BIRD

What is a bird? How much does it cost? How much does its cage cost? The going price for laboratory mice is twenty six dollars an animal. What is it for birds? They used to sell them around the river, dry wicker cages, dried ribs like parallel construction. They sold them before I was born. How much did one cost then? How much would it cost not to be silent? You do not speak for yourself. Not while doing science. Abandon the project. Go back. go into the cage. Write about what you know. Tell me how to lower my voice near enough to silence so that the whole world can be heard, even the windings inside of this body can be heard, and finally I will know what stepped onto the park grounds and make an about face, turns around to look.

It turns out we know

nothing about birds, neither the birds that have returned to the ponds, nor the

ponds themselves, artificial as slaughter, whose overgrowing weeds are pulled

out each night and burned. (Who does the burning? Where do they put the ashes?)

Late night, walking home by the re-growing, re-heightening reeds slender as the

knife tracks on a butcher’s board, I saw one bird hop branch to branch, like

all of its kind baring a fantastically large breast, a rust red quarrel with

air. I stopped. I looked.

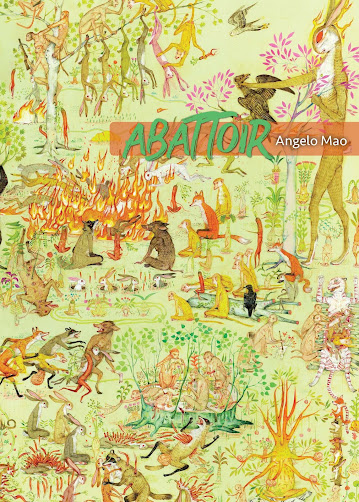

Winner of the 2019 Burnside Review Press Book Award, as selected by poet Darcie Dennigan, is California-born Massachusetts poet and research scientist Angelo Mao’s full-length debut, Abattoir (Portland OR: Burnside Review Press, 2021). Constructed as a suite of prose poems, lyric sentences, line-breaks and pauses, Mao’s is a music of exploration, speech, fragments and hesitations; a lyric that emerges from his parallel work in the sciences. “They have invented poems with algorithms.” He writes, as part of the untitled sequence that makes up the third section. “They can be done with objectivity.” Set in four numbered sections, the poems that make up Mao’s Abattoir are constructed through a lyric of inquiry, offering words weighed carefully against each other into observation, direct statement and narrative accumulation, theses that work themselves across the length and breath of the page, the lengths of the poems. “The first thing it does / Is do a full backflip,” he writes, to open the poem “Euthanasia,” “Does the acrobatic mouse / Which rapidly explores / The perimeter comes back / To where it started / To where it sensed / What makes its ribcage / Slope-shaped as when / Thumb touches fingertips [.]” This is a book of hypotheses, offering observations on beauty, banality and every corner of existence, as explored through the possibilities of the lyric. Or the first stanza of the two-page “Dissection” reads:

Bodice the color of rose.

Ligaments

of cream. Undone: parted.

Opening

and for a brief moment

hooking breath

to a forced, indrawn

stillness so as not

disturb whatever

hypothesis might arise,

nor disturb the forceped

hand that enters

with its set of

impersonal instruments

as formal as beauty.

No comments:

Post a Comment