, 2021), recently appeared online at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics.

Saturday, February 26, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Charlie Petch

Charlie Petch (they/them, he/him) is a disabled/queer/transmasculine multidisciplinary artist who resides in Tkaronto/Toronto. A poet, playwright, librettist, musician, lighting designer, and host, Petch was the 2017 Poet of Honour for SpeakNorth national festival, winner of the Golden Beret lifetime achievement in spoken word with The League of Canadian Poets (2020), and founder of Hot Damn it's a Queer Slam. Petch is a touring performer, as well as a mentor and workshop facilitator. In 2021, they launched Daughter of Geppetto, a multimedia/dance/music/performance poetry piece with Wind in the Leaves (TBA), their first full length poetry collection Why I Was Late in Sept with Brick Books, and their libretto Medusa's Children with Opera QTO.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book was one that was a collection of my photographs I’d taken of my band “The Silverhearts” from 2007 to 2009. It came out when we were on a western tour. After the trip, they left a voicemail saying they didn’t need a saw player if there’s already a Theremin player. Personally I thought we needed less guitar players. They disagreed so I have a lot of those books left. Now I’m a one person show, replaced the band with a loop pedal and now everyone listens to my great ideas. I’m happy my next full book is one I don’t semi quietly resent. Rather, it’s a celebration and a mild anxiety, because, wow, some people are going to read it, and it’s personal, you know?

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I actually started writing mystery stories as an 8 year old. My lateral lisp (which I’ve since done years of speech therapy to correct) meant that my friends were all books, or imaginary. I got that fab new pen that had 4 different pen colours in it, and used a different colour for each character. Later I realized, I just loved dialogue and I went to playwriting. I started writing poetry when I was a teenager, and my first book was created in my early 20’s as a companion piece to an anti-valentine’s night I hosted as my alter ego – Tits McGee, it was called You Make Me Sick – The love poems of Tits McGee. I wrote three more chapbooks as her (that were each tied to hosting events), until I started really write in my own voice. When I found the poetry slam, my playwright heart just leapt. The monologue series of my dreams.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

My writing has always come quickly, I have that ADD brain so it’s just full of words rearranging itself and getting everywhere. I’ve really committed to having deep and careful process, since my mind loves to rush to the finish line. Ever since I did the Spoken Word & Music stint at Banff, I’ve tried to re-create the music hut, and the pin board freedom. So now my books and plays become a kind of wall sculpture of notes hung on twine attached to wire, and little objects the bring life to the whole thing. Some things will take me a day, some will take me 5 years to get right. It really depends on the subject and if there’s growth in the characters that happen because of them, or internally in myself.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Sometimes there’s a tangible spark of an idea, a line that wants more words that I keep in a notebook, or some mornings I’ll just open up a book and point to a page and see if that’s a good prompt for the day. My spoken word theatre shows are something I really put together heavily with a concept and keep in that atmosphere to create, with no real thought of the ending until it shows itself. I think the project really shows itself to me and tells me the medium it would be happiest in and I listen, plan, adjust, or just write for 10 mins to keep up practice and see if I can get a sweet poem that can sit a bit before editing. For this book, I really just put together all my writing since 2014 and my editors found the book inside the manuscript. My next manuscript will have a tight theme and it’s currently a kind of installation project on my wall.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Honestly if you see me not on a stage, I’m quietly waiting to be onstage. I adore performing and being on tour, there is no more content me than when I am in front of an audience. I also love to teach others the craft of public readings, whether they are reading off page or performing memorized work. The more tools you can feel in control of , the better the show. I want everyone to excel and feel confident, I love a good poetry reading.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I am always trying to be aware of language, of my own internalized racism, ableism, misogyny etc., when writing, because I often skirt the line to get points across. I also place myself as a white settler in my work, and consider my audience is not all also this background. I strive to deeply recognize my own position and privilege as a white trans and non-binary person with an invisible disability. I aim to speak to issues of colonization, not only because it hid our genders, but also what it’s done to us all as a society trying to co-exist in a world on fire. I try to not speak over top of anyone, or consider myself someone who speaks on behalf of my immediate community, or any community that is not mine. I strive to find the right words to also platform other’s ideals forward in gestures of solidarity, with credit paid.

