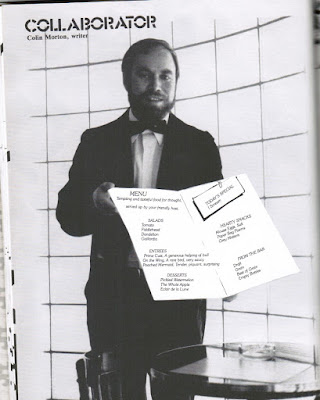

Ottawa writer and editor Colin Morton is the

author of numerous poetry books and chapbooks, including In Transit (Thistledown Press, 1981), This Won’t Last Forever (Longspoon Press, 1985), The Merzbook: Kurt Schwitters Poems (Quarry

Press, 1987), How to Be Born Again (Quarry

Press, 1991), Coastlines of the

Archipelago (BuschekBooks, 2000), Dance,

Misery (Seraphim Editions, 2003), The

Cabbage of Paradise (Seraphim Editions, 2007), The Local Cluster (Pecan Grove Press, 2008), The Hundred Cuts (BuschekBooks, 2009), and Winds and Strings (BuschekBooks, 2013)—as well as the novel Oceans Apart (Quarry Press, 1995).

Morton grew up in Alberta, and moved to Ottawa

soon after completing an MA in English at the University of Alberta in 1979. He

has performed and recorded his poetry with First Draft and other music poetry

groups, and his collaboration with Ed Ackerman, the animated film Primiti Too Taa (1988), based on Kurt

Schwitters’ Ursonate (Sonata in primitive

sounds), led to a Genie nomination, a Bronze Apple, and other international

film awards. He has been writer-in-residence at Concordia College (Moorhead,

MN, 1995-6) and Connecticut College (New London, CT, 1997).

From 1982 to 1989, he was editor and publisher

of Ouroboros, an Ottawa-based publishing house that produced books, chapbooks

and ephemera, producing works by himself, as well as a number of poets around

him at the time, including Susan McMaster, Chris Wind, Robert Eady, Margaret Dyment and John Bell, and culminated in the anthology Capital Poets, which included work by Nadine McInnis, John Barton,

Christopher Levenson and John Newlove. He is currently one of the organizers of The TREE Reading Series.

Q: What was the original impulse for starting

the press?

A: In the summer of 1982, the Tree Reading

Series organized Word Fest, a 2-day poetry festival at SAW Gallery in ByWard

Market, Ottawa. I edited a chapbook of the featured readers’ poems and worked

with artist Carol English to produce the booklets. At the end of the two days

of readings I came home hyper-excited and wrote my “Poem Without Shame” in one

night-long beat-inspired cry. I thought a lot of the poem and wanted it out there.

The prospect of sending it away to magazine editors and waiting a year maybe

two before seeing my poem printed almost secretly in some little journal did

not appeal to me. I liked the fold-old broadsheets that the League of Canadian

Poets had produced for some of its members, and I thought that would be a way

to get my poem shamelessly out into public. I chose a rigid cover stock and

asked Carol English to adorn my poem with some cover art – something suitably

surrealist – and the broadsheet was ready to hand out at readings.

From the start, I liked the idea of being able

to control how the printed product looked. I naturally looked around for other

projects.

Q: Were you part of the Tree Reading Series at

that time? What other activity, whether readings or publishing, were around you

at that time in Ottawa?

A: I had some production experience out west

with NeWest ReView, Literary Storefront Newsletter and

others, so Tree recruited me to create the WordFest catalogues. Ouroboros

authors Susan McMaster and Margaret Dyment I met at Tree readings, and others,

like Marty Flomen’s Orion series and Juan O’Neill’s Sasquatch. Christopher

Levenson edited Arc magazine, then

only a few years old, and hosted Arc readings as well. Ouroboros published

several of the Arc poets – John Bell,

Robert Eady and, later in the Capital

Poets anthology (1989), Levenson, Nadine McInnis, Sandra Nicholls, John

Barton, Blaine Marchand ... all these poets later published in solo editions by

Quarry Press out of Kingston, Ontario. So it was a fairly busy time for poetry

in Ottawa.

In addition to all that, I had weekly meetings

over coffee and beer with First Draft, a collective of writers, musicians and

artists who closed out Theatre 2000 near Byward Market in 1983 with a

multimedia performance that including my recital of “Poem Without Shame,” “wordmusic”

collaborations and others. The following year, 1984, saw First Draft’s third

annual group show appear in the form of a book from Ouroboros – an artist’s

book designed by Claude Dupuis of Ottawa. Dupuis filled every corner of every

page with visual information, leaving the printer literally no margin for

error. The result is The Scream, by

far the most ambitious piece of book-making Ouroboros attempted. Smaller

projects did use the visual resources of Ottawa’s print shops, and my own

desktop publishing efforts. Visual poetry predominated in postcards, posters

and chapbooks.

