Thursday, April 30, 2015

Wednesday, April 29, 2015

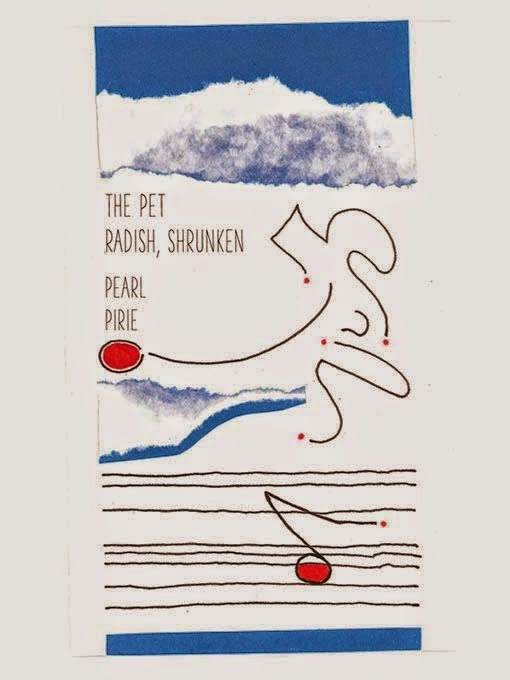

Pearl Pirie, the pet radish, shrunken

My short review of Pearl Pirie's the pet radish, shrunken (BookThug, 2015) is now online at The Small Press Book Review.

Labels:

BookThug,

Pearl Pirie,

The Small Press Book Review

Tuesday, April 28, 2015

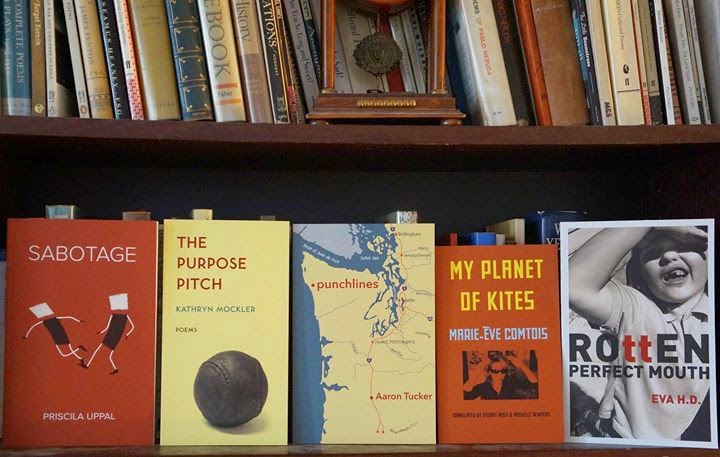

Eva H.D., Rotten Perfect Mouth

Still

Life With Canadiana

The wind is going a

hundred

miles an hour, mewling

in the chimney like a

vodkathin drunk.

Pale broadloom, an

automated

snowman. Three girls

grow in choir

robes on the mantel:

from left to right

their hair and faces

lengthen.

The microwave is

humming,

and the lights on the

tree.

Pitch-perfect, two

sisters on

matching florals grow

limber

with Kahlua. Above the

wind,

and below it, they

scale the melody’s

frame, and descend.

Another sister pads in,

towelling

dry her long, blonde

hair, braiding

in a harmony.

In the hall, their

mother and aunt

pause a discussion on

cats.

On the sofa, their

great-aunt closes

her eyes.

When the song is done,

their father says

Dinner, and the middle sister disappears

for a cigarette.

The frozen yard outside

is so quiet,

she thinks it must have

snowed

all over the world.

There

is something quite remarkable in the poetry of Toronto poet Eva Haralambidis-Doherty,

otherwise known as Eva H.D., through her first poetry collection Rotten Perfect Mouth (Toronto ON:

Mansfield Press, 2015). Remarkable, and rare, in the fact that she hadn’t published

a single word before the appearance of this collection (something she shares

with Ottawa poet Jennifer Baker, who didn’t publish a word before the appearance of her recent first chapbook, as well as Calgary poet Nikki Sheppy).

In her opening salvo, Rotten Perfect

Mouth is a strong and compelling collection, and one from a poet I very

much hope we hear more from. Her powerful and playful poems exist as a series

of lyric narratives constructed out of personal observations, writing out

stories of meteors and lies, various locations in and beyond Toronto, oceans,

daydreams and conflicts, among other subjects both abstract and immediately

concrete. There is a curious surrealism that permeates Eva H.D.’s

collection, one that includes occasional, incredible quirks and connections that

leap off the page. During her recent reading as part of the Ottawa Mansfield

Press launch I could hear elements of the late American writer Richard Brautigan’s poetry, and his ability to blend opposing thoughts into unexpected

images. There is something lovely and lyric and unusual in her poetry worth

paying attention to, a kind of staccato pulse that races through her lines as

she writes “The snow is pounding down / like a herd of ballerinas, / and fills

up the window / between MYSTERY and / ROMANCE / with its white weight.” (“Why

Basements Are Safe”), “The sky never touches the ground but races it, forever

and ever. / Amen.” (“Racing It”), or the opening of the poem “Liberty Bell,”

that reads:

Your fern hands, those

saturated fronts

pealing down my ribcage,

you Liberty Bell.

Furling and unfurling,

green as tides,

and they are cream,

snapping like sails,

tapered tethered doves.

The wingbeats a

delicate violence.

Each one a fluttering,

fickle heart,

daubing the air.

My little hypotenuse.

My champagne

cork. My crocus. My

snowdrop. My

holy holy shit.

My friendless renard,

all tipsy

with va et vient. You

jibtop.

Labels:

Eva H.D.,

Mansfield Press,

Richard Brautigan,

Stuart Ross

Monday, April 27, 2015

rob mclennan interview : Writer's Block CJSW

Emily Ursuliak was kind enough to interview me over at University of Calgary's CJSW radio program Writer's Block. You can now listen to the interview here.