Current questions for me are always – What am I cultivating with my work? How do I make it more accessible? How do I make the audience care about something they may not relate to?

I find satire and humour to be such an excellent tool for accessibility, and message parachuting. I try to almost convert audiences into caring about things they likely would never want to address or think about; to do this in a way that feels both embracing and respectful to others who share these obstacles. Just writing about disability is such a trip. How do you get someone to understand something they never have to personally care about something they can’t see or experience. How do you make them believe that ableism affects us all? It’s a constant riddle I try to solve. I once performed a poem about gender at an event in Michigan in 2016 when Tr*mp was running. I was so scared to do it but I know at least one person in the audience decided to change their vote after hearing it. These are the poems I want to put out into the world.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

The best poets are the ones who tell the truth, no matter the cost. The ones who are future thinkers and speakers of our difficult histories. I know Socrates was a creepy dude but I remember reading Plato’s Republic and thinking, heck yeah poets should be in positions of power. We all need the truth so bad in order to save the planet, to confront who we are, what we’ve done, and how to work in solidarity with everyone. I really believe our leaders should be spoken word artists, should be 2 Spirit people, how can we even meet climate needs without that level of land experience? We need decolonization, and I see poets in particular, speaking up about all of this. Leadership needs vision, creativity and most of all, the truth. We are living in radical times and poets and indigenous people are on the front lines of these conversations.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Honestly, I loved it. I was gifted so well by Brick Books to have two editors, Nick Thran and Andrea Thompson. Andrea, as we should all know, is one of the originals in spoken word poetry in Toronto and is just wonderful to work with. Nick is an incredible page poet, so he excelled in the edits for the page, and Andrea ensured the sound, pace and presence of the spoken word voice was preserved, as well as did page edits. I was super spoiled and they really reassured me that I had the final decisions around how my work was presented. The final round of copy edits with Alayna Munce really cemented how I want my style to be represented on the page going forward. I’m super excited to know my style thanks to the lenses of such experts as these three.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

My high school drama teacher ordered us to never argue with critique or say anything in our defence. He told us to simply listen to feedback, the person critiquing you is like a professional audience member. You know your work best, so take what you need from them, leave the rest, never argue, and always thank them. It absolutely translates to any moment of critique.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to plays to performance to librettos)? What do you see as the appeal?

I am a lover of atmosphere, so being able to add atmosphere to any work, whether that is in collaboration, or in my own multimedia creation, I just adore being able to present the work in the way I want the audience to experience it. When I worked primarily in theatre, I learned how to do everything so that I could know what to expect and how to achieve it. I find it very easy and natural to move from one genre to the next. Again, thanking my ADD brain for this, because how amazing is it to launch a book, a workshop play, a filmed libretto, a multimedia show and a book all in one year? I didn’t mean to have it all be at once but the past 1.5 years have moved a lot of performances around. Being multidisciplinary means I never have to be tied to one genre. It feels natural to never fit into a box for very long, to always be shifting. As someone who has learned by doing, it also means I’ve not had academia narrow my scope, or expectation of what poetry, music or theatre should be.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I get up, drink Vega Mix, do a little run (ok it’s more like powerwalking), then put on the kettle and do stretches, physio and weight lifting while listening to ambient music, the gay composer Chopin’s nocturnes, or slow pop ballads. If the dog is with me (I share a sweet hound/lab with a dear friend), we have us a wrestle, then I sit down at the computer and attempt to write something before the day takes my access away from the creative brain.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I just let myself stall for a bit. Sometimes I need a break. Then it will all build up and the panic will start because I am so fed by being in a state of creation, and I put a daily prompt back into my practice to keep flexing my poetry brain muscle. I also have a private group I do first drafts with. I always need a bit of an audience, and sometimes I need a deadline. I’m very motivated to please a deadline and/or an audience.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Vicks VapoRub, doggy paws, old books, wet ravines, sawdust, and horseshit. Really we moved so much that I don’t remember a specific home, only a series of places that we lived in while renovating, but these scents will land me back in time. My dog’s paws are the greatest access I have to childhood memories.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Oh yes, some things I see before I write them. Sometimes I play music for inspiration, sometimes I have the song before the words, and sometimes the story shows itself to me in nature. I’m open to all influences, I have a very vessel approach to existing as an artist in this world. I love imagining what insects care about, what a rock might think about getting sat on, as a lonely bullied kid, I had to make friends out of everything around me and script them into my life, so I know the gift of remaining open and hopeful.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I will always thank Kurt Vonnegut for Breakfast of Champions. When I found it at 13, I truly knew, you don’t have to pay attention to traditional form, linear timelines, or cater to an audiences expectation of what novels or anything should be. I loved that he always looked to the science students to find the writers, and avoided the English students. Later, I got his asshole (drawing from the book) tattooed on my armpit by the drummer from my punk/noise band. He really woke up the artist in me.

