ON WAKING

My lover says I have

called out

while asleep for beetroot

juice and saffron, declared

the colour of dove’s

blood is audible

and must

be written down. I don’t remember.

But know after waking I’ve

scavenged

old papers to find antique

recipes for ink, hungry

for a hallowed liquid to

write about Gorky. In dreams

he is tall and looks into

me.

Every morning his paint

rattles my thin grasp

on language.

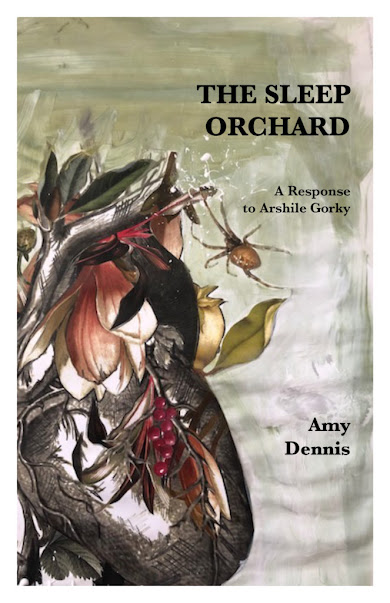

Having produced her chapbook THE COMPLEMENT AND ANTAGONIST OF BLACK (OR, THE DEFINITION OF ALL VISIBLE WAVELENGTHS) through above/ground press back in 2013, it is such a delight to see the full-length debut by Ontario poet Amy Dennis: The Sleep Orchard: A Response to Arshile Gorky (Toronto ON: Mansfield Press, 2022). The Sleep Orchard is presented as a poetic response to the work of the late Armenian-American Abstract Expressionist painter Arshile Gorky (1904 – 1948), who, as a contemporary of Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, was considered one of the most powerful American painters of the 20th century. “You loved me because I looked / like that period of Picasso,” she writes, as part of the sequence “MARNY GEORGE / AT 36 UNION SQUARE,” “when the walls were taken off / Pompeii. My pelvic cradle // a lava pond / filled with pottery / and ancient shards. I am almost dead / now. And you are ash in the meadow.” Dennis composes her book-length response via a sequence of self-contained narratives, each of which is set as a single step along a longer path; steps, or perhaps tarot cards: she turns over a card, each one offering a perspective that shifts, slightly, what might have come prior. And it is through this progression that she works to establish her portrait. As she writes to open the poem “STAGNATION, SWELL, / A SUDDEN FLESHING,” “The artist, / his hands, his mother’s absent / hands, painted over as clay blocks // because there’s no real way / of reaching.” There is something in the way Dennis works to not simply write through but into the work of Gorky, discovering, as well, the points where the artist and author begin to meet.

The poems of Dennis’ The Sleep Orchard move from examinations of specific artworks to certain biographical elements of an artist shaped through his escape from the Armenian genocide during the First World War as a child, to later suffering a variety of debilitating losses alongside his many accomplishments—a studio fire, the end of his marriage, cancer surgery and injuries garnered through an automobile accident—before he hung himself in a barn at the age of forty-four. As the poem “HIS WIFE, MOUGOUCH, AFTER / HER AFFAIR WITH MATTA” offers: “Moonstruck / raw, open for him // under the crystal liquids of a phosphor / chandelier—same light source, / years later, that the surrealists used, / blaming him for the suicide / of my husband, branding / his left breast with a hot iron, the word Sade / scorched over both // our breasts.” Her poems are emotionally dense, sharp and shaped but allow for a fluidity of lyric ebb and flow, working up to endings that less end than pause, perhaps, before one might either move into the next piece, or start over at the beginning. As the poem “GRIEF HAS NO WORDS, / ONLY A TRAILING OFF INTO THINGS / REMEMBERED INACCURATLY (MAKING / THE CALENDAR), 1947” begins: “This grey was once / made from the soot / of oil lamps. In its light, there were / voices.”

It is interesting that she refers to this collection as a “response” to Gorky, a designation that allows for critique, descriptive and biographical elements, but one that also isn’t constrained by those same details. One could mention a comparison to Edmonton-based Vancouver poet Catherine Owen’s own full-length debut, Somatic: The Life & Work of Egon Schiele (Toronto ON: Exile Editions, 1998), a collection of narrative lyrics suggested as biography but one, much as Dennis’, was shaped through the author’s own response to the life and the work of her chosen muse. And yet, in The Sleep Orchard, Dennis’ response is one that allows as much of herself to seep into the lyric as her subject. The poem “STILL LIFE WITH SKULL, 1927,” for example, is a poem that folds in the author’s separate experiences with childbirth and surviving a car accident with one of Gorky’s paintings. “The background of the painting a Delphic blue,” she writes, “tilting / at times into white // like my son’s umbilical cord before he was cut / from me. He was cut from me, our blood clamped. Last time // I felt pain like that was the car crash. I healed but my words / broke again as they made their way through my body.” It is as though, through exploring and responding to Gorky, Dennis is examining the very possibility of creating work through (despite and even beyond) her own shared layerings of physical and emotional trauma, whether parental loss, the ends of a marriage or injuries sustained in a car accident. Perhaps, through responding to Gorky’s losses and accomlishments, Dennis is able to see through his work to create her own. And for that, I am deeply grateful.

GORKY FINDS A PHOTOGRAPH

OF HIS MOTHER, FORGOTTEN

IN HIS FATHER SEDRAK’S

DRAWER

Did Sedrak feel pulled by

the portrait he left

in his drawer: her face—unframed,

scratching under a

scattering.

She starved. He slept

every night, clothed,

with a hatchet. Who knows

what his death meant for

Gorky, whether it swelled

the expanse of whale ribs

or Faust, if it echoed in him

as folklore. Or, like the

quick sting of sulfur

against phosphorus, the

pain was small—the first strike

of a match when one leans

in too close

to the flare.

No comments:

Post a Comment