Labels:

audio,

CJSW,

Emily Ursuliak,

interview,

rob mclennan interview,

Writer's Block

Sunday, April 26, 2015

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Andrew Forbes

Andrew Forbes was born in Ottawa, Ontario, and attended Carleton University. He has written film and music criticism, liner notes, sports columns, and short fiction. His work has been nominated for the Journey Prize, and has appeared in The Feathertale Review, Found Press, PRISM International, The New Quarterly, Scrivener Creative Review, The Journey Prize Stories 25, This Magazine, Hobart, The Puritan, All Lit Up, The Classical, and Vice Sports. What You Need, his debut collection of fiction, is available from Invisible Publishing. He lives in Peterborough, Ontario.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Well, as this is my first book, I suppose whatever changes it’s to bring are currently underway, and I won’t be able to view them fully except in hindsight. Can I take a raincheck on this question?

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

I think I came to fiction because it was the form that gave the most to me as a reader. I write non-fiction too, though not, as yet, in book form. Poetry is another language, the faculty for which I seem to lack entirely.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I always have something on the go, usually many things. Stories, essays, baseball writing. If something isn’t working I move onto something else. Some stories happen all at once, while some take two or five or seven years of effort, then abandonment, then effort, etc. When things are really working, I’m a pretty fast writer, I think. As for the differences between first and final drafts, I’d say that I’m a prodigious tinkerer, always fiddling with the smallest things until finally walking away. My starts are quick, generally. I make a few notes and sit on an idea for a period of time, and then leap in. Essays are like that, too. Once I’m rolling the thing seems to unfurl itself out in front of me. That’s a nice feeling.

4 - Where does a work of fiction usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

For me a work of fiction often begins with an image, or a setting. Occasionally it’s a line, which generally ends up being the first line, though it has also become the last, in a few instances. I am a big believer in using past failures as stock material, stripping them for parts -- scenes, settings, dialogue -- for newer, hopefully more successful things I’m working on. It’s a way to convince myself I wasn’t wasting my time.

In the case of this, a book of short stories, each piece is built on its own, though I’d say that for several years I had been aware that I was putting together a collection. That meant that certain stories were left out, not because they weren’t “good enough,” but because they simply didn’t fit.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Public readings are a peculiar thing, seemingly at complete odds with the impulse which drove me to writing in the first place, as a very young person: I’d always seen writing as a way for me -- a pretty shy kid, prone to mild social anxiety -- to say things I couldn’t say aloud. Flash forward a decade or two and see me being asked to stand in front of a roomful of people and read those things. Seems like a bit of a cruel joke, doesn’t it? But I’m getting better at them, I think. A bit more comfortable.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

If form is theory, then I’m certainly concerned with that, insofar as I’m interested in using the constraints of the short story form to my advantage. As for questions, they remain specific to each piece, for now, though I suppose that if you were to view them all in macro you’d see the same questions repeating: what does this person want? what are the forces which prevent them from getting it? etc. The broad human questions. What am I doing? What’s the point? That sort of thing.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

On the one hand, I think there’s some danger to anointing ourselves spokespeople for a culture, assuming that our concerns are in any way universal. Writing is a privileged act, when you get down to it. But on the other hand, yes, I think we can strive to be sentinels, loudspeakers, canaries in the coalmine, squeaky wheels. Writers can and should say difficult things in the hopes that those things become easier for everyone to say.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I think I’ve been lucky with editors, overall. I’ve been edited by a few people at the magazine or journal level who were obviously interested in bringing out the best in a piece. I have been largely spared the horror of a personality clash with an editor. And while I had extreme trepidation over handing over my book to an editor, the experience turned out to be uniformly rewarding. I had a great working relationship with Michelle Sterling, and there’s no question that she made the book better than it was when it was given to her.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

“Read, write, push.” That’s the mantra of Rick Taylor, writer and teacher, and friend, and it pretty much sums up the whole thing for me.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (fiction to non-fiction)? What do you see as the appeal?

I’ve done a fair bit of non-fiction work now, mostly writing about sports, and music, and movies, and I enjoy those things. Fiction steps in when the precise truth of a thing is in some way narratively inconvenient to me, but for a lot of stories--the way Ichiro Suzuki goes about his business, say, or the circumstances of Albert Ayler’s life--the truth is simply so much better than what I could come up with, so I deal with the material in a non-fictional manner. The subjects have a way of telling you whether they’re best suited for one treatment or the other.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I’m up early, which is something I’ve done for a long time. The first house my wife and I owned, in rural eastern Ontario, had a sunroom on it which faced east. The whole thing was windows, basically. It was lovely and quiet. I had a chair out there, and I’d be up in time to get started before the sun came up, a pot of coffee close at hand. I could get a fair bit of work done before going to work-work, which at that time might have been in a music store, or it might have been an internet company which rented DVDs to subscribers by mail, depending on just when this historical vignette takes place. That schedule proved very productive for me. I produced, even if I produced little of value. I pumped out drafts, the necessary bad, early ones, which are prerequisite to better stuff. So getting up early has remained my preferred method. If I can get a couple of hours in before the first kid stirs, I’m happy.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I look to writers who are way, way better than me. I’ll go to the shelf and pull down a collection by Lorrie Moore or Alice Munro or Jim Shepard.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

A flowering lilac bush. That’s two-staged. My grandmother’s house in Pictou, Nova Scotia had a big old lilac tree outside, and the scent, alongside the damp earthen smell of the cellar, defined that place for me. Then that house in Eastern Ontario had a lilac bush on the property, and the smell of it in May or early June, when summer was just coming into its lush fullness, was about the most comforting thing in the world to me. Coming through an open window at night. Then I’d clip big bunches of it and put them in water on the table, but in a matter of hours they’d begin smelling rank. The scent of it on the breeze couldn’t be duplicated. There’s probably some deeper lesson in that.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

