OFFICE HOURS

They say, I want to know

how to do better. I am applying to medical school next year, so I need to make

sure I have perfect grades. I was wondering, they say, if we could go over the

next essay assignment. I know this paragraph doesn’t make sense. I don’t know

what point I’m trying to make. I ask them, What are you really trying to say? They

say, I am still adjusting to my medication. They say, Last week I went to the

emergency room. Do you know what a panic attack is? I tell them that I think I do.

They say, I feel like I have to choose between feeling stupid and feeling

scared all the time. I say, I feel like we can figure out this paragraph. I’ll

ask you some more questions and then we’ll figure out what you were trying to

say.

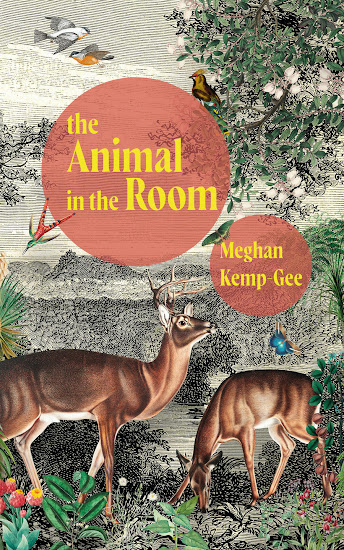

There are some interesting formal shifts in poet Meghan Kemp-Gee’s full-length poetry debut, The Animal in the Room (Toronto ON: Coach House Books, 2023). There is something in the way she works her lyric narratives from line-breaks to prose poems, attempting to feel out her own sense of formal opportunity, syntax and shape. “Through her syntax and diction,” she writes, to open the prose poem “THE THESIS SENTENCE,” “the author explores her main theme in a clear and effective way. Through the use of rhetorical devices including metaphor and repetition, the writer emphasizes her argument. Throughout this poem, the meaning is reflected by the form in several ways. In this text, the author has some questions and she asks them using various rhetorical techniques and narrative strategies.” Throughout The Animal in the Room, there are poems that sparkle with inventiveness and wit, as she composes a bestiary of sentences and syntax. Each of her animals, as well as her sentences, retain their wildnesses, even while set up against a particular element of constraint or restraint. Kemp-Gee’s structures do seem exploratory, as she attends and examines her lyric with a careful deliberateness, one that can’t easily be situated. Holding a back cover quote by poet Sue Sinclair suggests a particular lyric formality that Kemp-Gee’s poems might include as a strain, but her overall experimentations eventually contradict, as the pieces here are more interested in structural differences and staggerings of syntax than any specific adherence to narrative form. Instead, her formal engagements, specifically through the prose poems that tether the collection together across a variety of forms, hold shades of the work of Rosmarie Waldrop, Anne Carson or even Lydia Davis:

TEACHING COMPOSITION

I compare a satisfying sentence to the feeling of kicking somebody as hard as you can, square in the chest. The kid in the back row asks, Have you actually done that?

This

is very much a book of structures, of sentences; writing of animals and dreams,

and the dreams of animals: the brontosaurus, the giant pacific octopus, the

Vancouver Island marmoset and the Greenland shark, among others. “I have a

question / for the ticks who dream / about being wolves. / My question concerns

/ orchids and the end / of the world,” she writes, to open the poem “THE BLOODSUCKER,”

“concerns / the colour blue and /rare diseases.” This book suggests some

remarkable things are still to come from Meghan Kemp-Gee; I, for one, am very

much looking forward to seeing what she does next.

No comments:

Post a Comment