My review of Montreal poet Domenica Martinello's second full-length poetry title, Good Want (Coach House Books, 2024), is now online at Chris Banks' The Woodlot. See my review of her debut, All Day I Dream About Sirens (Coach House Books, 2019), here.

Friday, May 31, 2024

Thursday, May 30, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Concetta Principe

Concetta Principe is a writer of poetry, fiction and creative non-fiction, as well as scholarship on trauma and literature, living with a disability. Her current poetry collection, Disorder, is coming out with Gordon Hill Press in the spring of 2024. Her most recent creative non-fiction project, Discipline N. V: A Lyric Memoir, was published by Palimpsest Press in 2023. Her poetry collection, This Real was longlisted for the Raymond Souster Award in 2017 and her first book of poetry, Interference won the Bressani Award for poetry, 2000. She edited a special issue “Lacan Now” for English Studies in Canada. She teaches at Trent university.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Interestingly enough, it was my second book, a collection of prose poems, that changed my life. For one, there was no dread in creating a 'second book" since I'd already had it drafted when my first book, a novella, came out. More than that, the poetry project actually outshone the first book, winning an award for best poetry.

Writing the novella changed my life because the experience of finishing a book length project was harrowing. I was writing it for my final MA project. I had an on-going conflict with my first mentor which involved me second guessing every move. A second mentor came to rescue me and helped me complete the draft to finish my degree. But overall, the drafting of this book was not enjoyable creatively: not the first draft nor subsequent drafts of which there were several. But in the process of writing, I came to see the value of being committed to the craft. I had some brilliant moments, some revelations, some creative break throughs, which kept me going. And when the fiction was getting me down, I'd write poetry. So I would unstick myself from creative blocks by toggling between genres. The poetry I wrote during the writing of the novella became my second book.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

Thinking back to my first writing experiences, I wrote in all genres, but ended up writing prose poems for the most part, inspired by Stein's Tender Buttons. I first discovered her at the age of 10. The reason that i end up writing prose poems is because I have a storytelling drive in me. The emotional spark of the poem needs context. I find it hard to create context in the short space that most line poetry requires. And the rhythms of prose poems are just more my style, my internal voice. In fact, I was thinking yesterday that my poetry reflects a kind of inner voice that needs time to complete. if that voice isn't taking time to reflect the thoughts clustering as they do, and there are times when the voice isn't talking, i just don't write.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I'm a messy writer. Copious notes, you could say. I never like my first draft. I look at my first drafts of anything and find them derivative, boring, not interesting to me. So, if a poem is boring, I abandon it for something else. But when something i need to say grips me i don't stop until I have a draft that expresses what I mean. But even then, I may not be happy with what I've got. For example, I'm writing poems right now about the war in Gaza (which is not a war). I don't know what to feel about the poems. I read them and know they are unfinished and possibly just not appropriate (who am I to write about this event?) And so the project has a 'body' but I don't think has shape. I have lots of these poems that are connected but ultimately, not ready for an audience. Basically, the project is a mess.

But my process is also messy because I don't know what I mean to say when i start to write. The draft comes out and it's not hanging well, and I push and pull at it to make it hang. And even after I've got it hanging, I realize it has no life. So how do I breathe life into it? So I fiddle until it feels like it's working. Or abandon it. I abandon things a lot and then come back to them. Or they return to me.

Starting a project is usually inspired by word associations. A poetic conceit. Disorder, for example, came into shape after being diagnosed Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD). I saw that the poems articulate what I experience living with BPD which is a trouble with borders, an obsession with order, and a tendency for chaos, or paranoia.

Projects just happen. Sometimes projects take a long time to take on the final shape, and sometimes they're just there. Then again, to be fair, when the project comes into shape as just there, it's usually after i've been stumbling around in the bushes for a long time. In fact, one project that came together just like that actually is littered with bits of content I'd been writing thirty years before. Literally those lines stuck with me for thirty years until they found a place to 'settle'. But even that project isn't finished or it's not something for an audience yet. Still working on it.