All of it, I suppose. Music, certainly. Whether through lyrics or melody or both, music has always fueled something. I often wish I possessed some musical ability, because it just seems like a much more direct route to whatever emotional truth I’m trying to tap with words. I use it when writing, usually instrumental, often John Coltrane. I’ve also had stories spring from songs -- Neko Case inspired one of the stories in the book, for example. Movies contribute too, as does photography. News items. Everything, really. As a writer you’re kind of a sieve of information, aren’t you? Nature is the calming force, the healer. If I can steal the opportunity to swim in a lake I’m recharged for whatever labours lie ahead.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Five years ago, when my twin boys were born prematurely, and they were housed in the hospital’s strange clear boxes, with ultraviolet lights trained on them and tubes running into them, computers hooked up to them, I would go in there at night, sit in a rocking chair, and read them Whitman.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Attend the World Series.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I’d like to do something with clearer, more tangible results. A contractor, maybe. Something where, at the end of the day, I could point to the wall I’d put up and say, “That. That’s what I did today.” Paragraphs, word counts, they seem a little inconsequential as compared to a wall.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I’ve shown very little aptitude for anything else. Once, deeply concerned for my prospects, my father sent me to a career coach guy, and footed the bill. This man was straight out of central casting -- cigarette-chomping, slicked-back greying hair, Italian suits. He had no idea what to do with me. At one of our meetings, he simply had nothing to say. He put his hands behind his head and his feet up on his desk, exhaled heavily, and then, nodding toward his feet, said, “Business tip: your socks should match your pants.” He subjected me to a battery of personality tests, and when the results came back he slid a folder across his desk to me and said, “It says you should be a writer.”

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I just reread Birds of America by Lorrie Moore. Genius. And it was a few months back, but one night TCM was showing Smiles of a Summer Night. I turned it on and my daughter, who’s eight, came and sat with me, and she was engrossed. On the one hand it was a bit beyond her, I guess, this subtitled Bergmann film about sexual mores in turn-of-the-century Sweden, but though outside her frame of reference she seemed to relate to it, maybe most strongly to Anne, the sort of caged-bird character, that uncertainty over what the world’s offering you at a pivotal point in your life. She also really liked the costumes. Anyway, that movie, and the experience of watching it with my kid, was memorable.

20 - What are you currently working on?

Dinner. A bacon and broccoli rice bowl. Should be ready in about twenty minutes.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Well, as this is my first book, I suppose whatever changes it’s to bring are currently underway, and I won’t be able to view them fully except in hindsight. Can I take a raincheck on this question?

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

I think I came to fiction because it was the form that gave the most to me as a reader. I write non-fiction too, though not, as yet, in book form. Poetry is another language, the faculty for which I seem to lack entirely.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I always have something on the go, usually many things. Stories, essays, baseball writing. If something isn’t working I move onto something else. Some stories happen all at once, while some take two or five or seven years of effort, then abandonment, then effort, etc. When things are really working, I’m a pretty fast writer, I think. As for the differences between first and final drafts, I’d say that I’m a prodigious tinkerer, always fiddling with the smallest things until finally walking away. My starts are quick, generally. I make a few notes and sit on an idea for a period of time, and then leap in. Essays are like that, too. Once I’m rolling the thing seems to unfurl itself out in front of me. That’s a nice feeling.

4 - Where does a work of fiction usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

For me a work of fiction often begins with an image, or a setting. Occasionally it’s a line, which generally ends up being the first line, though it has also become the last, in a few instances. I am a big believer in using past failures as stock material, stripping them for parts -- scenes, settings, dialogue -- for newer, hopefully more successful things I’m working on. It’s a way to convince myself I wasn’t wasting my time.

In the case of this, a book of short stories, each piece is built on its own, though I’d say that for several years I had been aware that I was putting together a collection. That meant that certain stories were left out, not because they weren’t “good enough,” but because they simply didn’t fit.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Public readings are a peculiar thing, seemingly at complete odds with the impulse which drove me to writing in the first place, as a very young person: I’d always seen writing as a way for me -- a pretty shy kid, prone to mild social anxiety -- to say things I couldn’t say aloud. Flash forward a decade or two and see me being asked to stand in front of a roomful of people and read those things. Seems like a bit of a cruel joke, doesn’t it? But I’m getting better at them, I think. A bit more comfortable.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

If form is theory, then I’m certainly concerned with that, insofar as I’m interested in using the constraints of the short story form to my advantage. As for questions, they remain specific to each piece, for now, though I suppose that if you were to view them all in macro you’d see the same questions repeating: what does this person want? what are the forces which prevent them from getting it? etc. The broad human questions. What am I doing? What’s the point? That sort of thing.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

On the one hand, I think there’s some danger to anointing ourselves spokespeople for a culture, assuming that our concerns are in any way universal. Writing is a privileged act, when you get down to it. But on the other hand, yes, I think we can strive to be sentinels, loudspeakers, canaries in the coalmine, squeaky wheels. Writers can and should say difficult things in the hopes that those things become easier for everyone to say.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I think I’ve been lucky with editors, overall. I’ve been edited by a few people at the magazine or journal level who were obviously interested in bringing out the best in a piece. I have been largely spared the horror of a personality clash with an editor. And while I had extreme trepidation over handing over my book to an editor, the experience turned out to be uniformly rewarding. I had a great working relationship with Michelle Sterling, and there’s no question that she made the book better than it was when it was given to her.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

“Read, write, push.” That’s the mantra of Rick Taylor, writer and teacher, and friend, and it pretty much sums up the whole thing for me.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (fiction to non-fiction)? What do you see as the appeal?

