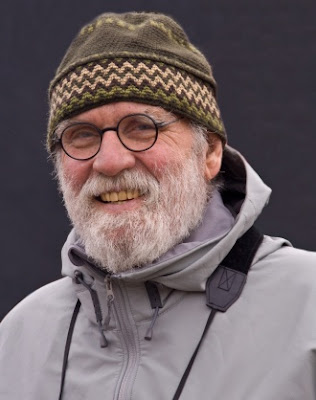

Graeme Gibson is the acclaimed author of Five Legs, Perpetual Motion, and Gentleman Death. He is a past president of PEN Canada and the recipient of both the Harbourfront Festival Prize and the Toronto Arts Award, and is a member of the Order of Canada. He has been a council member of World Wildlife Fund Canada, and is chairman of the Pelee Island Bird Observatory. He lives in Toronto with writer Margaret Atwood.

Graeme Gibson is the acclaimed author of Five Legs, Perpetual Motion, and Gentleman Death. He is a past president of PEN Canada and the recipient of both the Harbourfront Festival Prize and the Toronto Arts Award, and is a member of the Order of Canada. He has been a council member of World Wildlife Fund Canada, and is chairman of the Pelee Island Bird Observatory. He lives in Toronto with writer Margaret Atwood.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Five Legs, which was my first book, changed my life because in desperation I had started another novel while it was being rejected in sequence by a Canadian, an English, and finally by an American publisher before the House of Anansi took it on. Then when Five Legs was published and sold out the first printing in less than two weeks, I experienced the seductive spasm that accompanies notoriety, and my fate was therefore sealed. I was going to be a writer.My current work, The Bedside Book of Beasts, obviously differs in form and style from the novels. A companion to The Bedside Book of Birds (2006), it feels very different, if only because my preoccupations are a very long way from those of the youth who started out writing novels. Back then I don’t think I’d have understood E. O. Wilson’s remark that “The natural world is imbedded in our genes and cannot be eradicated, or Thoreau’s “In wildness is the salvation of the world.”

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?The story I felt compelled to explore demanded the form of a novel. Anyway, my early attempts at poetry were preposterous.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I worked on my first novel for almost ten years and all my fiction took forever to finish. Most of my own re-writing and editing was done on each page before I went on to the next one. It was a bit laborious, but there you are. It was what I did.4 - Where does a book usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Whenever I discover an emerging project I know it will be a book -- assuming, of course, I finish it. In the more than thirty years I abandoned at least four manuscripts. With two of them I was well into the second year before I let go.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

On the whole, yes, I do enjoy readings, partly because when I’m writing I try to hear my sentences and paragraphs. The voice is somehow central to my prose. Margaret Laurence once told me that she didn’t understand what to do with my second novel, Communion, until she’d heard me read from it.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

My non-fiction books have both theoretical and practical concerns about how we humans have related to the natural world, and what we have done to it in the process of feverishly trying to escape nature. For me, there’s no shortage of current questions; there are, however, a worrisome lack of answers.

7 - What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

To be his or her own best and most honest voice.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

This largely depends on whether I think the editor has understood what I was doing, or trying to do.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Write for the book and edit for the reader.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (fiction to non-fiction)? What do you see as the appeal?

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (fiction to non-fiction)? What do you see as the appeal?

The appeal is in the material, in the intent, not in the form. When I was writing novels I never thought that I’d write anything else. I did manage to eke out one short story, Pancho Villa’s Head, but it took almost as long to complete as my novels did. I’d like to have written more but they just weren’t there.

I turned to non-fiction because I had resolved the problems that fiction can address and dramatize, at least for me. The miscellanies give me scope to learn, to explore and try to celebrate the deeply moving truth of creatures that are truly wild.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?I’m not good at routines. The day begins early, but slowly.12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Saint Augustine is supposed to have said solvitur ambulando, it is solved by walking. That may be true, however sometimes you have to walk for quite a while.

13 - What do you really want?

Possibly an answer to this question.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Books may come from books, indeed they probably do as a form, but the motives, thoughts and feeling that urge one to write often rise from deep-seated shadows within a whole life.

My current book, The Bedside Book of Beasts, emerged from my desire to learn more about alpha predators and their prey. They are central to us, and to our understanding of our place in nature, because the primal fact of hunting and/or being hunted, and the inescapable demands of hunger, have largely defined animal life on earth, and are undoubtedly among the key engines driving evolution. We are what we are largely because we must eat -- and have lived in danger of being eaten.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

The Bedside Book of Beasts, and my Bird book, are both wide-ranging miscellanies, with texts and images from scores of others who have explored and celebrated non-human nature and our relationships with it. As a result it is really a body of work, a genre, a way of seeing if you will, that is fundamentally important to both my work and to my life.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Learn to waltz gracefully in order to delight my partner.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I used to dream that I’d escape to sea.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

When I started writing all other alternatives seemed either impossible for me, or else unspeakably dreary. Moreover it seemed clear that I had to write my first book, Five Legs, in order to set some psychic records straight.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

The last “great” book I read was The Peregrine by J. A. Baker. It is an extraordinary thing, and hard to describe. It is almost as if Baker wanted to become a Peregrine. There’s something shamanistic in his quest, it evokes that ancient magic when souls moved effortlessly between animal and human bodies.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I’m trying to catch up on the melancholy pile of busywork left undone by my preoccupation with the Bedside Book of Beasts.

12 or 20 questions (second series);

Graeme Gibson is the acclaimed author of Five Legs, Perpetual Motion, and Gentleman Death. He is a past president of PEN Canada and the recipient of both the Harbourfront Festival Prize and the Toronto Arts Award, and is a member of the Order of Canada. He has been a council member of World Wildlife Fund Canada, and is chairman of the Pelee Island Bird Observatory. He lives in Toronto with writer Margaret Atwood.

Graeme Gibson is the acclaimed author of Five Legs, Perpetual Motion, and Gentleman Death. He is a past president of PEN Canada and the recipient of both the Harbourfront Festival Prize and the Toronto Arts Award, and is a member of the Order of Canada. He has been a council member of World Wildlife Fund Canada, and is chairman of the Pelee Island Bird Observatory. He lives in Toronto with writer Margaret Atwood. 10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (fiction to non-fiction)? What do you see as the appeal?

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (fiction to non-fiction)? What do you see as the appeal?

1 comment:

rob,

in my humble opinion the greatest Canadian (correction: North American) novel written is 'Perpetual Motion'. Second perhaps only to Buckler's "The Mountain and the Valley".

This guy's a living legend! Lucky you if you know him.

Post a Comment