On finishing my translation of Eingedunkelt, I was startled to discover the 11 poems comprising this work required a draft of over 100 pages. Rereading these materials, I came to understand that a response in English to Paul Celan’s poetry in German necessitates a material approach. The poem’s word-materiality in English first must parallel the word-materiality in Deutsch.

What do I mean by this? I

propose considering this parallel materiality as a kind of alchemical Landschaft

or Landscape. One wherein, amid its territory, we may inscribe Stein as

Stone – and as a result of the difference between words, we may be

granted a glimpse of their glyphic (and lithic) associations as anomalies: a

chrysopoeia through which the under-poem may announce itself. (afterword, “ON

TRANSLATING PAUL CELAN”)

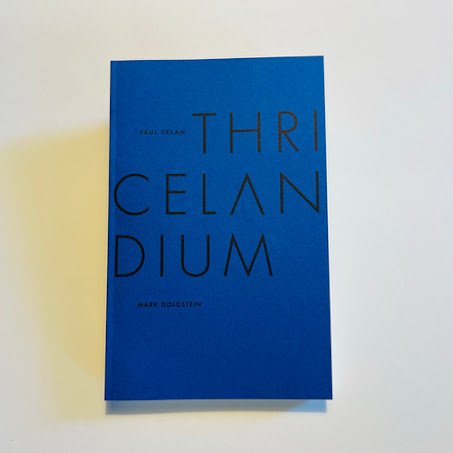

Further to Toronto poet, editor, publisher, translator and critic Mark Goldstein’s explorations through the work of Romanian-French poet Paul Celan (1920-1970) is Thricelandium (Toronto ON: Beautiful Outlaw Press, 2024), translated by and with a hefty introduction and even heftier afterword, “ON TRANSLATING PAUL CELAN,” by Goldstein. Thricelandium is but one step in a much larger trajectory through Goldstein’s thinking around Celan’s work, with other elements including: his poetry collection, Tracelanguage: A Shared Breath (Toronto ON: BookThug, 2010) [see my review of such here]; his collection Part Thief, Part Carpenter (Beautiful Outlaw, 2021), a book subtitled “SELECTED POETRY, ESSAYS, AND INTERVIEWS ON APPROPRIATION AND TRANSLATION” [see my review of such here]; as publisher of American poet Robert Kelly’s Earish (Beautiful Outlaw, 2022), a German-English “translation” of “Thirty Poems of Paul Celan” [see my review of such here]; and as curator of the folio “Paul Celan/100” for periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics, posted November 23, 2020 to mark the centenary of Celan’s birth. It has been through the process of moving across such a sequence that I’ve begun to appreciate the strength of Goldstein as a critic, offering a thoroughness and detail-oriented precision to his thinking, working to articulate his approach to the material and his translations of such, that seems unique, especially one focused so heavily on the work of a single, particular author. Honestly, I’m having an enormously difficult time not reprinting whole swaths of his stunningly-thorough introduction, which deals with, among other considerations, Goldstein’s approach to the translation and how Celan’s work helped him develop his own writing. As Goldstein wrote as part of his “A Prefatory Note:” for the “Paul Celan/100” folio:

I came to the work of Paul Celan in my 20s through the common entryway of his poem Todesfuge [Death Fugue]. I suspect that I first encountered it in anthology — likely either in Jerome Rothenberg’s translation found in Poems for the Millennium or in John Felstiner’s translation as it appears in Against Forgetting: Twentieth Century Poetry of Witness.

In each case I was startled by Celan’s power of expression, and as a Jew, I obsessed over his early use of the imagery of the Shoah. In time, as I read through his books, I began to develop an ever-expanding sense of their territory. Moreover, as the writing neared its terminus, I came to recognize my estrangement with it too — one born from its profound and compelling angularity.

I’ve long been intrigued by Goldstein’s long engagement with the work of Celan, as deep and rich as his engagement with the work of Perth, Ontario poet Phil Hall, from Beautiful Outlaw having produced multiple chapbooks and books by Phil Hall, to the recent ANYWORD: A FESTSCHRIFT FOR PHIL HALL, eds. Mark Goldstein and Jaclyn Piudik (Beautiful Outlaw Press, 2024) [see my review of such here]. On the surface, at least, there seems far more affinity between the work of Celan and Hall than the two life-long focuses of Ottawa poet, publisher and bibliographer jwcurry’s writing life, bpNichol and Frank Zappa, although either of these parings (or trios, really) would make absolutely fascinating theses by some brave academic at some point.

Across three poem-sequences—“ATEMKRISTALL · BREATHCRYSTAL,” “EINGEDUNKELT · ENDARKENED” and “SCHWARZMAUT · BLACKTOLL”—there is a lovely contrary and delicate quality to these poems, offered both in the original German alongside Goldstein’s translation. The language swirls, moving in and out, and through, blended and perpetual meanings that become clear as one moves through, holding a firm foundation of clarity by the very means of those swirlings, those gestural sweeps. As Goldstein’s translation offers, early on in the first sequence:

Etched in the undreamt,

a sleeplessly

wandered-through breadland

casts up the life-mount.

From its crumb

you knead our names anew,

which I, an eye

in kind

on each finger,

feel for

a place, through which I

can awaken to you,

a bright

hungercandle in mouth.

No comments:

Post a Comment