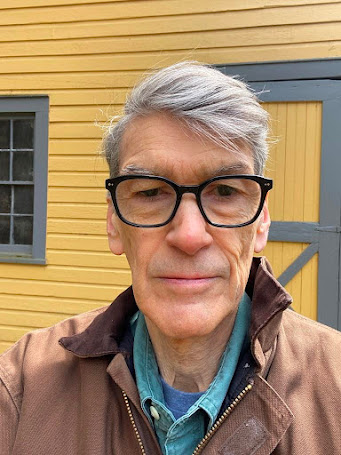

Douglas Crase is a poet and former MacArthur fellow who made his living as a speechwriter. His first book, The Revisionist, was named a Notable Book of the Year 1981 in The New York Times and nominated for the National Book Award and National Book Critics Circle Award. His collected poems, The Revisionist and the Astropastorals, was a Book of the Year 2019 in the Times Literary Supplement and Hyperallergic. His collected essays, On Autumn Lake, was noted for its “rare intimacy” and awarded a starred review by Kirkus in 2022. Crase lives with his husband in New York and Carley Brook, Pennsylvania.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

The interval between the writing and the publication was so lengthy the emotional change had already occurred. One thing you learn from a first book, however, is that it matters to people you never envisioned and doesn’t matter to those you secretly hoped to persuade. This can be interesting. It changes the way you think about fellowship, which is bound to make a difference in your work.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

Poetry came to me, twice. The first, before I was old enough to read, was when my grandmother read to me “The Song of Hiawatha.” The magic of it transformed her voice and it seemed she herself was Nokomis, daughter of the moon, the grandmother of the poem. The second was when my great aunt gave me a copy of Leaves of Grass. By then I was eleven. I'd written a would-be novel about a boy and his horse, so my aunt probably thought I needed an example of authentic literature. The magic this time transformed the farm where I was growing up, made it an arm of the cosmos, a proxy for Whitman’s cosmic democracy. Fiction couldn’t compete with that kind of power.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

If it’s a poem you don’t know when it started; you only know when it comes to the surface. But if it’s an essay it takes forever because you do know when it started. I am not a believer in first drafts. If there aren’t fifteen or twenty drafts the thing hasn’t been written.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Again it depends. If your question is about poems, they begin as inchoate problems. Sometimes, after they’ve been hanging around as a kind of hum, they introduce themselves by title. But in the case of “pieces” the problem is present at the outset, like an assignment, so the solution ends up most likely as prose. My ideal would be to combine the two in a single, unimpeded way of life.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

They are apples and oranges. The audience when you write and the audience when you read are on different planets. You desire them both.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I wish writers could position the new cosmology, post Hubble, Heisenberg, and Higgs, in a language that makes it inescapably natural. It should render the fear merchants ludicrous, as we know they are.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Well, this sounds like a tautology but the role of the writer is to write. Everything else is application and puts off the muse.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

When I wrote speeches for a living I got accustomed to the many edits you might need to satisfy a client. You couldn’t afford to resent them. Plus, they focus you on the destination of your words. So I learned to edit myself ahead of time. But the outside editing of an essay is rare in my experience, and of poems it just doesn’t happen.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

The most memorable advice came from John Ashbery, when I had complained of being nervous about doing something. “I always find you’re saved by your own charm,” he said gently. Imagine the power of that, if you could put it in practice. It certainly worked for him.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to essays)? What do you see as the appeal?

Too easy, and as I said earlier my ideal would be to make them the same. Freedom and accuracy at the same time.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Though I’d love to be among the writers who work at a certain time of day, for their whole lives, this would be a luxury that doesn’t always fit your responsibilities. For poetry, the best would be to procrastinate all day and start writing at four in the afternoon, trusting someone else to have dinner waiting at ten, or whenever I chose to reappear. For an essay I’d want to start after ten and write until five or six a.m. Life, obviously, is apt to intervene.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I like to go to a place, even if it’s just outside, and look at it. Emerson said we are never tired as long as we can see far enough. Oatmeal cookies help too.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Silage, manure, freshly mown alfalfa; or all at once.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

McFadden was right. Of course the other four—nature, music, science, and art—are all motivational too. What’s left? I guess I’d add love and the strange goads that come with it: anger, humiliation, guilt, desire, and care. They may not seem like forms but they are.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

When I began to write speeches for a living I met an older speechwriter, Joe Brickley, who had a lasting impact. It’s past time to acknowledge him. From Joe one learned to be amused by the tricks a writer employs, the play-by-play that gets you from beginning to end. In particular he taught me to recognize as egotism the kind of writing that itemizes every alternative. He called it the “on-the-other-hand-he-wore-a-glove” school of writing, where you balance everything and say nothing. That liberated my poetry as much as prose.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Become proficient with a chainsaw. There are a lot of trees here and the dead ones fall across the paths and get in the way.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

One of those aptitude tests they gave in high school, the Kuder Preference Test, said I should have a career in agriculture.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

In law school I hated the drudgery. I took a couple outside writing jobs and discovered in their case I almost liked the drudgery. If I was writing a poem you could even say the drudgery kept me in thrall. So it took too long, but eventually I dropped out of law school and looked for a way to write.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I read recently a terrific first book, Irredenta, by the poet Oscar Oswald. His project, apparently, was to re-purpose the pastoral poem for a decolonized, climate-threatened, politically uncertain North America; and he succeeds in ways I couldn’t have imagined. So I looked again at the great original, the Idylls of Theocritus, which I honestly didn’t remember very well. It turns out, if we ever thought pastoral was precious and irrelevant, we couldn’t be more wrong. As Oswald says in an essay for Lit Hub, there is no pastoral without threat of evil, doubt in our beliefs, or “rebuke of their slack power in the face of calamity.” From Theocritus it’s an inevitable step to the Eclogues of Virgil, Leaves of Grass, and Irredenta. They amount to an epic more durable even than film.

20 - What are you currently working on?

The answer to that is always the same: It’s too early to tell.

No comments:

Post a Comment