When my legs slowly

paralyzed—heavy rain, wood, stone—I spent hours holding tight to the kitchen

table trying to lift each knee into the pressing air. An editor once asked in

an encouraging rejection letter why the manuscript had to be so depressing. (“Cataloguing

Pain as Marriage Counseling”)

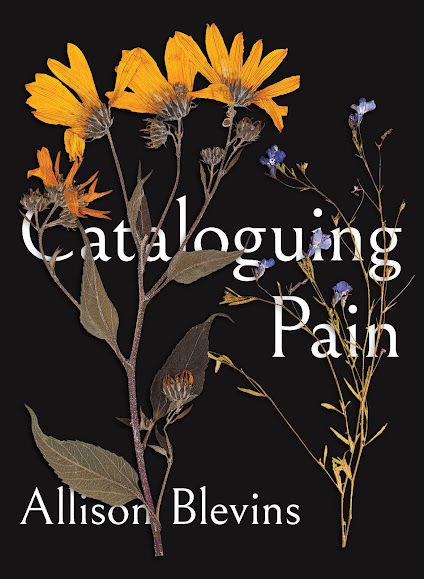

And so opens Minnesota-based Allison Blevins’ latest collection, Cataloguing Pain (Portland OR: YesYes Books, 2023), the first poem in an opening ten page sequence of one short prose stanza per page. Following Slowly/Suddenly (Vegetarian Alcoholic Press, 2021) and Handbook for the Newly Disabled, A Lyric Memoir (BlazeVOX, 2022), Cataloguing Pain holds echoes of Toronto poet Therese Estacion’s recent poetry debut, Phantompains (Toronto ON: Book*hug, 2021) [see my review of such here], both of which approach details to articulate living with and through relatively recent physical disabilities, from the experience of living with chronic pain to the physical needs and requirements of the body. As she writes as part of the sequence “Fall Risk”: “I want to ask you // to touch me, but it is Wednesday—shot day—and you’ve already loaded / the injector, swiped in outward concentric circles, pinched my stretched // and marked skin between your thumb and forefinger. / I want to fall less in love with you.”

“I track pleasures through color and sound.” she writes, as part of the sequence “A Catalogue of Repetitive Behaviors,” “When we wake the morning, our love is like an alarm blaring—pink-orange-morning-blues swirl and striate like cream in coffee. Love wakes the body like cologne lingers on the neck: this chair a proposal, this shirt a birthday surprise dinner.” There is such an intimacy to these poems, and an interesting way that the narration occasionally shifts from the main narrator to the voice of their spouse, offering the poems a broader portrait of how the changes affect them both, from pain into care, from parenting and pregnancy into attempting different ways to expand their small family. “My wife writes a letter to our son every year on his birthday.” she writes, as part of the sequence “A Catalogue of Repetitive Behaviors,” “In the days after this diagnosis, the rhythm of footfalls and the running washer across our house keep me awake and safe. I hear the clocks’ ticking in every room. I know the smell of her neck so well—lift me from the bed, help me with the socks.” Or, as the final poem in the six-part sequence “During the Days After My Official / MS Diagnosis” reads:

I can’t casually discuss what is coming for me. Our marriage won’t survive you explaining long term care insurance again. Today, in your group: a cousin in diapers, paralyzed child, incoherent texts from a sister in an assisted living facility, blind mother of six. Tonight, I will kiss our sleeping children in their beds. One last kiss before I turn off the living room light and walk across the house to our bedroom. I’ll brush my teeth. I’ll undress. I’ll climb into bed.

Blevins focuses on the form of the prose poem, including the prose sequence, to hold her accumulative insights; utilizing the form as needed, whether as blunt instrument, emotional force or as something more fine-tuned and precise, even liquid. “You ask how I feel.” she writes, further into the opening sequence, “Cataloguing Pain as Marriage Counseling,” “This is a trap. If I say my body hurts, not in my skin or fascia but in the spreading of pain along my nerves from my mother to my daughters. If I say inside me pain learns something new: how to web into the small and wet, loiter in the old rooms of diving and blue. You will reply, I’m sorry. I’d rather argue.” The poems in Cataloguing Pain are remarkably powerful through their subtlety, and deeply intimate across an array of notes, effects and difficulties catalogued alongside all that still remains possible, whether despite or through, pushing this as a collection that reads as fiercely optimistic, structurally dense and emotionally open. Everything about this book offers it as required reading.

No comments:

Post a Comment