4 - Where does a poem or work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I combine pieces. I don't have the vision of a book until I can feel the pieces have a large meaning. I also find that I rarely am satisfied with one poem. I start a poem, a prose poem, and when the dust settles, another piece follows and after a while a third and fourth. So a single poem can have many pieces. The serial poem is my style. Or the long poem. There are several examples of these in Disorder and in Discipline N.V.. On the other hand, an essay may demand more essays. I wrote a group of essays on the topic of suicide, for example. I'd say that I had a few essays on suicide before I had a vision of the book.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I'm the sort of writer whose anxiety makes readings a nightmare. I mean I can do them now, when at one time, I could barely complete my reading without fainting. My stress level was so high and I was so 'on stage' in the experience that I was barely breathing. Now, after having taught for several years, i can breathe in front of people when on stage, but that's about as much as I can do. if I make a joke that's total victory. Because I can't do banter, because I'm so shy I rarely feel relaxed enough to give context for a given poem. That means I need to shape my readings around the script of my poem/prose delivery. I work hard on delivery. But I hate the experience of having to perform.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

See #7

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

When I was a kid making art, I wrote little plays and poems and I painted. I wrote and I created material objects out of clay and paper and fabric and wood. And then one day I knew I needed to choose one or the other art form and I chose writing. I chose writing because I wanted to express the truth. I'm not even sure what I meant by that at the time but today I see that the writer speaks the truth of their zeitgeist.

I see the writer as participating in addressing contemporary ethical concerns, or engaging in social justice. I see that happening in the writing community with writers speaking from their position as LGBTQ2S+, or BIPOC, or their disability. So I make my contribution as a white settler women living with a disability. What I worry about is that this specialization of our 'truths' may mean that we can't speak on topics not directly related to our position. I'm going to harp back to the issues raised by my writing about the war in Gaza. What right do I have to write about it? That leaves me speechless. But I am full of speech when it comes to what is happening in Gaza. But what is my ethical position to that event as a writer with all the privilege to be well fed, and not worry about where I'm living, but being neither Palestinian and nor Jewish? I'm not saying these things to apologize but to try and sort out why I am having trouble with writing about a contemporary crisis about which most of us have a position and about which I am compelled to write.

This dilemma I think is part of the role of the writer in culture: does the writer have a right because the writer writes? We all want to know what Zizek has to say about what's happening in Gaza, and he's got all the privilege possible. He's a writer and a thinker and that gives him the right. Does he have the right? And the answer seems to be, yes. So why do I think I don't have the right?

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

For the longest time, I wrote alone because no one got what I was doing. It meant that I was always struggling to figure out how to make my work stronger and better for publication on my own. I mean being rejected so much did a number on me and left me feeling completely inadequate. So I created my own voice, or form, I think. Or maybe I didn't. In any case, it has only been in the last 10 years of writing that I've had good experience with editors work with me in my writing. I'm not counting the experience of my MA which is years ago, because those editors weren't working with me for publication.

I don't know if working with an editor is essential, since I worked without for so long. But i would say that having a trusting relationship with an editor is essential. Building that trust, using my experience with Shane Neilson and Jim Johnstone as most recent examples, has been productive and so fulfilling. I also want to acknowledge the great trust I had working with John Barton and Jason Camlot.

I'd say that difficult is there if we consider trust being something that has to be be built. Building anything valuable is difficult. Writing poetry is, fundamentally, difficult. And that doesn't stop us from doing it.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Never give up. A 'no' in the publishing industry is a qualified 'no'. Losing in a grants competition is a qualified 'no'. Keep working at what you're doing and eventually an audience will form around you. I mean, when you ask yourself: should I give up? A voice in you will tell you: don't give up.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to short fiction to creative non-fiction)? What do you see as the appeal?

In one way I would say it's been quite easy since I write a hybrid form to begin with. Moving between poetry and non-fiction is enjoyable for me because I can test the limits of each genre. So while I can move between genres, I find that a project asks for a certain form, even if it started in the opposite genre.

For example, i was writing prose poems on suicide but then realized there was far far too much to say than a poem could handle. So I started writing essays, lyric essays, and the form stuck for this project now published as Stars Need Counting: Essays on Suicide. The Disorder project was a collection of poems that wanted to be defined, so I wrote a lyric essay to end the book. The lyric element of this project introduced a facet to the topic that the line poems could not have done which led me to realize that some projects want to be expressed in several forms.

