My mother said when I was born, she was afraid.

Women born in the Year of

the Tiger are fabled as

too much in their own

story. They’re risk-takers in

this world, which typically spells feminine ruin.

She laughs often at her small monster, leaping again into dark.

She was also afraid of

the fourth scar;

they said she’d be ripped

apart between white walls.

This country is not for the faint-hearted; I will wear it.

This is the sentence in my body, decorated.

I cannot (not) take it

off. (“On Passing”)

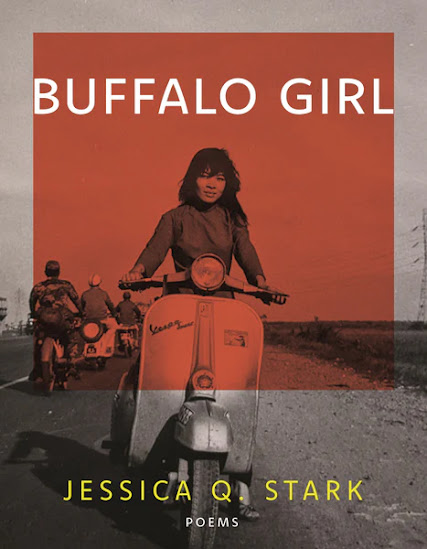

Jacksonville, Florida-based poet and editor Jessica Q. Stark’s second full-length poetry collection, following Savage Pageant (Birds LLC, 2020) [see my review of such here], is Buffalo Girl (Rochester NY: BOA Editions, 2023). As the press release offers, Buffalo Girl writes the author’s “mother’s fraught immigration to the United States from Vietnam at the end of the war through the lens of the Little Red Riding Hood fairy tale.” As Stark offers at the offset of the poem “Phylogenetics,” “When it began isn’t clear, but isn’t it obvious that we always had a knack / for stories about little girls in danger?” Stark examines, through collages of text and image, an articulate layerings of breaks and tears, intermissions and deflections; examining how and why stories work so hard to remove female agency. “In this body is my mother’s body,” she writes, as part of the extended “On Passing,” “who paid the fantastic price in / fairy tales written mostly by men.” She offers elements of her mother, including pictures of her mother repeatedly on a scooter, providing a curious echo of Hoa Nguyen’s A Thousand Times You Lose Your Treasure (Wave Books, 2021) [see my review of such here], a collection that explored her own mother’s time spent as part of a stunt motorcycle troupe in Vietnam. “You can paint a woman // by the river bank,” Stark writes, to open the poem “Con Cào Cào,” “but // you can’t ever imitate // a sound, fully. This story is // not simple.”

Playing off the traditional American folk song “Buffalo Gals,” Stark tweaks the lyrics, offered as part of the poem “The Old Man in the Tree,” which ends: “And an old man somewhere high // was feeling satisfied with / his meal and his lodging and // he sang: // Oh, Buffalo Girls, // won’t you come / out tonight, // come out tonight, / come out tonight, // Oh, Buffalo Girls, // won’t you come out tonight, // and dance by the / light of the moon?” Stark offers multiple images and tales of her mother blended with flora and fauna, as well as the image of a figure, often male, and usually obscured or erased through that same foliage; hidden, suggesting a wolf in the wild. “History makes little bundles out / of the unthinkable,” she writes, as part of the title poem, “young boys carve // three-foot breasts // to keep your story otherworldly and / ridiculous; a crisp blade slips // from view [.]”

Buffalo Girl writes out threads of Stark’s mother’s history, and examines the cultural fascination with stories of innocent girls and bad wolves, writing a fairy tale framing multiple versions of Little Red Riding Hood, one across another. In many ways, she writes her way into being; of herself into that history and lineage of her mother, from one culture into another, and a lineage that now includes her own son. Attempting to navigate the complications of movement and wolves, determination and difference, Stark’s lyrics explore her mother’s history to place her mother on solid ground, so that she, too, might be able to find ground, and come to terms with her mother’s stories. “For years I tried on different stories about my body,” the poem “On Passing” begins, “to use the body as a rinsing husk. // Language here is also a delicate peapod, a shell / that forms the world and its fantastic borders. // For years I ignored the sentence in my body. // Who came and who went—a blank ledger.” Stark may begin with Red Riding Hood and a myriad of wolves, encountered, fought and avoided, but this is a collection through which she explores and discovers what her mother taught her, whether through example or presentation, as well as what her mother is actually made of, despite violence, trauma, loss and what wolves are capable of; and what her mother is made of is considerable. Or, as the poem “Near-Death Experience” ends:

How the dark

imprints a tiny tattoo

in the shape of life’s

physical humor. I talk

my mother into

visiting my new home

in Florida. I will

see her soon.

She will say

how much

closer death

is to her now. I have

plans. I will pick

her up in an automobile

that’s painted red.

I will reserve a day

for regarding the

big, vast sea

near which

I’ve made my home.

No comments:

Post a Comment