James Baldwin opened me up to queer writing, to deep atmosphere and prose novels, as well as some of the best critical race discourse that still serves today. I still love a good Tennessee Williams play with all that sweltering Louisiana flair and queer camp palate. Dorothy Parker is also an influence, her sharp wit and notions that kind of come around the corner and slap you in the face, and gosh I love her handprint on me.

My current obsession is A Black Lady Sketch Show, created by Robin Thede. It really has no boundaries and is always so creative, unexpected and totally genius. Truly, I sit in awe of the level of comedy, and thought that’s in every episode. It’s a show that should be studied, like an entire university course should be dedicated to it. It’s just beyond.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Having worked in film for 8 years doing lighting for everyone else’s scripts, I’d love to do my own or jump into a series and join a writer’s room.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I’ve worked in health care since I was 13, I started with volunteering at Bloorview Children’s surgical rehab centre, working with Occupational Therapists. If I had been a good student, I would have loved to had gotten into that field. Being the child of a nurse, who would hang out in emergency rooms after school, I’ve always loved being in that atmosphere and have worked in hospitals, family health teams, retirement residence, bed allocations and as a 911 operator for ambulance. I sometimes return when I need to make a stable income for a while. But the customer service end of it, the being trans at work end, yeah, I’d rather one on one occupational therapy.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I don’t think I do write as opposed to doing something else. More, I feel like I am always holding a series of spinning plates of freelance, and other disciplines. The only thing I don’t feel I can do is relax, and math.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I am still not over how much I enjoyed Gutter Child by Jael Richardson, just everything I could hope for in such an suspenseful and accessibly written book. The last great film I watched, Disclosure, it’s so important to me that everyone watch this documentary on trans people in culture. So many revelations, including finding out an actress I worked with for year (and truly had hysterical laughter with) is a trans woman. I can’t imagine her coming onto set every day with that fear, and all us burly guys, and endure some of the things they’d freely say around set. Also big on Crip Camp (disability pride and revolutionary history) and The Octopus Teacher just was everything my little kid heart needed to see. Oh geez I’m crying at the computer thinking about it rob.. ack. I guess I’m all about documentaries these days.

20 - What are you currently working on?

Currently I’m working on my Winnebago a Go Go Book tour schedule out west (though that’s super hopeful given the news each day) with the wonderful washboard player Danielle Workman (watch out for our band “Washboard Abs” haha). I’m also working on my next manuscript “Poetic Monologues”, and developing my next play “No one’s special at the hot dog cart” – which is basically – everything I needed to know about working in emergency health care, I learned as a teenage hot dog vendor in downtown Toronto”. Part spoken word play, part de-escalation technique workshop that will be developed with Theatre Passe Muraille’s “The Buzz” workshop series in the new year. I’m also preparing to revamp my multimedia/dance collaborative play Daughter of Geppetto with Citadel Theatre and the Wind in the Leaves collective in the winter. Oh yes, and preparing for Top Surgery after a long and very pandemic related delay of around 3 years since I started the process.

In short, I’m working on keeping the plates all spinning still.

