It’s 2022. The world is ending, but how fast? and for whom? and what do we have to pay to keep it around for a little longer, just until we get that one last day with our kids, last hour of rolling around in bed (with or without someone else in the bed), last pancake, last walk, last book we love to read?

Good Grief, the Ground might be one

of those last books: light enough to come back to us, and heavy enough to stay

with it. It certainly feels “like the end of something” to Margaret Ray, who is—or

writes as—a white, adult, American woman with Florida roots and a presence in

New Jersey now, a teacher still close to the epoch of fortunate teens, for whom

“no one/ is dead yet,” teens full of hunger, “ready to go somewhere.” What do we

do with that hunger if we grow up, if we realize that some people are hungry

for us, that some people are never full, that we too have needs we mistake for

wants and vice versa, that two contradictory things can be true? (Stephanie

Burt, “FOREWORD”)

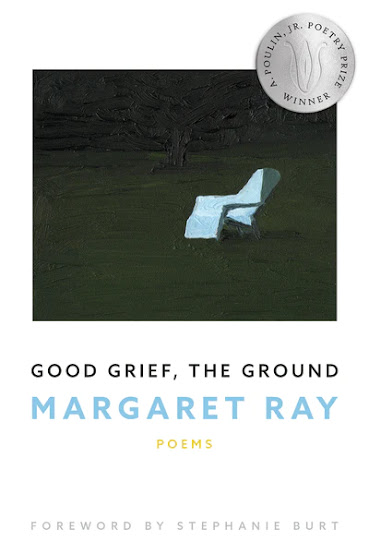

Winner of the 21st annual A. Poulin Jr. Poetry Prize, as selected by Stephanie Burt, is New Jersey-based poet Margaret Ray’s full-length poetry debut, Good Grief, the Ground (Rochester NY: BOA Editions, 2023), a book that holds together as a selection of lyric narrative rolls and extended rushes. Offering portraits of small town urban/suburban teenhood, Ray crafts urgent poems that strike through memory as they pour out sentence accumulations and lines that see no end until they finally, eventually, do. “I want to tell you about two events / that form the cusp of a childhood:,” she writes, near the opening of the poem “Expulsion Lessons but Replace the Garden with a Swamp,” “One thing happened to me (alone), / and one happened (on TV) to America / after it happened (in private) to a pair // of people I’ll never meet.”

I’m intrigued at her poem-recollections and warnings that speak of the dangers and drama of growing up and remaining, somehow, alive; writing on dark paths, dark corner and the crevices of youth, violence and small towns. “Think of how skin / glues itself back together after you slice your finger / chopping an onion,” she writes, as part of the poem “Enough,” “Not scar as metaphor no / how long it takes How quick the knife / The problem with children is that if you’re lucky // they grow up [.]” Or the incredibly striking “Reader, I Married Him,” riffing off the infamous quote from Charlotte Brontë’s novel Jane Eyre (1847), that references youthful digression, hints at shades of domestic violence, and plays a number of quick-turns and insights, including: “I threw the book at him and slammed / the door on the way out. In a poem I can leave / when I should have.” From the hard lessons of experience and distance, Ray writes generously of the hopes that youth might hope and how inexperience can blindside even the sharpest mind. “It was later, later,” she writes, as part of “Expulsion Lessons but Replace the Garden with a Swamp,” “once I turned the memory off its shelf / and turned it over again, only / once I knew what he’d been doing / while he looked at me, that’s // when I was no longer a child.”

There’s

a way that the structure of her collection feels akin to a sequence of

calls-and-response, a back and forth of a section-cluster of poems followed by

a single, stand-alone lyric, a second section-cluster followed by a further single,

stand-alone lyric, and so on, offering a quartet of such pairings to make up

the larger structure of what becomes Good Grief, the Ground. The short pieces—“Wanda

is a Particle Physicist,” “Wanda Vibing,” “Wanda in the World” and “At a Distance”—almost

exist as a kind of connective tissue that threads through the collection and

holds it together into a larger narrative. As the first of these poems end: “Wanda

looks back / at the traces her particles have left, // moving through a field.”

It is interesting how the character “Wanda” somehow floats at a distance from

the main action of the book, somehow tethered but unaffected, or even above,

whatever may have occurred before. There is only what is happening now.

No comments:

Post a Comment