So for me, going between genres is enjoyable and I advise everyone to do it. The other thing I'd say about moving between genres is that this movement can unstick writer's block. I discovered this way back during my MA when I was struggling so much with my fiction project. Poetry saved me. I'd say that is appealing, to save oneself from writer's block.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I write when the impulse grips me. I write something every day, if only a journal entry. But I don't write the 1000 a day that Stephen King advises. And maybe that is working against me. But then again, i don't write novels. But when I write long projects, sometimes everything I write is for that project and I can write (and revise) daily. It depends. Right now I'd say I'm between projects. So I'm not writing daily. And working means that I don't have the time to work on my creative work.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I read novels and poetry and some non-fiction. Right now I'm reading non-fiction by people living with BPD. I watch films (on Netflix usually). I'm watching Baby Reindeer, which is a bizarre British series about a man who creates chaos in his life. I always want to start painting again but every time I realize I need paints and canvas and all these objects to start painting, I sit back and imagine what i'd paint and that's almost as good as actually doing it. Inspiration also comes to me from the news (Al Jazeera, Ha'artez most recently). And my feelings. BPD are known for suffering emotional dysregulation. So, my feelings inspire me a lot.

13 - What was your last Hallowe'en costume?

Blondie with red lips. From the neck down, I'm dressed in puffy coat and jeans like anyone else in the neighbourhood giving out candies at the door.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Film is probably the biggest influence. Astronomy (astrology) and some versions of physics. And psychoanalysis big time.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Academia has been a big influence on my writing. I am a thinking writer. I am driven by thought more than emotion. This I'd say is a failing or a weakness in my work. I find it hard to express emotion which is ironic considering I have BPD (emotional dysregulation). Or maybe thoughts are my way of controlling emotion? So I'm inspired by writers such as Anne Carson who thinks as she writes.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Write that novel that's been simmering for a while. I have a vision that in my old age, when I have time to just ruminate, the novel will come, the thing that I've been trying to get down on paper for about thirty years. I can see where it'll be set (the middle east) and I can see what the issues are, but I can't see the protagonist yet. Until I have that protagonist, I can't start...

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

In grade 9, I decided I had to give up painting to be a writer. But I still love painting. I get excited looking at art and I have even started looking at the world in shapes which I can see translated to a canvas. I can see how a face could be painted: the planes, the shapes, the section of shadows. I can see bodies as shapes, and how a leg is articulated in angles and slopes. If I hadn't got stuck on the word, I would be a painter. Or a filmmaker. Or an astronomer.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

See #17

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Right now I'm reading a book of testimonies of people with Borderline Personality Disorder. I cry while reading each story. I hear the suffering, I recognize myself. I distinguish my experiences from theirs and wonder what those differences might mean. It's a simple book, but as an honest book, it has had a great impact on me.

So I watched Zone of Interest the other day. It was a striking film. I could appreciate the European understated quality of it. I also watched fascinated to see what Jonathan Glazer was trying to do. I didn't even have to hear his acceptance speech to see the parallels between the Holocaust and the conditions in the Gazan war.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I'm working on a project in dialogue with a fellow poet on the benefits and hazards of Dialectical Behaviour Therapy for people with disorders. The objective in the project is to be critical of the method from a disabilities perspective.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Wednesday, May 29, 2024

Luke Kennard, Notes on the Sonnets

‘Lo! in the orient when the gracious light’ (7)

Language, although it’s

not said so often, is actually brilliant. I mean just look at it. We took too

many pointers from depressed short story writers when really language is so

wonderful I can only celebrate it sub-lingually. I’ll rub my wings together or

something. I’m just going to come right out and say: that’s not a good reason

to have a son. It never even occurred to me. I only want to be temporary custodian

of a soul as strange as mine. But I know you’re trying to say something nice. Honestly

I like you and you’re beautiful. If you climb this hill it would make you very

old. Meet my replacement in the world; I think he’s upstairs playing on my phone.

I cannot accept the role of head of department because my contract stipulates I

avoid any role which could be described as “Oedipally significant”. In one room

a man stands by the dimmer switch, slowly turning it all the way up then all

the way down repeatedly. Not so much a fantasy as a mistake, and a barely plausible

one at that. Tell him to quit it.