Friday, February 25, 2022

new from above/ground press: G U E S T [a journal of guest editors] #21 : guest-edited by Micah Ballard and Garrett Caples

NOW AVAILABLE: G U E S T #21

produced also as CASTLE GRAYSKULL 1.5

directed by Skeletor

edited by Micah Ballard and Garrett Caples

see here for Micah Ballard and Garrett Caples’ introduction and biographies

featuring new work by:

Colter

Jacobsen (as Teela)

Anne

Waldman

Brian

Lucas

Carrie

Hunter

Roberto

Harrison

Neeli

Cherkovski

Raymond

Foye and Bob Flanagan

Tatiana

Luboviski-Acosta

Tamas

Panitz

Gregory

Corso

$5 + postage / + $1 for Canadian orders; + $2 for US; + $6 outside of North America

Author biographies:

Neeli Cherkovski lives in San Francisco and has published many books of poetry and prose. His most recent poetry collection is ABC (Spuyten Duvyil).

Gregory Corso (1930–2002) was a revolutionary poet of the spirit. He was the author of over a dozen books of poetry and one novel, in addition to posthumously published collections of plays, interviews, and correspondence.

Bob Flanagan (1952–1996) was a poet, musician, and performance artist, famous for exploring themes of sado-masochism. He was published by Dennis Cooper’s Little Caesar magazine, David Trinidad’s Sherwood Press, and Hanuman Books.

Raymond Foye is a curator, publisher, writer and editor. He is currently editing the Collected Poems of Rene Ricard.

Roberto Harrison’s most recent book of poetry is Tropical Lung: exi(s)t(s) (Omnidawn, 2021). He was Milwaukee Poet Laureate 2017–2019 and is also a visual artist.

Carrie Hunter received her MFA/MA in the Poetics program at New College of California, was on the editorial board of Black Radish Books, and for 11 years, edited the chapbook press, ypolita press. She has published around 15 chapbooks and has two books out with Black Radish Books, The Incompossible and Orphan Machines, and a third full-length, Vibratory Milieu, out with Nightboat Books. She lives in San Francisco and teaches ESL.

Colter Jacobsen splits his time between Ukiah (Haiku spelled backwards) and Surprise Valley, both in California. Besides being an artist and musician and living with 16 animals (30,016 if you count the bees), he DJs as Coco, once a month for Nomadic Nightcap, KZYX community radio.

Tatiana Luboviski-Acosta is a Nicaragüense Jewish Californian artist and poet. They are the author of The Easy Body (Timeless, Infinite Light) & the forthcoming La Movida (Nightboat Books). Tatiana grew up east of the Los Angeles River, and has lived in the Ramaytush Ohlone village of Yelamu for the past decade.

Brian Lucas’s most recent publications are Lost Comets (Two-Way Mirror Books, 2021) and Eclipse Babel (Impart Ink/Bootstrap Press, 2015). He lives in Oakland, CA where he also paints and makes music under the Old Million Eye moniker.

Tamas Panitz is the author of Toad’s Sanctuary (Ornithopter Press, 2021), and The House of the Devil (Lunar Chandelier Collective, 2020). A book of poems, The Country Passing By, is forthcoming from Model City, as is a book of his interviews with Peter Lamborn Wilson, called Conversazione, from Autonomedia. Tamas Panitz is also a painter, whose paintings and stray poems can be found on instagram, @tamaspanitz.

Anne Waldman: Recent projects include album SCIAMACHY. Levy-Gorvy & Fast Speaking Music (with William Parker, Laurie Anderson, Guru Moe & others) 2020, Goslings to Prophecy with Emma Gomis (Lune, 2021), Perdu Podcast: HAFEZ .2021, I Wanted To Tell You About My Meditations on Jupiter, Fast Speaking Music, Mexico City 2022. The Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics Summer Writing Program at Naropa opening in June 2022. Forthcoming: New Weathers: Poetics from the Naropa Archive, Nightboat 2022 and BARD,KINETIC, Essays, Poems, Memoir, Coffee House Press 2022.

