Throughout Desgraciado, Dominguez writes one-way letters, whispering secrets to a dead man so we may overhear. When I first read this collection back in 2016, I immediately recalled Jack Spicer’s After Lorca, a book where Spicer invokes Federico García Lorca as a dead and unrequited lover, much like Dominguez invokes the Spanish colonizer Diego de Landa. Yet, unlike Spicer, Dominguez seems to be sustaining the relationship only in order to wound back. These entangled forms of struggle (correspondence, translation, caretaking, poison) unfold within relations of duress that have lasted centuries, almost turning these letters into vengeance by correspondence. They mirror the proximity of colonial violence in these involucramientos, and yet they do so in order that we may dream beyond the relationship between de Landa and the poet. Through these writings, the colonized tries to free themselves of the colonizer, but the correspondence reminds us that colonial structures play out in intimacy precisely because those scenes are repeating themselves elsewhere in both public and private spheres. By openly bringing genocide into the bedroom, and the bedroom into the colonizer’s history, Dominguez changes the game. (“FROM OUR SHARED DISGRACE: Foreword by Raquel Salas Rivera”)

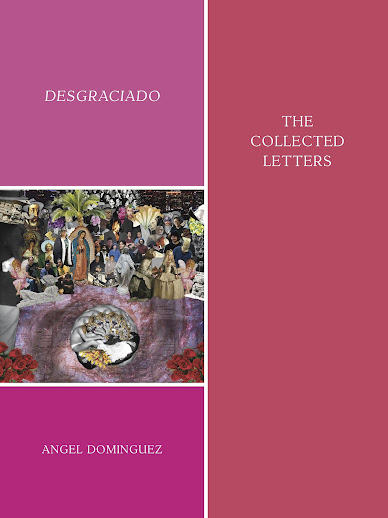

The third full-length title, following their novel Black Lavender Milk (New York NY: Nightboat Books, 2015) and “Phenomenological travelogue,” ROSESUNWATER (The Operating System, 2021), by Latinx poet Angel Dominguez is the newly-published Desgraciado: The Collected Letters (New York NY: Nightboat Books, 2022), an ambitious collection of epistolary poems that work to remake a colonial past and present, and a history that can’t help but impact upon everything that follows. “I don’t know what else to say.” Dominguez writes, early on in the collection. “I forgot why I was writing this / letter. I guess I just needed someone to talk to.” Less well known than the Spanish Governor, Hernán Cortés (perhaps, in part, due to Neil Young lyrics), Diego de Landa (1524-1579) was a Spanish Franciscan priest and bishop of Yucatán who is best known for his classic account of Mayan culture and language, most of which he was also responsible for almost completely destroying, through the mass burning of a number of Maya codices because he believed they were the work of the devil. Dominguez responds directly to the figure of de Landa, writing of a displacement that compounds across generations and decades, rolling across a language and culture lost through the direct actions of colonial powers (and de Landa, specifically). “The idea of this book burns / a hole through my abdomen; I can’t quite shake the quiet of my / ancestry. A lack left behind by the magic of globalism. Give up / a tongue to take another, and so now I write to you in English.” Dominguez writes of gaslighting and imposter syndrome, and the impossibility of fully being able to exist within their own culture, and writing their own personal loss of one language through the limitations of another. As they write, mid-way through the collection: “I let myself dive down to those Scorpio depths I’d been warned about: down to the bottom stone cold of a meticulous auto-immolation by way of language, and time. Does it matter? Diego, the sun is often fire, but sometimes soft. Clouds perpetrate a cold light that resembles the left cheek of the moon. I suppose there’s a lot that resembles distance. Language for instance.”

It is interesting to see this collection in relation to other works I’ve seen that respond to issues of empire, colonialism and generational trauma, including (but not limited to) recent titles such as Sonnet L’Abbé’s Sonnet’s Shakespeare (Toronto ON: McClelland and Stewart, 2019) [see my review of such here], Rick Barot’s The Galleons (Minneapolis MN: milkweed editions, 2020) [see my review of such here] and Jordan Abel’s NISHGA (Toronto ON: McClelland and Stewart, 2021) [see my review of such here]. There is such an intimacy and an insistence through these letters, writing through loss and a layering of trauma, from the historically-lost to those still to come. “See, I grew / up without this language. Without access to language.” Writing out a lush and insistent lyric, and an open-hearted and insistent engagement, with passionate resolve, Dominguez writes as a way to attempt to reach back through these layers, through the past to seek out these paths, these truths. “My darling,” Dominguez writes, mid-way through the collection, “did you really think your empire could ever end me?” The language here is stunning, writing a liquid prose alternating between propulsive and still, pushing against the possibility of a silence that can no longer contain itself. As the collection opens:

Diego—you dead man—I write to you.

It’s been centuries, I’m sure, since someone called out to you; now I do: Diego le Landa. The year is 2014 and the calendar’s been reset—your story buried beneath yr auto-de-fé burning our bodies down—we’ve no one to rescue that sound. But what am I saying? I speak English into robots and write to you in anything but Spanish—lengua Catalan—I wanted you to know, I’ve touched your soil and throughout Madrid and Barcelona I carved large red letters in churches and chapels, painted “MAYAN CONQUEST” on subways and buses, wrote “FUCK SPAIN” over every flag I could find. I started small fires in museums and stopped short of smashing mirrors and windows; I can’t erase you now—there’s too much to wipe out on data disks and clouds—fire couldn’t find you now—perhaps you’ll drown—I’ll pull you through dzonots on my gringo tongue—rinse your lungs clean with Xibalba water—what would you say to me then, and could your heart be pure?—I’d have to taste test the ash of your organs & fiddle with your bones to be certain I could trust you to go on dying, unacquitted by the light of time, I want your trial to continue; maybe I want to save you.

Love,

A

No comments:

Post a Comment