I cant hear you

the lilacs are in bloom

and the underworld

is slow I’m slowly

listening to girls

sing about the rabble in

syrenerna

they’re at my door pöbeln

the girls are in the lilacs

syrenerna

I can’t hear them

I have a telephone number

tattooed on my shoulder

and the lyrics

of the song on the radio

seems to be they’re at

the door pöbeln

they’re at the door

drömmen it’s not

a dream summer never ends

the currency has lost the

language

inside language treacherous

lilac

language syrener made for

girls

like me for me the lilacs

bloom

like little fingerprints

hundreds

of bloody little finger

prints I can’t hear

you I’m listening to the

radio my wife

is feeding me pomegranate

seeds

she’s feeding me with

bloody fingers

it’s summer it’s summer I

can’t

hear you det är sommar

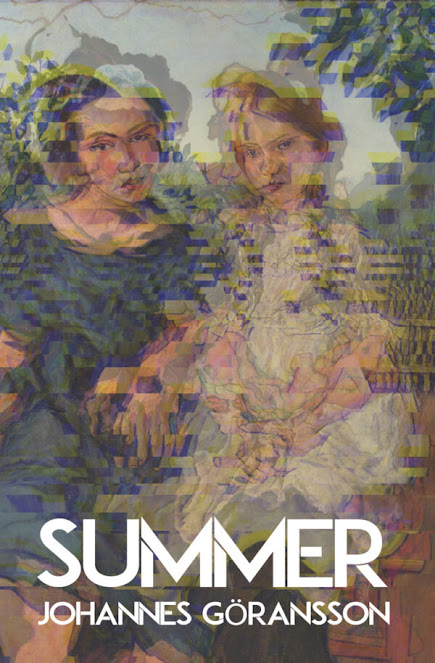

I’m really enjoying the rhythms and music of poet, editor and translator Johannes Göransson’s latest, SUMMER (Grafton VT: Tarpaulin Sky Press, 2022). Swedish born and raised, and living with his family in Notre Dame, Indiana, Göransson is the author of eight poetry titles, although this is only the second I’ve seen [see my review of his Poetry Against All: a diary (Tarpaulin Sky Press, 2020) here]. Between what I’ve seen of these two particular titles, Göransson works a threaded, thinking and continuous lyric, one akin to a journal or diary, allowing the ongoingness and repetitions to shape each larger book-length project. There is something intriguing about a lyric simultaneously held in the present moment, amid text and across a range of memory, moving from a gesture by his partner or one of their children, a thought on writing or film, and a series of recollections from childhood. The collage allows for a particular and tricky balance that appears to be done with ease, and allows for a lovely, continuous lyric flow. “How strange to wake up,” he writes, early on in the collection, “in this language / and be finished / with home be finished / with flowers och ett vackert hals / barnen babbler / like they are alive [.]” The music and rhythms of his lyrics are quite striking, one enhanced through the sprinkling of Swedish words and phrases, edging into the boundaries of his mother tongue. One is reminded of Canadian poets Erín Moure and Oana Avasilichioaei, for example, both of whom weave in other languages into and through their own work, or the work of Canadian expat Nathanaël; all of whom, as well, have done extensive work translating the work of other writers. On the whole, this assemblage and accumulation of poems provide a variety of threads across an internal monologue, one where images are able to fully ebb and flow, fade and form, ebb and flow. If his lyric is water, he writes the whole length of a river. “How can you think / I’m listening / I’m bicycling / which means cyclamen / cyclidium geranium / or the poison I’m marrying / to the summer [.]” He is writing memory, the present moment and family, as well as writing home, as his acknowledgements offer:

I began writing the book while staying in Fredrik Sjöberg’s apartment in Stockholm, looking at a painting of two girls on the wall: Anton Dich’s portrait of Lillian Arosenius and Hanna Gottowt. In my head I also had the title of Mats Söderlund’s first book, Det star en pöbel på min trap (There’s a rabble at my door). Also special thanks to Sten Barnekow for always finding me some place to stay in Lund, where I wrote a lot of these poems.

The poems curl, and loop, curl and loop; returning to repeated moments, repeated images. Curling up and around themselves, moving outward in concentric circles. “in the painting of ruins / I can hear summer,” he writes. Later on: “I can’t hear a thing/ tingling the thing I hear / is my wife doing that silver / thing to summer / until it’s over she is inte här / the summer is not over / here it’s still not over but she does / the end-voices in a landscape / painting with an ugly tree with / two girls from 1923 I can’t hear / her I know she is not here / you are here Lillian and Hanna you / will grow up to be history / I will grow up to be porcelain [.]” A bit further:

[…]

It's OK I’m impersonating

a kiss

of lilacs the dust covers

my photographs I only

ever write

about childhood

because that was before I

died

and now the devil has

brought me

back to summer in

Stockholm I’m starting to

make

sense of my body

which is becoming buried

in

pop music and now ooh-ooh

I have to write you a

letter

about my body as if it

were

split between foreign

words whispered by angels

and soldiers who march in

through the eye […]

There is such a grief and sense of loss that permeates the entirety of this collection, returning to summer and childhood, returning to children and poison, returning to a foundation of language and a portrait of two teenaged cousins painted a century prior. “To write a poem about violence,” he writes, as part of the second section, “while towers collapse is my scam / a summer scam I do it / while drinking milk of paradise / out of a rifle / but I have to get rid of it / the rifle before the party / starts the party of no / to enter undervärlden / you need a picture of yourself / with a noose [.]” Set in four numbered sections of accumulated, untitled lyrics—“For Lillian and Hanna,” “Flowers for the Riots,” “All the Garbage of the Sun” and “The World”—the first three hold to a structure of standalone poems, most of which each fit on a single page, set as single-stanzas of extended breath running down the page, until the fourth section, which is more fragmented, and extended: a layering of stanzas of one to six lines in a steady stream, all returning back to that poison, that painting, that room, circling into and across a poem about grief (far more grief, I would say, than violence, despite repeated references to an abstract and imprecisely described “violence”). And a counterpoint, perhaps, or sibling work to Joyelle McSweeney’s collection on their same, shared loss, her Toxicon and Arachne (New York NY: Nightboat Books, 2020). As Göransson writes in that fourth section:

I invented the meadow

in Giovanni’s room

because my daughter is

dead

and I needed it to mean

in Giovanni’s room everything

is garbage

nothing has value

and that is why I write a

poem

about violence

I write a violence

Given

his prior collection, Poetry Against All: a diary, was originally begun

while visiting his former childhood home in Sweden in 2013, a book constructed

out of entries excised from the manuscript that eventually became his book prior

to that, The Sugar Book (Tarpaulin Sky, 2015), one begins to see

elements of the larger pattern potentially at work: are these multiple

book-length projects begun during the same period of travel home, or are his collections

working into what the late Toronto poet bpNichol, or even the late Alberta poet Robert Kroetsch, worked throughout their writing lives, “a poem as long as a

life” extended through multiple, published collections? Are all of his

published books to-date, or at least these three, part of a single, ongoing

project?

No comments:

Post a Comment