Thursday, February 24, 2022

Rodrigo Toscano, The Charm & The Dread

Coding

The Pandemic is no longer

an external event, rather

it is an interiority in

search of an externality.

The George Floyd protests

are no longer an externality,

they are an internality

seeking an externality.

Both the pandemic and the

protests form a singularity;

the New Event, as a code,

is seeking hosts.

I’m a host, you’re a

host, unshielded and waiting. Isolated,

we’re all watching The Code

do its thing. Symptoms vary.

The latest from New Orleans, Louisiana poet Rodrigo Toscano is The Charm & The Dread (Hudson NY: Fence Books, 2021), a further example of pandemic-era writing landing into print (I’ve been seeing a flurry of such appear on my doorstep, recently). More overtly political on our current era of lockdowns than what I’ve seen so far via the lyric, Toscano’s poems are unflinching, catching the eye and the ear and holding on, responding to a variety of contemporary markers, from politics and the pandemic to social justice, neoliberalism and the rise of white supremacy, globalization and cross-border North American politics. “back to town this town,” he writes, as part of “The Zone,” “your town’s local admin’s / intensely responsive / tempered by Northern Zone / general imperatives / takes the wind out of / tiki torch supremacist / carnivals and ‘anti-racist’ / corporate peddlers in / permanent Westphalian / mode of inclusion into / neoliberal tribalism of / the 1% (actually less) [.[” His is a lyric that includes loops, swirls and echoes, whether through the poem “Brown Lives” or “The Tango,” the second of which writes: “The tango / you can’t / get between / gotta watch / your feet // Again not / inflection point / material / potential / for all // But tango / white/black / checkerboard / dance floor / all over […].” There is such a music to his cadence, and a calm insistence running through his lyric, writing on borders, history and barricades, lines that demarcate, many of which are never fully understood or agreed-upon. As well, there is an echo of shared structural considerations, including an approach to a socially and politically engaged lyric directness, that Toscano shares with Vancouver poet Stephen Collis. He writes not as a polemic, but as a sequence of conversations, concerns and observations, and not allowing language to interfere with argument, as the poem “Barricades” writes:

He’s fond of peppering in

“on this side of the

barricades”

when speaking political

meaning, his critique of

changes at hand

isn’t coming from the right

meaning, don’t purity

spiral

peeps, be stout

allow room for growth

don’t be a gendarme

of

revolution, be a

full actor, unafraid

aware that the barricades

can pop up anywhere

in front and back

Wednesday, February 23, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Mary Fairhurst Breen

Mary Fairhurst Breen grew up in the suburbs of Toronto and raised her kids in an artsy, slightly gritty part of the city. A translator by training, she spent thirty years in the not-for-profit sector, managing small organizations with big social-change mandates. She also launched her own arts business, indulging her passion for hand-making, which was a colossally enjoyable and unprofitable venture. Its demise gave her the time and impetus to write her family history for her daughters. She began to publish autobiographical stories, and wound up with her first book, Any Kind of Luck at All.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Any Kind of Luck at All is my first book. It comes out in October [ed. note: this interview was conducted in mid-2021], so I can only hope that it does what I want it to do, namely to contribute to the destigmatization of mental illness and addiction by telling the stories of my family members in all their complexity. Writing it has already changed me a great deal, because it was only through the long process of retracing my steps on paper that I was able to see patterns, figure out why events transpired as they did, and begin to forge a way forward with more compassion for the many people in my life whose choices seem regrettable, including myself.

2 - How did you come to non-fiction first, as opposed to, say, fiction or poetry?

I’m creative but perhaps not as imaginative as I once was. I’m very practical. So for me, non-fiction makes sense. I have an insatiable curiosity about how other people live, so I love to read biographies and autobiographies (and watch documentaries). I can escape into a novel, but I don’t know if I could write one.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

Forgive the imagery, but the first very raw draft of this book spewed out of me over the course of a week, 7 years ago now. Then it sat and waited for me to be ready to write it properly. It came apart into separate stories, then back together again to form a whole. It went through multiple edits until I thought it might be something, then another overhaul after the most devastating loss of my life changed the narrative and, to some degree, the purpose of making it public.

