I’ve been thinking diaspora

is & is not

the us of home & how &

where we’re enough&

how this nation demands

&

that nation extracts

&

that other nation seeks

but does not want us

to say hello ki leb

Acholi

one might ask quite

literally i tye

are you there

do you exist

are you

in response we might

say a tye

a tye ma ber

I’m here I exist I’m good I’m fine I exist

well

these poems are about that

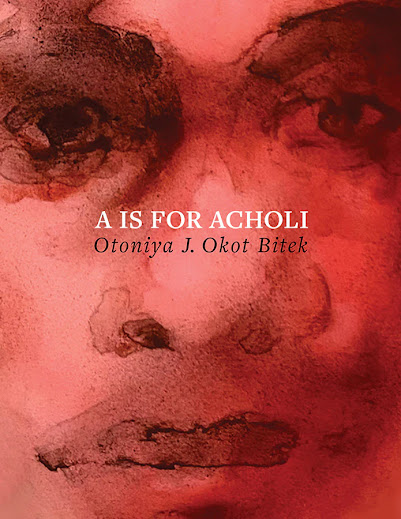

Award-winning Kingston, Ontario-based poet and critic Otoniya J. Okot Bitek’s second full-length collection, after 100 Days (Edmonton AB: University of Alberta Press, 2016) [see my review of such here] is A Is for Acholi (Hamilton ON: Wolsak & Wynn, 2022), a book-length poetic that works to articulate, dismantle and reconstruct an alphabet of being, seeking and belonging. “A is for Acholi Achol the Black one & the black one,” she writes, to open “An Ancholi alphabet,” “A is for the apple that was lobbed at us from a garden far away & exploded in our compound / A is for me [.]” A Is for Acholi is an expansive poetic through the archive, offering history, story and histiography, writing of diaspora and colonialism and dismantling racist depictions, all held together through such thoughtful and delicate construction. Bitek writes of homeland and of home; she writes of loss and of song and of standing firm on the present ground. “these days like loose threads like untied laces like / frayed edges like tenuous connections,” she writes, to open the single stanza (and punctuation-less) prose-block “An alphabet / for the unsettled,” “days like remembrances days like bits we can only access / if we’re to survive days that are untenable / palpable days pulsating through that prominent / vein on your temple days like memories you can’t / hold onto like last tuesday which means nothing at / all except that there was a tuesday last week [.]” Or, as the poem “Salt,” within the suite-section “If/once we were” offers:

this is land to salt to blood to red dust

land to map stories land to salt stories

Structured in two sections prefaced by a kind of lyric introduction (above), the opening section presents a twenty-six poem/page abecedarian “An Acholi alphabet,” before launching into a second section, the umbrella “A dictionary for un/settling,” which is itself broken down into six poem/poem-suites—“If/once we were,” “Excavating Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness,” “Settled/unsettled,” “There’s something about,” “The lock poems” and “Jacob’s breath.” The section “Excavating Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness,” for example, that opens with the poem “Three letters at a time,” is simply stunning, both visually and conceptually, and offers, as well, the footnote: “With gratitude to M. NourbeSe Philip for the teaching about the profane in the text & the work required for cleansing. To Jordan Abel for illustrating the poison through excavating the archive.” As this opening poem to the section begins: “Dark h n sh s c d be made out in the dis ce, fl ing in tinctly [.]” Her responses throughout this particular section are stunning, and delight in their deconstruction of Conrad’s novel, allowing for the physicality of the text itself to be torn down and, thusly, rebuilt in a form and manner both concrete and ephemeral. She makes the words and text characters he utilized purely hers, reordered and imagined into something other, else.

The

book also includes a “Postscriptum” at the end, which exists simultaneously

beyond and within the bounds of her book-length lyric, straddling that line

between poem and postscript, possibly as a conclusion to her expansive lyric

thesis. “& in / these days of this thing we might remember that we’re still

here we’re still / here we’re still here & our tongues will carry the rhythm

of how we came / through,” she writes, to end her two-page (and heavily

footnoted) “Postscriptum,” “all those past apocalypses & how we will learn

to draw maps again / & how history can & will be challenged with more

of our own stories in our / own languages because because because we now know a

world without empire [.]” Her notes-as-poems, or poems-as-notes, provide added

layers of consideration upon a sequence of already complex lines and links as

she writes history and lineage, linkages cultural and complicated.

No comments:

Post a Comment