Having picked this up recently at a bookstore in Chichester, England, I’m a bit late to British poet Luke Kennard’s Notes on the Sonnets (London UK: Penned in the Margins, 2021), a prose-poem suite that each play off a different one of William Shakespeare’s one hundred and fifty-four sonnets. As the back cover offers: “Luke Kennard recasts Shakespeare’s 154 sonnets as a series of anarchic prose poems set in the same joyless house party. A physicist explains dark matter in the kitchen. A crying man is consoled by a Sigmund Freud action figure. An out-of-hours doctor sells phials of dark red liquid from a briefcase. Someone takes out a guitar.” There is something quite fascinating about any text that is able to prompt such a variety of responses, allowing for a fluidity and mutability that even the genius of Shakespeare could never have imagined, and a list of further responses to these sonnets over the past few years alone would make an impressive (and essential reading) list: Vancouver Island poet and critic Sonnet L’Abbé wonderfully inventive Sonnet’s Shakespeare (Toronto ON: McClelland and Stewart, 2019) [see my review of such here], Manhattan-based poet Trevor Ketner’s homolinguistic translation The Wild Hunt Divinations: a grimoire (Middletown CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2023) [see my review of such here] and even St. Catharines, Ontario poet and critic Gregory Betts’ more recent visual epic, BardCode (UK: Penteract Press, 2024).

There

is a heft and an immense sense of play to this collection, structured nearly as

a collection of self-contained pieces that accumulate into something far more

complex, reminiscent my experiences reading through J. Robert Lennon’s short

story collection Pieces for the Left Hand (Graywolf Press, 2005) and Joy

Williams’ short story collection 99 Stories of God (Tin House Books,

2016) [see my notes on these two here]. The narrative arc of Notes on the

Sonnets might not fully exist, and yet, it does, even if only in the mind

of the reader, seeking out patterns across a wide array of notes, moments, seeming-randomness

and a party that seems endless, captured across more than two hundred pages of

Kennard’s deep-thinking prose. If James Joyce could write out a day, why not this

suite of prose poems around a party as well?

Tuesday, May 28, 2024

How many kilometres to London Towne?

“When a man is tired of London, he is tired of life; for there is in London all that life can afford.” Samuel Johnson

[see my report on the first part of our journeys here and the second part here]

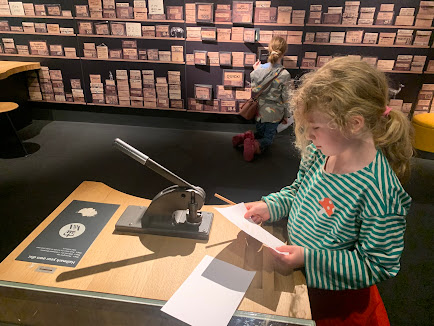

Thursday, May 16, 2024: Back in London, where the young ladies played a bit with their cousins before cousins headed out to school, and the four of us headed to the Victoria and Albert Museum, a space the children were enjoying well enough up to a point, but also barely tolerating. We took the tube, as Aoife offered coins to buskers in the station. Once at the museum, the children were already hungry, so we made for the cafeteria, adorned with an array of stained glass windows. The young ladies were not fully convinced. Rose wanted to go shopping. At least there was a space to press images into paper, as a kind of royal mark, which they young ladies enjoyed.

We moved through some of the metal-work and portraiture, but it was through the jewellery exhibit that their interest was, at least, sparked. I had hoped to get into the photography exhibit from Sir Elton and David's collection, but the young ladies were having none of that. I'm both hoping and presuming it lands at Ottawa at some point (although that could be a few years away, I know).

Rose, attempting to replicate a pose.

I think the longest we spent in the building at all was the gift shop, where I complimented one of the staff on the intricacies of her tattoo, and discovered that she was from Colorado.

After the museum, Christine had booked us a nearby 'dinosaur tea,' which doubled as lunch; wishing to introduce the young ladies to that most British of rituals (but dinosaur-themed). There were small cakes and treats shaped like dinosaurs and dinosaur eggs, and dry ice providing a bit of smoke from the plates. They were pleased.