I’ve done a fair bit of non-fiction work now, mostly writing about sports, and music, and movies, and I enjoy those things. Fiction steps in when the precise truth of a thing is in some way narratively inconvenient to me, but for a lot of stories--the way Ichiro Suzuki goes about his business, say, or the circumstances of Albert Ayler’s life--the truth is simply so much better than what I could come up with, so I deal with the material in a non-fictional manner. The subjects have a way of telling you whether they’re best suited for one treatment or the other.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I’m up early, which is something I’ve done for a long time. The first house my wife and I owned, in rural eastern Ontario, had a sunroom on it which faced east. The whole thing was windows, basically. It was lovely and quiet. I had a chair out there, and I’d be up in time to get started before the sun came up, a pot of coffee close at hand. I could get a fair bit of work done before going to work-work, which at that time might have been in a music store, or it might have been an internet company which rented DVDs to subscribers by mail, depending on just when this historical vignette takes place. That schedule proved very productive for me. I produced, even if I produced little of value. I pumped out drafts, the necessary bad, early ones, which are prerequisite to better stuff. So getting up early has remained my preferred method. If I can get a couple of hours in before the first kid stirs, I’m happy.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I look to writers who are way, way better than me. I’ll go to the shelf and pull down a collection by Lorrie Moore or Alice Munro or Jim Shepard.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

A flowering lilac bush. That’s two-staged. My grandmother’s house in Pictou, Nova Scotia had a big old lilac tree outside, and the scent, alongside the damp earthen smell of the cellar, defined that place for me. Then that house in Eastern Ontario had a lilac bush on the property, and the smell of it in May or early June, when summer was just coming into its lush fullness, was about the most comforting thing in the world to me. Coming through an open window at night. Then I’d clip big bunches of it and put them in water on the table, but in a matter of hours they’d begin smelling rank. The scent of it on the breeze couldn’t be duplicated. There’s probably some deeper lesson in that.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

All of it, I suppose. Music, certainly. Whether through lyrics or melody or both, music has always fueled something. I often wish I possessed some musical ability, because it just seems like a much more direct route to whatever emotional truth I’m trying to tap with words. I use it when writing, usually instrumental, often John Coltrane. I’ve also had stories spring from songs -- Neko Case inspired one of the stories in the book, for example. Movies contribute too, as does photography. News items. Everything, really. As a writer you’re kind of a sieve of information, aren’t you? Nature is the calming force, the healer. If I can steal the opportunity to swim in a lake I’m recharged for whatever labours lie ahead.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Five years ago, when my twin boys were born prematurely, and they were housed in the hospital’s strange clear boxes, with ultraviolet lights trained on them and tubes running into them, computers hooked up to them, I would go in there at night, sit in a rocking chair, and read them Whitman.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Attend the World Series.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I’d like to do something with clearer, more tangible results. A contractor, maybe. Something where, at the end of the day, I could point to the wall I’d put up and say, “That. That’s what I did today.” Paragraphs, word counts, they seem a little inconsequential as compared to a wall.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I’ve shown very little aptitude for anything else. Once, deeply concerned for my prospects, my father sent me to a career coach guy, and footed the bill. This man was straight out of central casting -- cigarette-chomping, slicked-back greying hair, Italian suits. He had no idea what to do with me. At one of our meetings, he simply had nothing to say. He put his hands behind his head and his feet up on his desk, exhaled heavily, and then, nodding toward his feet, said, “Business tip: your socks should match your pants.” He subjected me to a battery of personality tests, and when the results came back he slid a folder across his desk to me and said, “It says you should be a writer.”

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I just reread Birds of America by Lorrie Moore. Genius. And it was a few months back, but one night TCM was showing Smiles of a Summer Night. I turned it on and my daughter, who’s eight, came and sat with me, and she was engrossed. On the one hand it was a bit beyond her, I guess, this subtitled Bergmann film about sexual mores in turn-of-the-century Sweden, but though outside her frame of reference she seemed to relate to it, maybe most strongly to Anne, the sort of caged-bird character, that uncertainty over what the world’s offering you at a pivotal point in your life. She also really liked the costumes. Anyway, that movie, and the experience of watching it with my kid, was memorable.

20 - What are you currently working on?

Dinner. A bacon and broccoli rice bowl. Should be ready in about twenty minutes.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Saturday, April 25, 2015

Pattie McCarthy, x y z & &

My little review of Pattie McCarthy's x y z & & (Ahsahta, 2015) is now online at The Small Press Book Review.

Friday, April 24, 2015

Damian Rogers, Dear Leader

As

If I Were Anything Before

Not all rocks

are alive. Or

so I’ve read.

Someone I love

is struggling, her thoughts

a coral net.

The pills fail.

Her chakras shatter.

I want to show her

the Canadian Shield.

I’m in Sudbury.

It’s snowing.

The pine trees looked

lovely as I drove

the treacherous roads.

I’m ill-equipped

for this. I sit

by a fake fireplace

that frames a real

flame.

I’ve been crossed

by two crows today.

The

long-awaited second poetry collection by Toronto poet and editor Damian Rogers

is Dear Leader (Toronto ON: Coach

House Books, 2015), a collection of poems rife with energy and beauty,

observation and tension, writing as deeply contemporary as might be possible in

poetry. Dear Leader, which appears

six years after her Paper Radio

(Toronto ON: ECW Press, 2009), is an exploration of hope, rage, memory, loss

and salvage struggling through a series of optimisms, in poems that attempt to

capture the minutae of everyday living, whether writing on and around explaining

ecology to a toddler, classic albums, villanelles and Mrs. Frank Lloyd Wright, or

notes sketching out a series of thoughts and ideas both casual and deep. There is

such a curious way that Rogers composes a poem around a thought, stretching and

searching across a great distance over a few short lines. “The Book of Going

Forth In Glitter” begins: “See the daughters of the screenshot / arrange their

arms like / the ladies in major paintings // for an online salon. See them

inventory / their makeup bags in popular verse. / What’s worse? My peeling skin

// or how my mind shrivels in its cap?” Or “The

Black Album On Acid,” that writes: “I’m at the centre of the never- /

ending night. // You pull me out.”