Q: What do you feel your activity through Ouroboros

accomplished, and what prompted the press to finally fold?

A: About the time I was rounding up operations

at Ouroboros, I had a phone call from John Buschek, who was thinking of

starting up his own literary press and asked if I had any advice. I told him it

would be a good idea to keep it small. Keep it small so that every project you

undertake receives your full attention and love. (By this time I had decided to

give my full creative attention to writing novels, one of which was eventually

published by Quarry in 1995.) The second piece of advice I gave Buschek was to

produce exactly what he wanted. We go into the arts, after all, to create

something of ourselves, we don’t write books, or print and distribute them, to

fulfill someone else’s dream. I’m glad to see BuschekBooks continuing to grow,

a little at a time and, reflecting on the Ouroboros years, I’m glad I could

bring those writers to wider public exposure, and to draw attention to Ottawa

as a place to make art and literature, to talk and argue about art and

literature, because these things matter.

Q: I’m curious about the activity you were

involved with out west, before you moved to Ottawa. What prompted the move, and

what differences did you see between the communities?

A: This is reaching back into the 70s, into the

real arts-and-crafts era of little magazine production. I was involved in

little magazines from high school, on though university and after. In 1973, I

co-edited Harbinger, an anthology of

southern Alberta writing that included Erin Mouré, Andy Suknaski and others. Later, at the NeWest ReView office, we received long strips of copy that we had

to glue into straight columns by eye. Layout really was a matter of cut and

paste. It could get messy. At Vancouver’s Literary Storefront there would be

collating parties, a collective effort to get the monthly publication out on

the streets before the events they announced. That was social media in those

days.

Like a lot of people, I moved to Ottawa for the

work – my wife Mary Lee’s work first and eventually my place in the publication

division of a federal department. After supply teaching in Vancouver, I’d have

gone anywhere at the first hint of an opportunity. After Vancouver, which had

an established literary culture with factions and rivalries, Ottawa was more

like Calgary and Edmonton – smaller, just getting active, open to newcomers and

new ideas.

Q: The press ended on a high note, with the

publication of the anthology Capital

Poets. In many ways, the anthology represents just as much the aesthetic of

the press as the poets active around you at the time. What was the selection

process for the anthology?

A: Here’s one of the difficulties in

reconstructing literary history. Capital

Poets has a finished look to it, and you might see it as a landmark – the eighties

generation in Ottawa. But it isn’t that and it didn’t set out to be. My

original idea was to put out a monthly leaflet featuring a single writer each

month – poetry or fiction or whatever – an author spotlight that could be

distributed at readings or given away in bookstores or through the mail. A

continuing series.

Two moments’ thought about the economics of the

enterprise, though, reveals the problem. We are deluged by a flood of paper; we

throw it away, often unread, whether it’s this week’s ads or poetry for the

ages. No, the practical way to highlight Ottawa’s writers was through an

anthology, up to ten pages from each of ten writers, printed and bound to be

kept and remembered a generation later.

Capital Poets

represents the poets I spent time with in the eighties, many of whom had connections

to Arc and Tree and other literary

groups. In a way, the collection was just as important for the writers who

weren’t included in the anthology. It mobilized some to create their own

anthologies, like Seymour Mayne’s Six

Ottawa Poets and Luciano Diaz’s broader Symbiosis

collections. In retrospect, I guess Capital

Poets is a kind of landmark; it’s from then that Ottawa writers really

start looking at ourselves as a community of interests. When I see Ottawa’s

varied literary communities cooperating in our annual VerseFest, WritersFest and

so on, I appreciate how much the city has matured, culturally, and how much it

continues to change.

Q: Well, and I know, too, of a whole slew of

Ottawa poets who didn’t respond to your anthology by putting out one of their

own, such as the loosely-grouped poets around Gallery 101: Dennis Tourbin,

Michael Dennis, Riley Tench, Ward Maxwell, etcetera. What was the response to

the anthology when it appeared?

A: Not to mention Diana Brebner and Marianne

Bluger, both emerging nationally about that time. The response to the anthology

was vigorous, back pre-Internet when the letters to the editor page gave one a

loud blowhorn. Again, the outsiders came across as more scandalized than the

insiders were pleased. They took their own inclusion for granted, I guess. I

could have gone ahead and published a second volume in the series. There were

obviously the poets to fill one out, but the anthology field seemed well

ploughed by that time, and I imagined writing would be a more satisfying use of

my time, which it was.

Q: Was it as simple as that, then, choosing

your writing over the publishing? You add Brebner and Bluger to my shortlist;

who or what else emerged during the period you were producing Ouroboros?

A: A number of things were wrapping up around

that time.

After theatrical productions of Susan McMaster’s

Dark Galaxies and my Kurt Schwitters

piece, The Cabbage of Paradise (with

3 actors and a 12-voice sound poetry choir), First Draft disbanded and members

Andrew McClure and David Parsons moved to Toronto.