The cafe sits in a basement corner of The Ampersand Hotel (it was very fancy). On the way to the washrooms was this artwork that I quite liked, "Assemblage" (2012) by Alex Petrescu, although I couldn't find any references for the artist online.

From there, we headed over to the Natural History Museum (although we had hoped to spend far more time in the Victoria and Albert), a space that held an array of constellations upon the wall. I'm always amused to utilize Christine's phone for constellations, the Star Chart app that allows one to see constellations in whichever direction you point the phone, including all the ones that we can't see from North America, on the other side of the earth, such as "Billy the Cowboy," or "Three Bears in a Trenchcoat."

It is interesting to compare some of these other natural history museums in other places, other countries, and be reminded how lucky one has it by being near Canada's Museum of Nature; the one in Chichester was okay, but small; this one is very impressive, offering an array of alternate information, given the different geographical focus [Rose and I visited similar in Washington D.C. in 2015, but she moved too quickly for me to get any useful photos of such]. And it would be impossible to not be blown away by the architecture and scale of the building.

And then back to Hammersmith, where the young ladies spent some good time with their after-school cousins, and I crashed a bit, preparing for the evening. I had been working a couple of weeks attempting a poet-gathering at the pub right by brother-in-law's place, The Queen's Head, but schedules didn't necessarily align with interest. I had booked a table (which was good, as the pub was rather busy), and waited for those who might show (while going further through Luke Kennard's sonnets, and a collection of interviews with American poet Peter Gizzi I'd brought along as well).

There were a half-dozen local poets unable to make it, with two poets (I only discovered after the fact) that got caught up in other things, but it was great to reconnect with London-based Canadian poet and filmmaker John Stiles (right) after some twenty years, and what was Vancouver poet Sean Cranbury (left) doing in Hammersmith? The last (and only) time I'd seen John Stiles was in 2006, when Stephen Brockwell and I were in London touring around, and I attempted another gathering of poets: a evening quartet at a pub that included myself and Brockwell with London-based Stiles and Kim Morrissey, a writer/poet originally from Saskatchewan [see my notes on such here]; As for Sean, apparently he was at a hotel only a couple of blocks away, his wife, the writer Carleigh Baker informing him, I think rob is close to where you are and inviting poets for drinks? So random. It was a very nice evening: both Sean and John discussed their admiration for Alberta band The Smalls, and Sean was deeply impressed to discover that John had done a documentary on the band. John stayed for an hour or two, but Sean and I closed the place (which at this location is still the 11pm bell, in case you were wondering).

Friday, May 17, 2024: We woke for further adventuring, aiming ourselves for one of those double-decker bus tour things of get-on, get-off, taking the tube near Buckingham Palace. It took a while for an accumulated grouping of us to actually land a bus, as the stop by where we landed was out of service, and nothing was properly marked (and the guy selling tickets didn't seem terribly interested in helping properly).

But we rolled around for a bit, listening to bits of historical patter and buildings and sites and such (Hyde Park, for example), until Christine had us jump off at Hamley's, a seven-floor toyshop that she herself had visited as a child on family trips. Oh, there was much excitement. A whole floor of just Lego! A wing dedicated to Peppa Pig. British-specific Playmobile figures available only at this particular store, this particular location.

One of the twentysomething staff complimented my sunglasses, and I told him that I had picked them up from Corner Brook, Newfoundland; he said he was uncultured, and didn't know where that was (my fault, honestly). It reminded of Sean Cranbury responding to a British cab driver who asked where he was from, and the driver asking if Vancouver was in Norway? I am Greb, the young employee said, I am from Lithuania. We ended up in a conversation about sunglasses, one longer than you might imagine, really. Rose said he was only trying to sell me something (which he was not; we were literally discussing sunglasses).