Certain

poems in the collection exist as short monologues or scene studies, such as the

poem “There’s No Such Thing As Blue Water,” that opens: “I’ve been thinking

that montage is a mental technique / for accepting unity as a convulsive

illusion. I feel sick. / I hate it when my stories have holes, though I suspect

/ there’s where the truth leaks out. So go back to bed.” Another piece, “Mrs.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Black Lambswool Coat,” opens: “And we were talking about

the house / parties where all the guests / try to describe / the milky void [.]”

I’m curious as to Rogers’ explorations in prose and the sentence, and wonder if

she might be leaning her way towards postcard fiction, easing slowly from one

genre into the possibility of another.

Dear

Leader

Fuck the

fourteen-year-old who flirted with my boyfriend. If I’ve turned ugly on the

inside, it’s all her fault. Where were you when my love split the planet in

two? I knew who would undo me. Did you grab her throat and drag her downstairs?

I’ve been betrayed by the boys who sprayed my name under the overpass, the ones

who walked me home in a pack, called me their tender pet. This isn’t over yet.

I eat you I eat you I eat

you.

There

is a complexity to her poems, and an anxiety that quickly emerges as well, as

from someone paying deep attention to the world, but not entirely pleased with what

is going on, and occasionally uncertain on the effects humanity has on itself

and the surrounding planet, as the end of the poem “Storm”: “We live in / the

arteries / of a large / ugly animal / and I saw / it move.” One of the finest

poems in the collection has to be her “Poem for Robin Blaser,” composed with such

a graceful ease and space of breath, and dedicated to the late, great Vancouver poet. “O,” she opens the piece, “I know your thoughts are with the gods, / so

young and loose.” The final couplet of the short piece, both lovely and

striking, manages to somehow exist as a distillation of the book as a whole:

You blew smoke at me and smiled.

Nothing is so easy.

Labels:

Coach House Books,

Damian Rogers,

Robin Blaser

Thursday, April 23, 2015

"Meteor" (new poem) : Cosmonauts Avenue,

I've a new poem, "Meteor," now online at Cosmonauts Avenue. Check out the new issue, which also includes new work by David McGimpsey (including an interview conducted by Mike Spry), Melissa Bull, Jennifer Sears, Andrew Purcell, Kevin Grauke, Coe Douglas and plenty of others.

Wednesday, April 22, 2015

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Raoul Fernandes

Raoul Fernandes lives and writes in Vancouver, BC. He completed the Writer’s Studio at SFU in 2009 and was a finalist for the 2010 Bronwen Wallace Award for emerging writers and a runner up in subTerrain’s Lush Triumphant Awards in 2013. He has been published in numerous literary journals and is an editor for the online poetry magazine The Maynard. His first collection of poems, Transmitter and Receiver is out this Spring from Nightwood Editions.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book is barely a month old at this date, so I'm in the dazed and delighted stage. But comparing my writing to my old chapbooks or online livejournal writing, I think I've become less overtly sentimental, and yet probably a bit more open to real feeling. Less cloaking. More attentive to syntax and the rhythms of the line. I think I've also allowed myself a range of new subjects I probably wouldn't have touched back then, flowers, computers, other people.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I started writing through that common angsty teenage pressure release valve. Lyrics in songs played a part too. I like how saturated in meaning some lines felt when strung together. And just being able to get in and out on a single page was appealing. I don't think I have the attention and capacity for fiction or non-fiction. Also when I was much younger, my elementary school teacher once complimented the first poem I wrote. That kind of thing goes a long way.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I've never seen my writing as a project. Most of my poems begins as messy unformed things, buried somewhere in sessions of automatic writing. If I see something that might survive, I keep working on it until it comes alive. And yes, this is after filling copious notebooks.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

My poems begin as tiny elements: an image, a phrase, a question. It grows from there. I told people I was working on a book for a while before it came out. But I was mostly only working on poems until near the end where I had to sequence. I think I still have to learn how to write books.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I really like them despite the nerves and rarely being as good as I want. It's very important for my work to connect with people. I write my poems towards that. It's such an intimate thing to have people sit quietly and listen to you, to have that trust. Especially with something as potentially volatile or bewildering as poetry. After, I want to kiss all their foreheads and say “sorry” and “thank you.”

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

Oh goodness. Well, I think I can speak only for myself. I find myself getting obsessed with certain human qualities: how we perceive things, how we try to make sense of this life. What is this sensation I have no words for? How do we get through the day? Why did that person set himself on fire? Do I want to set myself on fire on occasion? Things like that.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I imagine that a lot of poets who get to this question, pause and squirm a little. My first response is “I have no idea.” But if I pushed myself to get heady, this is what I might suggest: We all use language to make meaning out of life. And disrupting or charging that meaning-making machine, can make it spark and whir in really lovely ways. Maybe this ensures you're not taking it (or life) for granted. And we get to connect with each other on new playing fields. Even if it only happens in fleeting moments. I don't know if it is good for everyone, but it's been good for me. I think there are writers who write more overtly political and such--and that's terribly important--but I feel most of them still start with that simple function of lighting up your imagination.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Both. It really has to be a good fit or the dynamic can be very difficult. My editor was pretty hands off with my book, which was nice because I had already worked it through quite a bit with my first readers.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Doesn't it seem most good advice is what you already know, but for some reason haven't permitted yourself to follow? It's nice to hear it from another person. With writing it's probably the advice that suggests being very conscious of a reader. That and write much and often. Focus on quantity before quality.