By contrast, when I write an article for publication, I am fast. I know what I want to say, and so far I have enjoyed a rapid flow of words. I always let the piece sit for a while though, because improvements inevitably come to me at random moments in the days or weeks following the first draft’s completion.

4 - Where does a work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

With this book, I had no idea what I was writing when I began. I only anticipated an audience of my own family members. As I am a (rather old) emerging writer, this is my first published work apart from a few magazine and newspaper articles and a radio essay. My next book, for young readers, has a fairly precise format that I had to think up in order to apply for arts funding.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I guess I’ll find out as pandemic restrictions lift! I always get a lot out of hearing authors read, and I am very fond of storytelling and the spoken word, so I will prepare by reading aloud to myself to identify passages that I think I can “perform” well. I have always enjoyed public speaking, though reading from this book will be emotionally draining because it’s about my life. I think I’ll choose excerpts that my editor calls “chipper.”

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

Because this book is a memoir, and my other published pieces have also been autobiographical, my main concern is honesty. Memory is an exceedingly tricky thing, and I know I can only portray the past as I experienced and remember it, which will not match how others perceived or recall the same events. I always try to make it clear that my position and privilege as a white, formerly middle-class Canadian settler impact every aspect of my life and give me a great deal of protection, regardless of how much pain I may feel. I have resources others do not, and especially in this time of (overdue) reckoning, I think it’s critical to examine what that means.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

The role of the writer has never been as important as it is now, in the information/disinformation age. It may be harder to discern what to read, but it’s vital for a society in such flux and turmoil to have access to intelligent and diverse voices, expressed through every artistic medium. Future generations (hoping there are some) will need today’s writers to reflect and interpret what the hell was going on in the world in the first decades of this millennium.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Let me state unequivocally that I love my editor at Second Story Press. And my experience working with newspaper, magazine and radio editors has been nothing but positive. These are the people who will save you from terrible embarrassment.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

You should stop using the word should when making decisions (my mother). Always leave a party when you’re still having a good time (also my mother). I think this second one applies to a good many relationships, jobs and other endeavours too.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

The next year will present my first opportunity (and obligation) to dedicate time to writing. I am a morning person, and very disciplined (if not a bit rigid), so I look forward to the luxury of writing daily for the first time in my life.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I give it a time out. I walk away from it and let it think about how uncooperative it has been, then come back to it when it’s ready to behave.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

The scent of my mother’s face powder was a comforting fragrance from my original home, and it lingered on her things for a long time after she died. The scent of the homes I have made is fresh baking.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Everything influences my work, from podcasts to theatre to visual art. Stand-up comedy too - I’ve done it and I think it’s an underrated art form. A comedian has to deliver the goods with a minimum of words, and my objective is to do the same.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I read a lot of Canadian books, with a particular focus of late on Indigenous writers. I really appreciate the way Thomas King, Leanne Betasamosake Simpson and Eden Robinson, among many others, slip humour so gracefully and generously into difficult subject matter. It’s what I try to do in my writing, and as my main tactic for staying sane. I am a huge fan of Emma Donoghue, David Chariandy, Zadie Smith, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Barbara Kingsolver… A saving grace of the pandemic was all the extra reading time.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Nearly everything! Cross Canada in an RV, swim with dolphins, visit Iceland. And also smash the patriarchy.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I have a degree in translation but didn’t use it, and I think I might have succeeded as a literary translator. I would have made a good radio producer, perhaps. Instead, I worked most of my life in the nonprofit sector, and am just now, at the age of 58, embarking on a writing career. It may be 4 pm, but there is plenty of day left.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I did something else until I ran out of things to do for money, and then I wrote about that.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Book: How to Pronounce Knife. Film: Nomadland.

19 - What are you currently working on?

I have a picture book coming out this fall with Anchorless Press, inspired by the last year spent caring for my two-year old granddaughter. I did the story and artwork. My next project (funded by the Canada Council, whoopee!) is to write the first in a series of biographies for children ages 8 - 12. It will be based on oral history interviews with all kinds of Canadian women who have done fascinating things.

