October 12 or 15, the

twelfth

surely, certainly 2016

that I know,

your mother and I took

the train

uptown to see the Agnes

Martin

retrospective at the

Guggenheim,

and still a year and

change before your birth,

we hadn’t thought of

naming you Agnes

and wouldn’t until your

mother was

well into her pregnancy

with you.

Shakespeare’s wife Ann

was born

Agnes Hathaway, back when

people thought Agnes was

just

a version of Anna, which

is not,

like Agnes, from the

Greek but comes instead

from the Hebrew meaning “grace.”

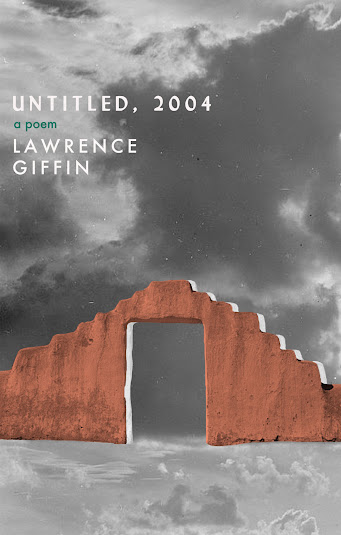

And so begins the latest poetry title by American poet and editor Lawrence Giffin, the extended poem Untitled, 2004 (New York/Kingston NY: After Hours Editions, 2020). Untitled, 2004 follows on the heels of his array of previous books and chapbooks, including Get the Fuck Back Into That Burning Plane (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2009), Sorites (Tea Party Republicans Press, 2011), Ex Tempore (Troll Thread, 2011), Christian Name (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2012), Just Kids (with Lauren Spohrer; Agnes Fox Press, 2012), Ad Pedem Litterae, 3 vols. (Troll Thread, 2012), Quod Vide (Troll Thread, 2014), Non Facit Saltus (Troll Thread, 2014), White Future (orworse, 2014) and Plato’s Closet (Roof Books, 2016).

“The trouble with beginnings is / they never take place quite at the / beginning.” he writes, close to the beginning of the collection (but not actually at the beginning). There is an ongoingness to this piece that is quite interesting. Giffin composes a long poem that moves through accumulation of section upon section, layering an epistolary meditation directed at his young daughter while folding in lengthy critiques and observations on the work and life of Saskatchewan-born American painter Agnes Martin (1912-2004), as well as a wealth of elements of history, theory and memoir. There is a sense of the epic throughout Giffin’s poem, as well as something deeply intimate and personal, sketched as a diary for the young Agnes, in a book titled after an artwork by her infamous and late namesake.

I wouldn’t say you were

named for

Martin, only that the

name Agnes

served to mark the promise

of those early days, when

everything that had gone

before

willy-nil toward an

indefinite future

was roughly abridged into

a prefatory note hastily

scribbled in anticipation

of what was sure to come

after.

Now we live in the relief

of waking from the

nightmare where

you are yet to be born,

which itself

was a nightmare,

medically induced,

expectant joy debrided

into merciful

deliverance.

Survival was the strait gate

through which you crammed

the contents of our world

compressed into an

age-old name.

“Boredom is the desire for desire, / desire at its purest and so also, / strangely, at its most empty.” Throughout Untitled, 2004, Giffin writes on boredom, error, desire, perception, reflection and observation, folding in other elements, artworks, conversations and thoughts along the way, from St. Augustine on craft, a wealth of observations on Agnes Martin and her work, to his thoughts on “an enormous outdoor maze / by Patrick Dougherty [.]” “I walk through museums, Agnes,” he writes, “like I walk through the mall: / purposeless loafing, letting the / fantasies on offer move in / and out of my consciousness / like curtains in an open window.” There is also a particular kind of pivot he discusses, about a third of the way through the poem, citing Agnes Martin’s habit of destroying the paintings of hers that she considered imperfect or flawed in some way, not wishing to allow an artwork with a “mistake” to exist; the pivot, of course, being she did this with all of the artworks she created that she considered imperfect, but for the singular piece Untitled, 2004, […] functioning thus / as the style’s own self- / consciousness, as the fulcrum / on which her entire career / pivots back on itself. It’s / as if her seven-year break from / painting and the accompanying / break in her style is referenced / in this splotch, which becomes / a sign of that difference between / the tension of the early works / and the harmony of the later ones.” Through this, I’m uncertain Giffin’s consideration of this, if he’s attuned to this particular artwork because of its perceived flaw and is thusly connecting his own pivot-point, composing a poem on attempting perfection and the further-beauty and further-possibility of imperfection through this particular epistolary-meditation.

Giffin writes on knowing and unknowing, and the benefits of being open to both, including the arena of falling full into what might otherwise be impossible. “Agnes, I know almost nothing,” he writes, towards the end, “and it has taken me nearly / forty years to learn how dumb / I’ve always been.” He writes of first encountering the woman who would become Agnes’ mother, and the first steps of their courtship, a story that includes wandering a gallery and seeing work by Agnes Martin. “The weekend / your mother and I met, she lost / her fingertip cutting kale, / and we spent the better part of / the evening in the ER, surrounded by / bloodied Chux, with curling wisps / of lunar caustic floating up / from the wounded nail bed. / Her pointer finger even now, / years later, remains disfigured / and, no longer round, / comes to a point instead.” There is such a wonderful openness to this book-length epistolary poem, one composed with the care and attention of a new parent and a deeply considered aesthetic, one that seeks to embrace a kind of change, however uncertain those changes might be.

No comments:

Post a Comment