10 -What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

If we're pretending it's my day off and somehow my 3 year old son has run off happily into the woods, you'll probably find me heading to a coffee-shop soon after breakfast and filling up a few pages my notebook. It's not very complicated. I try to (and have to often) write at different times of the day, but the morning is ideal.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

In the scenario above I have another book of poems beside me to dive into if I lose steam. In general, art, music and film helps too.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Probably an earthy post-rain garden and the smell of my wife and child. Though I don' t think I am reminded much of home unless I am home.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

All of the above, I'm sure. Music is probably the most emotional of those forms for me and probably has a direct connection to my writing more than the others.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

A handful in no particular order with apologies to the hundreds I am omitting: Bob Hicok, C.K. Williams, Dean Young, David Foster Wallace, Mary Ruefle, Matthew Zapruder, Lydia Davis, James Tate, Frank Stanford, Anne Carson, Gerald Stern, Raymond Carver, Charles Bukowski, Kathleen Graber, David Mitchell, Zadie Smith, Alden Nowlan, Richard Brautigan, Thomas Lux, Rachel Zucker, a lot of old Japanese haiku poets, a lot of my peers, too many to note.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I'd like to make a little film sometime. And write a book for children.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I don't call writing my occupation (I work as a maintenance worker to pay the bills). But if I devoted myself to another calling it probably would have been one of the other arts, a painter or a musician. I'm also considering going back into school to be a library technician.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I have played around with some other arts (painting and music) but it's probably the simplicity and accessibility of the materials for writing that have made it the most appealing. A pen, a piece of paper, this blob of grey matter. It costs very little and one could do it anywhere.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Probably Mary Ruefle's poetic collection of lectures Madness, Rack, and Honey. And the Swedish-Danish film We are the Best! by Lukas Moodysson. Both very alive with wonder.

19 - What are you currently working on?

Nothing, happily. Well, getting ready for a cluster of readings. I'll probably start getting back into writing again once the buzzy stuff settle down a bit. Or even take a longer break from writing and create some music. Make some new pathways in my head.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book is barely a month old at this date, so I'm in the dazed and delighted stage. But comparing my writing to my old chapbooks or online livejournal writing, I think I've become less overtly sentimental, and yet probably a bit more open to real feeling. Less cloaking. More attentive to syntax and the rhythms of the line. I think I've also allowed myself a range of new subjects I probably wouldn't have touched back then, flowers, computers, other people.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I started writing through that common angsty teenage pressure release valve. Lyrics in songs played a part too. I like how saturated in meaning some lines felt when strung together. And just being able to get in and out on a single page was appealing. I don't think I have the attention and capacity for fiction or non-fiction. Also when I was much younger, my elementary school teacher once complimented the first poem I wrote. That kind of thing goes a long way.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I've never seen my writing as a project. Most of my poems begins as messy unformed things, buried somewhere in sessions of automatic writing. If I see something that might survive, I keep working on it until it comes alive. And yes, this is after filling copious notebooks.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

My poems begin as tiny elements: an image, a phrase, a question. It grows from there. I told people I was working on a book for a while before it came out. But I was mostly only working on poems until near the end where I had to sequence. I think I still have to learn how to write books.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I really like them despite the nerves and rarely being as good as I want. It's very important for my work to connect with people. I write my poems towards that. It's such an intimate thing to have people sit quietly and listen to you, to have that trust. Especially with something as potentially volatile or bewildering as poetry. After, I want to kiss all their foreheads and say “sorry” and “thank you.”

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

Oh goodness. Well, I think I can speak only for myself. I find myself getting obsessed with certain human qualities: how we perceive things, how we try to make sense of this life. What is this sensation I have no words for? How do we get through the day? Why did that person set himself on fire? Do I want to set myself on fire on occasion? Things like that.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I imagine that a lot of poets who get to this question, pause and squirm a little. My first response is “I have no idea.” But if I pushed myself to get heady, this is what I might suggest: We all use language to make meaning out of life. And disrupting or charging that meaning-making machine, can make it spark and whir in really lovely ways. Maybe this ensures you're not taking it (or life) for granted. And we get to connect with each other on new playing fields. Even if it only happens in fleeting moments. I don't know if it is good for everyone, but it's been good for me. I think there are writers who write more overtly political and such--and that's terribly important--but I feel most of them still start with that simple function of lighting up your imagination.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Both. It really has to be a good fit or the dynamic can be very difficult. My editor was pretty hands off with my book, which was nice because I had already worked it through quite a bit with my first readers.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Doesn't it seem most good advice is what you already know, but for some reason haven't permitted yourself to follow? It's nice to hear it from another person. With writing it's probably the advice that suggests being very conscious of a reader. That and write much and often. Focus on quantity before quality.

10 -What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

If we're pretending it's my day off and somehow my 3 year old son has run off happily into the woods, you'll probably find me heading to a coffee-shop soon after breakfast and filling up a few pages my notebook. It's not very complicated. I try to (and have to often) write at different times of the day, but the morning is ideal.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

In the scenario above I have another book of poems beside me to dive into if I lose steam. In general, art, music and film helps too.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Probably an earthy post-rain garden and the smell of my wife and child. Though I don' t think I am reminded much of home unless I am home.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

All of the above, I'm sure. Music is probably the most emotional of those forms for me and probably has a direct connection to my writing more than the others.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

A handful in no particular order with apologies to the hundreds I am omitting: Bob Hicok, C.K. Williams, Dean Young, David Foster Wallace, Mary Ruefle, Matthew Zapruder, Lydia Davis, James Tate, Frank Stanford, Anne Carson, Gerald Stern, Raymond Carver, Charles Bukowski, Kathleen Graber, David Mitchell, Zadie Smith, Alden Nowlan, Richard Brautigan, Thomas Lux, Rachel Zucker, a lot of old Japanese haiku poets, a lot of my peers, too many to note.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I'd like to make a little film sometime. And write a book for children.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I don't call writing my occupation (I work as a maintenance worker to pay the bills). But if I devoted myself to another calling it probably would have been one of the other arts, a painter or a musician. I'm also considering going back into school to be a library technician.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I have played around with some other arts (painting and music) but it's probably the simplicity and accessibility of the materials for writing that have made it the most appealing. A pen, a piece of paper, this blob of grey matter. It costs very little and one could do it anywhere.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Probably Mary Ruefle's poetic collection of lectures Madness, Rack, and Honey. And the Swedish-Danish film We are the Best! by Lukas Moodysson. Both very alive with wonder.