Tuesday, February 22, 2022

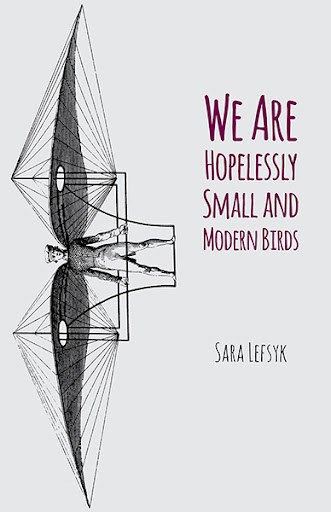

Sara Lefsyk, We Are Hopelessly Small and Modern Birds

I TOLD THIS SMALL MAN: if I had a mule, a parachute and long, flowing locks, I would jump out of this plane, put you in my shopping cart and push you to Brazil where we would change our names, cut our hair, and join the local militia. After that, we would lead a small army of chickens to the sea and, after many days of floating, I would catch a small fish and name it Pavlov. Then we would all jump into the sea and swim until we reached the largest island in Europe, where we would start a mariachi band with my birth family and yours and the sun would set and we would all drink sugar water and go to sleep beneath a large curtain of black air.

Thanks to the author, I recently acquired a copy of Ethel Zine maven Sara Lefsyk’s full-length debut, We Are Hopelessly Small and Modern Birds (New York NY: Black Lawrence Press, 2018), a book-length suite of prose poems writing (according to Jeff Friedman’s back cover blurb) “a small ward in a hospital the size of a universe, Heidigger, Kant, a small man who speaks in parables, numerous messiahs, hundreds of birds and animals, a strange doctor and his son, birds that need watering, and ‘pharmacological pancakes.’” Going through my files, it is curious to realize that a selection of the poems included here appeared previously in her chapbook A SMALL MAN LOOKED AT ME (Little Red Leaves, 2014), a title I reviewed (and very much enjoyed) soon after it appeared.

The prose poems in We Are Hopelessly Small and Modern Birds are curiously built, with each stanza-block existing as a single breath, a single thought, composing a semi-ongoing narrative amid lyric bursts. Through a lyric of surreal narratives, Lefsyk’s poem offer a story that exists in a shimmering dream-state, shifting in and out of focus. “OCCASIONALLY,” she writes, to open a poem early on in the collection, “OUR APARTMENT COMPLEX floats out to sea. As it was, Kant and I had our noses somewhere in the distance. ‘Most likely there is no meaning in things,’ Kant says. ‘Or only in the ultimate logic of certain animal forms and avian noises.’ // For this reason my bones feel like the small broken bones of a very tiny goldfish.” Set in five sections with an opening salvo, a poem-as-dedication “for and after FEDERICO GARCİA LORCA,” her narrator speaks from a ward and of doctors, dentists, husbands and philosophers in poems composed out of a kind of easy-flowing, clear and liquid motion. As well, there is something interesting about the way she writes of the body and the self, the narrator writing from a perspective that verges on primal, seen through a surreal lens. “IF I WERE A WIFE and a mother I would be a wife and a mother.” she writes, mid-way through the collection. “All my children say: ‘Build me,’ but the son takes my pelvis and runs it through the supermarket. // I go into and out of this supermarket whenever I want.” After having gone through this collection, I’m genuinely curious to find out what she’s been working on since.

IF THEY WERE COUNTING us all they were counting us all like they did yesterday only this time they would miss me in the numbers today.

Then they would force us onto our feet and we would pray for there not to be ropes and if there were ropes we would pray.

Arrange yourself.

The dr. himself would kneel before us and stick things places i can’t even talk about

and we won’t even cry a little about it.

They found my t-shirt but not me in it in the prayer room. They found my silence and my t-shirt and i did pray.

Bless me, they found my whole body in some dentist’s apartment and rotated it until they found its brilliance.

My upper jaw cit into my pelvis and i became some good factory.