Well, we couldn't stay in the toystore forever (and yes, some items were purchased), so we made for the bus again, attempting to loop around to Tower Bridge and the Tower of London [remember that other time we went through there?], before an attempt for a boat back to Westminster. Sean Cranbury sent a text offering that there was some kind of small publisher's fair happening at the Tate (and I had been hoping to get back to the Tate, especially after missing the David Hockney stuff the last time around), but there simply wasn't the time in the day (had I only known prior!). Sean only found out because he was literally at the Tate watching them set up, but didn't wish to hang around for the extra two hours or so before the event would have been open for the public. It would have been much fun to run through a London book fair, mainly to be able to meet so many folk in person for the first time. And apparently our tour-bus went by the building (and rooftop) where the Beatles played their final live show? (I wasn't able to determine which rooftop)

The Tower of London: it was interesting to move through this space a second time, catching elements I hadn't seen prior, especially when one is following the moods and interests of young children. During our prior visit, I think we were focusing more on the overview, including around the Tower itself, and Anne Boleyn. I followed Rose through a thread of corridors and towers, watching her catch (three times, on a loop) a short video history around Edward I, "the hammer of the Scots," and attempting to explain to her exactly what that entailed. Some of us might not have been in North America but for some of those histories; decisions that I attempted to let her know directly impacted certain threads of her genealogy. She does seem to have an interest in British history, which is interesting to watch (we spent a year or two watching Time Team, as you know; and I think she's done at least one school project on British Royals, including Elizabeth I). The young ladies attended to the ravens (at a distance), and admired the grounds. We went to see the Crown Jewels, Christine grimacing at the imperfect placement of the letters in the signage for same (some shoddy workmanship, there, Tower of London sign-folk).

My question: why were the puppets in the gift shop SCREAMING?

From there, we caught one of the tour-boats on the Thames, wandering slowly across the water to the perpetual banter of the First Mate, who claimed not to be a tour guide, but there for our safety. He was pretty entertaining, but there was a part of me that wondered if they put him on the microphone to keep him out of trouble. He informed that many asked how to keep straight Tower Bridge from London Bridge, as people were always confusing the two. He suggested that Tower Bridge is the bridge with TWO TOWERS ON IT, and London Bridge was the bridge that said, in big letters upon the side, LONDON BRIDGE. I think that clears all that up, certainly. He also pointed out a spa at our eye level underneath one of those bridges where patrons might occasionally forget that tour boats go by, and we might see some nakedness. He had us all wave in that direction. At least one person sitting in the spa waved back.

I also pointed out, to Rose, the London Eye, something we'd seen more than a couple of times across Doctor Who episodes. And did you know there's an Egyptian Obelisk along the Thames? Cleopatra's Needle, although the way the First Mate spoke, it was three thousand years old, as though it had been there since then, but apparently it was moved by the Victorians, in that way Victorians had of picking up items from other places and attempting to absorb as their own (apparently there's also one in New York). Hm.

Given Sean Cranbury was still in town, we met up at the pub again, he and I. Once the children (who were playing with their cousins) were settled, Christine came along for a drink as well, which was nice (her energies, especially by mid/late afternoons, doesn't always allow for such). As well, before either of them landed, I ended up in a conversation with one of the staff, who looked barely twenty, discovering that this very British-sounding young lady had parents who are both Canadian? Apparently they'd moved here before she was born, one from Montreal and the other from Toronto. She says she has cousins in Dorval (hey, that's where our car is!), Pointe-Claire and Banff. You should go to Banff, I said. It's lovely.

Saturday, May 18, 2024: We had to be up enough to be at the airport for 6am, which was miserable (we spent much of the afternoon prior, post-touristing and pre-drinks, packing ourselves and the young ladies), with brother-in-law Mike good enough to drive us to the airport. Half-way there, a text message saying our flight delayed five hours, so we turned right around and I went back to sleep. On our second attempt, we made it, and, thanks to father-in-law, a bit of time in the Air Canada Lounge (the young ladies going through the ridiculous magazines Christine had let them purchase at the shop in the train station). Just like the flight to London, both children refused sleep, watching as many movies as they could (with at least one if not both doing a re-watch of Mean Girls), before Rose actually crashed for a third of the flight. Six hour flight, five hours delayed. And once landed, back to our car in the parking lot (safe, but the windows coated in dust) and the two-hour drive back to Ottawa, as both children crashed rather immediately. They only woke once I had opened the doors in our driveway, and informed them that I'd picked up take-out (a happy meal for Rose, a&w for Aoife), completely unaware that I'd dropped their mother in the Beechwood area for a work-friend potluck she'd been hoping to get to.

I think it took at least three or four days for our sleep to settle. But at least school-mornings were easier on everyone.