19 - What are you currently working on?

Nothing, happily. Well, getting ready for a cluster of readings. I'll probably start getting back into writing again once the buzzy stuff settle down a bit. Or even take a longer break from writing and create some music. Make some new pathways in my head.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Labels:

12 or 20 questions,

Nightwood,

Raoul Fernandes

Tuesday, April 21, 2015

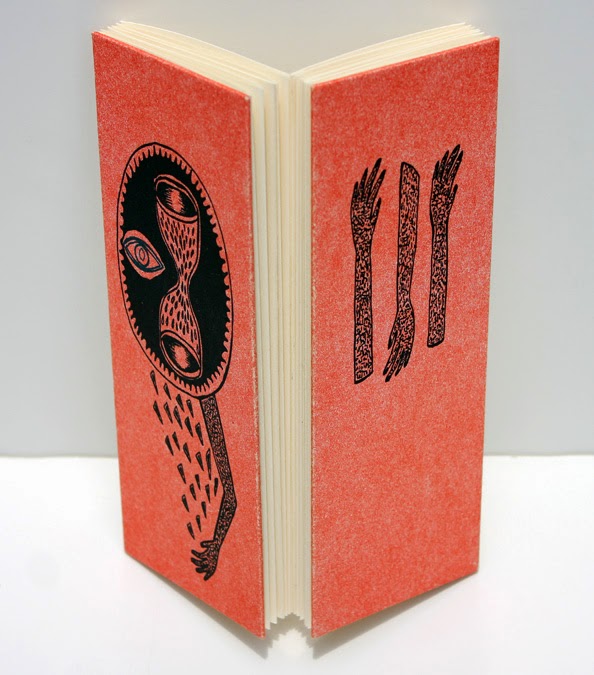

12 or 20 (small press) questions with Jared Schickling on Delete Press

Delete Press publishes work by

established and emerging poets. We ask

ourselves the question: what does it feel like to be set on fire with an

odorless accelerant? We respond by

building chapbooks that are letterpress printed and handbound. Anti-gravity ephemera is also floated.

Jared Schickling edits Delete Press and eccolinguistics, and has served on the

editorial board of Reconfigurations: A Journal for Poetry & Poetics / Literature & Culture, among others. He is also the author of several books,

recently Two Books on the Gas: Above the Shale and Achieved by Kissing (Blazevox, 2014), ATBOALGFPOPASASBIFL (2013) and The Pink (2012), The Paranoid Reader: Essays, 2006-2012 (Furniture Press, 2014) and Prospectus for a Stage (LRL Textile Series, 2013). He lives and works in Western New York.

1 –

When did Delete Press first start? How have your original goals as a

publisher shifted since you started, if at all? And what have you

learned through the process?

Crane Giamo, Brad Vogler and I started

Delete Press in 2009 when we were all living in Fort Collins, Colorado. We’ve done ten paper chapbooks since then,

and the only thing that’s really changed for us is the medium. Crane is the press’s bookmaker (I edit, Brad

is webmaster) and as his skills have crystallized the intricacies of the

objects have changed. As this has

increased the cost and amount of time between each book, Brad and I decided to

launch an e-book series. We’ve published

four titles so far. We also have our own

projects, aspects of Delete—Crane is the proprietor of the letterpress

Pocalypstic Editions, Brad publishes Opon,

an online journal of long poems and process statements, and I do eccolinguistics

in the mimeograph tradition. One thing

I’ve learned is the importance of distancing yourself from the presswork—it’s

the only way a writer will trust you and the only way to properly present

another’s work. Another is what it means

to arrive at that point where all involved will trust that someone else’s idea

is a good one, what it means to build something with people you admire.

And also this: produce, produce, produce,

be irreverent, and keep promises no matter how embarrassingly long it may take.

2 –

What first brought you to publishing?

As far as Delete is concerned, a desire to

be of service publishing great work and the belief that this could be done with

Brad and Crane.

3 –

What do you consider the role and responsibilities, if any, of small

publishing?

To change the face of literature.

4 –

What do you see your press doing that no one else is?

I think we’re unique. After all, we’re not doing what other

wonderful operations are.

5 –

What do you see as the most effective way to get new books out into the world?

To be honest, my primary concern in this

regard is to make sure we’ve made something that when read brings

pleasure. The rest seems to take care of

itself.

But certainly digital transmissions and

friendships are the most effective way to get the word out. That’s difficult too, though, as it requires

a fair degree of diligence keeping up with what’s what. Basically, I participate in various forms of

reading and listening and that natural curiosity makes the connections I

cannot.

6 –

How involved an editor are you? Do you dig deep into line edits, or do you

prefer more of a light touch?

I stay utterly faithful to the work. In the case of small press poetry, submitted

materials tend to arrive in rigidly precise form. The editing in that regard has much to do

with finding the correct shape and feel of the book object or page, or screen,

the space around the content. I

certainly have made my fair amount of text edits, though. But even there, it has tended to be in

response to some imposition of format.

I am presently editing a book in which the

next-to-last line of the manuscript needed to go. I deleted it and explained politely to the

author why it was necessary. I was right,

and the author was agreeable. It’s not

always so easy.

That’s another thing I’ve learned—more

often than not (no one is perfect), trust your editor.

7 –

How do your books get distributed? What are your usual print runs?

Editions of Delete Press paper chaps have

ranged from 40 to 120 copies. The

e-books have gotten a few hundred downloads each. 300 copies of the eccolinguistics mailer

go out periodically, for free.

