My lines insist upon what

is:

you stalk me in the hill’s

green gestures,

saying, Deare hart,

how like you this?

Expect another, longer letter soon. (“FIRE

FLOWER”)

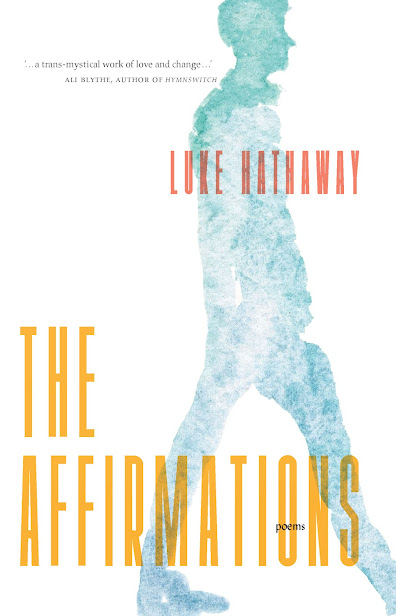

The fourth full-length poetry title, following Groundwork (Windsor ON: Biblioasis, 2011), All the Daylight Hours: poems (Toronto ON: Cormorant Books, 2014) and Years, Months, and Days: poems (Biblioasis, 2018), and the first I’ve read by Halifax poet and composer/librettist Luke Hathaway is The Affirmations (Biblioasis, 2022), a book that examines, as much as anything else, poetic form. For example, the second piece in the collection is the extended “NEW YEAR LETTER,” a ten-part epistolary experiment across a dozen pages that opens with a lyric explanation, citing W.H. Auden’s own work in the form, the book-length poem New Year Letter (1941). As Hathaway explains:

In January 2018, I decided to try my hand at my own verse letter to a friend, a devotee of Auden, with whom I had been in conversation in person and in letter around some of Auden’s themes. Auden appears in my letter; so does the poem Richard Outram, who had died of hypothermia—his choice—a dozen Januaries earlier, and whose work I was studying at the time I wrote these lines. There are other spirits, familiar and unfamiliar—the poet Rilke, they lay-theologian Charles Williams, one of Bach’s unknown librettists, the great poet Anon…—but for the most part they are like guests at a dinner party: one doesn’t need to know their names (I hope) in order to enjoy the conversation.

As the seventh part of Hathaway’s sequence offers:

This morning I can hear

the wind:

it held its fire on the

morning

I was walking on the

river,

talking to you in my

mind,

but right now it howls

around

my study. I can hear it

in

this poem, the loneliness

of letters:

this although the poets

say

before the word was sign

or symbol,

sacrament, or flesh and

blood,

it was this—what? This gap,

this Love.

Wiman calls Christ ‘contingency’.

What happens, to the God’s

what is.

Sometimes I pray to that

what is—

to help me value, as you

say,

the actual over the

possible,

and over freedom, yes,

the good:

O da quod jubes, Domine.

Meanwhile what happens

picks its way

amid the matted river sedges,

in among the hawthorn

branches,

out on the wide river

ice,

accident and happenstance

and chance encounter and

the glancing

blow. Christ! Can

one pray to that?

Hathaway sketches precision narratives across rhythms as skin across a drum, tightening the lyric when required, for higher effect. “The lights when on / and instantly // I saw it: you,” he writes, to open “EROS AND PSYCHE,” immortal; I, // consigned to any / trial your mother // might devise / (beans, rice, // golden fleece / in the thorn tree, // pick-up Styx): [.]” His is a storytelling lyric, perhaps echoing the story-and-song-telling of the libretto, composing examinations and observations and narratives that lean into the ethereal of lyric patters, lullaby, epistolary, essays and operatic nocturnes, and a wordplay of grand theatrical gestures. Hathaway seems to explore the boundaries of poetic form as it relates to an operatic storytelling, pushing at the edges of older forms with a new hand, and a new eye, and seeing what just might be possible. As part of “A POOR PASSION,” subtitled “after Bach’s Johannes-Passion,” Hathaway writes:

I am not the first poet-translator, in English or otherwise, to offer up new words for Bach’s Johannes-Passion. There is a long tradition of this kind of work, which musicologists sometimes call contrafactum—a kind of poesis ‘whereby the music is retained and the words altered’ (OED). Common in medieval and Renaissance music, the practice is still with us in folk song and in hymnody—and of course in childhood: ask any six-year-old who has gleefully chanted, Joy to the world, the school burned down….The practice of contrafactum has analogies in written verse (think of stanzaic poetry) and in life. (What am I, post-transition, but an old tune with new lyrics?)

No comments:

Post a Comment