FUGUE 11 | HELLO, MY SLEEP

Hello, my sleep, my dawn

thing

milk welling in the eyes

of night—if you should

let me

if 6 am should slice this

cannister, carry the egg

of this thought

in its mouth through the

colliding

fonts of sensoria—the eyes

of night

open, it all leaks out

this sleep just a plane

on the polyhedron: sleep,

our sleep

rising over the world (“FROM

FUGUE & FUGUE”)

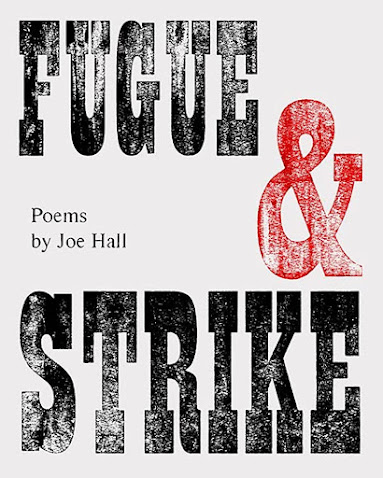

The fourth full-length collection by Buffalo, New York “poet, critic and junk bookmaker” Joe Hall, following Pigafetta Is My Wife (Boston MA/Chicago IL: Black Ocean, 2010), The Devotional Poems (Black Ocean, 2013) and Someone’s Utopia (Black Ocean, 2018) is Fugue and Strike: Poems by Joe Hall (Black Ocean, 2023). Fugue and Strike is constructed out of six poem-sections—“From People Finder Buffalo,” “From Fugue & Strike,” “Garbage Strike,” “I Hate That You Died,” “The Wound” and “Polymer Meteor”—ranging from suites of shorter poems to section-length single, extended lyrics. Hall’s poems are playful, savage and critical, composed as a book of lyric and archival fragments, cutting observations, testaments and testimonials. “[…] to become a poet / is to kill a poet,” he writes, as part of the poem “FUGUE 6 | JACKED DADS OF CORNELL,” “cling to a poet / in the last hour, before slipping into the drift / atoms of talk bounce in cylinders down Green St, predictive tongue / in the aleatory frame stream of vaticides […].”

Throughout the first section, Hall offers fifty pages of lyric lullabies and mantras towards a clarity, writing of sleep and machines, fugues and their possibilities. “each poem / an easter egg,” he writes, as part of “FUGUE 40 | DEBT AFTER DEBT,” “w/ absence inside and inside absence / you are hunger, breathing this time and value / particularized into mist, you are there, at the end / of another shift […].” The second section, “Garbage Strike,” subtitled “BUFFALO & ITHICA, NY, USA / JAN-MAY 2019,” responds to, obviously, a worker’s strike that the author witnessed, and one examined through a collage of lyric and archival materials from the time. Echoing numerous poets over the years that have responded to issues of labour—including Philadelphia poet ryan eckes, Winnipeg poet Colin Brown, Vancouver poet Rob Manery and the early KSW work poets including Tom Wayman and Kate Braid—Hall’s explorations sit somewhere between the straight line and the experimental lyric, attempting to articulate a kind of overview via the collage of lyric, prose and archival materials. There is something of the public thinker to Hall’s work, one that attempts to better understand the point at which capitalism meets social movements and action, all of which attempts to get to the root of how it is we should live responsibly in the world. There’s some hefty contemplation that sits at the foundation of Hall’s writing. Or, as he writes near the end, to open “POLYMER METEOR”:

George Oppen wrote in “Discreet Series,” “Rooms outlast you.” Pithy. And also indicative of a relation to time that is modest, sobering. We die, apartments go on. Their floors get scratched by someone else’s chairs. Their vents fill with the dust of someone else’s life. But those rooms also go, demolished to make way for some other, pricier structure. Or those rooms are split open to moisture and creatures seeking shelter in a zone of divestment. A frame of time in which things live decades to centuries.

Through notes on the poem/section included at the back of the collection, Hall writes that “In terms of the content of Garbage Strike, the researcher must now sweep up after the poet. Garbage Strike is meant to be suggestive; it grew from a small archive of peoples’ insurgent imagination in relation to waste. It’s not thorough historical scholarship, and I remain a student of the subject.” Further on, his note ends:

As recent scholars like Charisse Burden-Stelly have persuasively theorized the operations of racial capitalism in the modern US context, new directions for the work open up. For instance, to seek more on-the-ground facts about these struggles and to understand their relation to the operations of racial capitalism through the contexts those facts provide. To learn to recognize how particular individuals and institutions translate the dynamics of racial capitalism into distributions of waste, hierarchies of labor, and extraction of profits—and the multifarious ways people get together and fight back.

No comments:

Post a Comment