8 –

How many other people are involved with editing or production? Do you work with

other editors, and if so, how effective do you find it? What are the benefits,

drawbacks?

I think I mentioned my wonderful experience

working with Brad and Crane, so I won’t say too much. Really I would just like to see them

more. We live in different parts of the

country now.

9–

How has being an editor/publisher changed the way you think about your own

writing?

Utterly.

I primarily edit my work.

10–

How do you approach the idea of publishing your own writing? Some, such as Gary

Geddes when he still ran Cormorant, refused such, yet various Coach House

Press’ editors had titles during their tenures as editors for the press,

including Victor Coleman and bpNichol. What do you think of the arguments for

or against, or do you see the whole question as irrelevant?

Well, I’m not against it in principle, but

one who goes that route needs to be very careful. The offending person’s stature in the poetry

market must be such that the ego can be overlooked. In the case of coterie, I think a shared

critical apparatus has to be there or else the cliquishness doesn’t make much

sense.

I suspect that self-publishing through

one’s own operation didn’t always carry such a stigma, when the technology and

means of distribution were more prohibitive of an over-saturated field of

publishing writers and when the aesthetics we’ve inherited were just beginning

to take shape. Perhaps it is that the

vast good and cheap publishing opportunities for poets today means the

expectations for model behavior have changed.

11–

How do you see Delete Press evolving?

I don’t know. To be honest, Crane’s bookmaking abilities

have reached a point where we are reassessing what the chapbook line should

be. I suspect that we will also be doing

full-lengths in the near future. Brad is

pondering a new website. Delete Press

has changed and will change again, I know that.

12–

What, as a publisher, are you most proud of accomplishing? What do you think

people have overlooked about your publications? What is your biggest

frustration?

I’m proud that we’ve sold out of most everything. That might sound superficial, but it’s

not. The generous response from readers

has helped confirm my faith that, contrary to a popular belief, people actually

do read poetry.

But you have to be realistic about it. I wouldn’t say we’ve been overlooked—we’ve

been too busy making and publishing to notice in any case. You have to be tactical in your methods and

output depending on the work you are publishing. And you have to be willing to accept

anonymity.

For me the frustration is with trickle-down

poetics. I’m not looking for laurels but

I wish the embalmed would get out of the way.

I just read a rather smug response by Ron Silliman to the identity

politics happening in poetry lately. The

gist of his blog screed is that humankind is headed for a cliff of epic

proportions, so there’s no sense getting riled up. Plus, he says, if the targets are

institutional then they’re misguided.

Hell, even the police are our friends—verbatim! We’re just too far gone for any of that to

matter, says Ron Silliman. The problem

is that unless he’s rapture-bound, which he very well may be, who can say, then

Silliman is as stuck here in the only place we got as anyone.

The life of poetry and of literature is

always small press. Always. Chris Fritton printed these wonderful

broadsheets for the Buffalo Small Press Book Fair that are tacked to my office

walls: “Small Press / Everything for Everyone Nothing for Ourselves.” The words are Mike Basinski’s, or so I hear. An original Basinski gifted me is tacked next

to one of the broadsheets. I kind of live

according to that advice.

13–

Who were your early publishing models when starting out?

Frankly, I didn’t have any. I read voraciously and saw all manner of

things. But later on, dirty mimeo, Fuck

You, The Marrahwanna Quarterly, the Aldine Press, Grove, stuff

like that.

I did learn a great deal from Stephanie G’Schwind at the Center for Literary Publishing at CSU, where I interned, and

from David Bowen of New American Press, whose Mayday Magazine I helped

launch (issues 1 and 2). I learned a

great deal about what not to do as an editor and publisher at Alice James Books. That shouldn’t be taken the wrong

way, as AJB is very good to their authors and their own venerable history

doesn’t need me.

14–

How does Delete Press work to engage with your immediate literary

community, and community at large? What journals or presses do

you see Delete Press in dialogue with? How important do you see

those dialogues, those conversations?

Well, at one point I think Compline, LittleRed Leaves, Punch Press, and Delete considered getting a small corner of

AWP. That was maybe five years ago, I

don’t remember. I still dig what those

three are doing.

But honestly we at Delete are

omnivores. I know I am. Ugly Duckling Presse is stellar, of course,

and I am particularly fond of their translation series. michael mann’s unarmed is a powerful

little journal. One of my most cherished

possessions is a tiny, nondescript, side-stapled bit of ephemera from Luc

Fierens and François Liénard, PAPER WASTE SHOOTING! Boaat Press’s Some Simple Things Said By and About Humans by Brenda Iijima is a book whose physicality furthers

what’s there in the poem. Projective Industries, Further Other Book Works, Cuneiform Press—there are some master

bookmakers out there, all specializing in poetry.

15–

Do you hold regular or occasional readings or launches? How important do you

see public readings and other events?

We don’t organize launch readings or sell

wares at book fairs as we don’t have any stock to speak of. All the books are gone. I’ve organized readings, but not for

Delete. Readings are very important.

16–

How do you utilize the internet, if at all, to further your goals?

We advertise on the Internet and otherwise

read it. Reading is essential to a

publisher, for all the obvious reasons and more.

17–

Do you take submissions? If so, what aren’t you looking for?

Generally speaking, yes. We are fluid and keep ourselves open to what

comes in. We like adventurous work and

we know we want it when we see it. We

are in every way an experimental bunch.

We also solicit most projects that we end up taking on.

18–

Tell me about three of your most recent titles, and why they’re special.

PORCHES by

Andrew Rippeon

Dancing in the Blue Sky: Stories by Geoffrey Gatza

ROPES by W.

Scott Howard and Ginger Knowlton

All of these literary works advance an

internal poetics while stimulating the senses.

Each of them invokes their respective traditions while managing to

transcend lineage and enter into dialog with a contemporary moment.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)