The Door’s Not Talking

When has the bookshelf

been so quiet?

It’s the sofa’s choice

whether to abstain.

Even from its

interrogation posture

the chair won’t budge.

The lamp is cornered.

Who will light the room?

Back to the wallpaper

and on the rug’s schedule

the mirror’s got nothing

to offer.

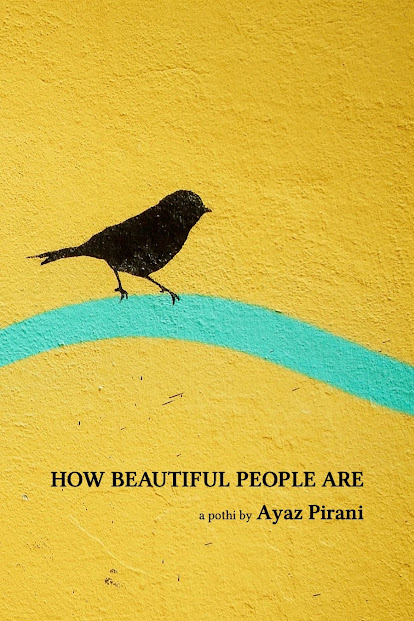

Ayaz Pirani’s third full-length poetry title, following Happy You Are Here (Washington DC: The Word Works, 2016) and Kabir’s Jacket Has a Thousand Pockets (Toronto ON: Mawenzi House, 2019) is How Beautiful People Are: a pothi (Guelph ON: Gordon Hill Press, 2022), a collection of lyric poems structured across four titled sections, three of which are predominantly built out of shorter poems—“BELOVED INFIDEL,” “DEATH TO AMERICA,” the sequence “(WHITE) CITY | KID (TROPIC” and “KABIR’S LONELINESS.” As to his subtitle, “a pothi,” SikhiWiki defies Pothi as “a popular Punjabi word derived from the Sanskrit – pustaka (book), from the root – pust (to bind) via the Pali – potlhaka and Prakrit – puttha. Besides Punjabi, the word pothi meaning a book is current in Maithili, Bhojpuri and Marathi languages as well. Among the Sikhs, however, pothi signifies a sacred book, especially one containing gurbani or scriptural texts and of a moderate size, generally larger than a gutka but smaller than the Adi Granth, although the word is used even for the latter in the index of the original recension prepared by Guru Arjan which is now preserved at Kartarpur, near Jalandhar.” The back cover offers that Pirani, through this new collection, “continues to write his people’s pothi: a trans-national, inter-generational poetry of post-colonial love and loss animated by the syncretizing figure of Kabir and drawn from the extraordinary diwan of ginan and granth literature.” From my own limited experience around poetries in languages beyond English, Pirani’s poems seem echoes of what I’ve seen of the English-language adaptation of the ghazal, bouncing from moment to moment underneath an umbrella of narrative, and not through the overt, linear thread. His is a lyric predominantly constructed through couplets, but one that allows for the mutability and durability of the lyric; an exploration that understands the simplicity and the complexity of the first-person narrative line, and the underlying song that the lyric itself requires.

There is something fascinating in the distances he manages through the use of the single word, “Long,” to open two different poems, allowing the single, opening word to remain solo in the opening space of the poem, before the piece continues on the following page. There is a pause, and a length he manages through this quite effectively, echoing a pause in the opening of the poem “Historical Disadvantage,” the second poem of the first section, to the poem “Saith the Missionary,” set as the second poem of the second section. As the first of this pair of echoing-poems continues: “have I lived among / white people. // Tell me I’m the lucky one / while I weep // at the Xerox / or curl up // with the other grains of sand. / I’d like to think // I’m living on the edge. / On a dog-eared page.”

“Not stitched to this place or any place.” he writes, to close the seven-part sequence that makes up the third section in the collection, “There’s no road to my village.” Pirani’s poems are constructed as meditations on origins, home, belonging, location and dislocation, and as a continuation of what might be seen as a disjointed path to where he has landed. “From a touch / you were born.” he writes, as part of the Creeleyesque “Origins,” “Grain of sand rubbed / grain of sand.” He composes home as a sequence of cultural and geographic spaces, each of which he carries, offering through the space of the lyric. He speaks of origins, and dislocation, writing out his lyric almost mythically, and as a kind of connective tissue across the whole of his life. It is through these poems of disconnection that the connections, thusly, reveal themselves. “At the party I’d like to be a person of interest,” he offers, to open the poem “POC RSVP,” “but will end up a person of colour. / Instead of agency I’ll get stuck with adjacency.” I’m particularly fond of the paired poems for his grandparents, the second of which, “Kilimanjaro,” begins by offering “My grandmother was a child of Empire.” He writes of Empire, colonialism and effects both tangible and intangible, and stretches a tether across great temporal and geographic distances, offering an intimacy to even the most distant shores of his subject matter. The short prose poem ends: “The whole story / takes place between my mother tongue and my grandmother’s / tongue. Even if all I have left is the faintest idea.” The poem for his grandfather, on the preceding page:

Ngorongoro

My grandfather was a man of other people’s words. He had the face of a dictionary. Born in Gujarat, he died after four continents and five languages. He’s been dead so long he’s come alive in my dreams. When you’re alone with your thoughts, you wish you had better thoughts. You wish you had somebody else’s thoughts. I’m glad to be on Earth but it hasn’t been a pleasure being myself. Too far from the source, a man who walked forward like his back was against the wall. Now that he’s gone I’ve fallen into the crater. There’s no good fortune in historical disadvantage. It’s so hard for one grain of sand to fall in love with another grain of sand.

No comments:

Post a Comment