My writing was going more and more into prose

and narrative, so the cross-media emphasis of Ouroboros was less top-of-mind.

The response to Capital Poets was disappointingly parochial (the opposite of what

I’d hoped the anthology would show).

At the day job, the big public service strike

started me thinking of going freelance instead. My son was going off to

university, and soon I would be offered writer-in-residence gigs in the U.S.

Things end for lots of reasons; more mysterious

is why some continue on despite the changes.

Memories tend to be short, and some exciting

developments can be forgotten until someone like you, rob, comes along to

preserve the memory somehow.

Ottawa in the 80s saw the emergence of valuable

venues like Gallery 101, where Dennis Tourbin animated literary events. There,

and at SAW Gallery, performance artists like Paul Couillard and Louis Cabri

were exploring language in the visual arts context.

The National Library was a regular venue for

national, international and local writers, thanks to Randall Ware’s direction.

Ottawa was a centre for the Chilean diaspora writers

like Jorge Etcheverry and others though Split Quotation Press.

Patrick White’s Anthos magazine ran as a quarterly tabloid. There were regular

reading series like Tree, Orion and Sasquatch.

Young writers were maturing and first books

were coming out. Blaine Marchand, though Ottawa Independent Writers (another

new organization then), introduced the Archibald Lampman Award.

Bywords

emerged from Ottawa U. as a monthly newsletter preceded, I believe, by another

monthly newsletter edited by James Cassidy.

Then as now, poets migrated to Ottawa from

across the country – John Barton and Stephen Brockwell, for instance – and international

poets were attached to embassies – like Shaheen who wrote ghazals in Urdu.

The trouble with such lists, like anthologies,

is that something will be left out. But maybe this is enough to suggest that

the Ottawa literary scene wasn’t a blank slate before the present generation

arrived.

Q: In hindsight, what do you consider the

biggest accomplishment of the press?

A: I'm inclined to let others decide what

Ouroboros achieved. It might be the publication of the first book by Susan

McMaster, Dark Galaxies; or the last

long-poem by John Newlove, “In Progress” in Capital

Poets; or a performing book like no other, The Scream.

But there’s something else, more personal.

I’m reminded of the Kafka parable about the man

who waits his whole life at the door of the castle to be admitted. No one ever

comes to invite him inside, and when it’s too late he realizes all he needed to

do was to walk through that door. By publishing Ouroboros, I learned that

Literature is not some great edifice or institution that we writers have to

approach with our begging bowls. It is the sum of everything writers,

publishers, critics do. As you know, rob, we just have to be bold enough to

walk on past the gate-keepers.

Ouroboros Bibliography

Broadsides

1982 – Colin Morton, “Poem Without Shame” (8.5 x 14,

3-fold); art by Carol English

1983 – Susan McMaster, “Seven Poems” (8.5 x 14, 3-fold);

art by Claude Dupuis

1983 – John Bell, “The Third Side” (11 x 17, 4-fold); art

by Suanne Rogers

1986 – Chris Wind, “The House that Jack Built” (11 x 17

poster)

1989 – Richard Kostelanetz, “Openings” (8.5 x 11, 3-fold)

Chapbooks

1983 – Margaret (Slavin) Dyment, “I Didn’t Get Used To It”

(24 pp.); art by Claude Dupuis

1987 – Colin Morton, “Two Decades: from A Century of Inventions” (28 pp.)

1989 – Nancy Corson Carter, “Patchword Quilt” (16 pp.)

Books

1984 – The Scream:

First Draft; the third annual group show (96 pp.); writing by Colin Morton,

Susan McMaster, Nan Cormier; music by Andrew McClure, Andrew Parsons; art by

Claude Dupuis, Carol English; design by Claude Dupuis

1985 – Robert Eady, The

Blame Business (50 pp.); cover art by Darien Watson

1986 – Susan McMaster, Dark

Galaxies (50 pp.); cover art by Roberta Huebener

1989 – Capital Poets (96

pp.); poetry by John Barton, Margaret Dyment, Holly Kritsch, Christopher

Levenson, Blaine Marchand, Nadine McInnis, Susan McMaster, Colin Morton, John

Newlove, Sandra Nicholls

Postcards

1983 – Colin Morton, “Dialogue 1” “Dialogue 2” “Dialogue 3”

“Dialogue 4”

1984 – Penn Kemp, “Incremental”

1984 – Colin Morton, “Twins”

1984 – LeRoy Gorman, “moon”

1985 – Noah Zacharin, “Blues”

1985 – Colin Morton, “I read a shadow on the stream”

1985 – Robert Eady, “Amnesty” “The Lie” “Concise History of

a Room” “How to Lube a Car”

1987 – Maureen Korp, “Melting Ice” (with art by Mitsu

Ikemura)

No comments:

Post a Comment