Granny mama said that you wanted to name him Master.

Master never came outta my mouth. I always knew his name would be Sir. I named him Sir to honor my lineage, so that it would not be disrespected. The carrier of the name didn’t matter anybody could have been named Sir. You could have been Sir if you were first.

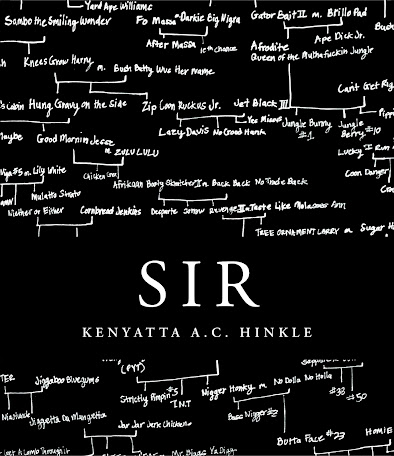

I’m fascinated by Berkeley, California performer, writer and artist Kenyatta A.C. Hinkle’s book-length poem SIR (Litmus Press, 2019; now available only through the author’s website). SIR is structured as a collage of image, text and archive to explore family, power relationships, segregation, racism and inter-generational trauma. Through a scrapbook of lyric prose, archival material, including family photographs, Hinkle writes on the histories and implications of being black in America, specifically her eldest brother, named “Sir” by their mother at birth (full name: Sir Antany Marquis Lavonne Hinkle), so anyone speaking to him would have to begin with respect. Hinkle explores the history of Louisville, Kentucky and her own brother’s name, including his own discomfort with it, referring to himself, instead, as “Anthony.” She writes: “His pants sag low as if he has a sack of shit in them. He wears a huge watch. His eyes squint when he is amused. He walks through life like anyone else. One step at a time. You would never know that his name is Sir and sometimes neither does he.” SIR exists as an expansive, loving and critical portrait of a name and a family, a time and a place; citing family photographs and a family shaped through and by an ongoing history. She writes archive and theory, trauma and naming, and how the name their mother gave her first born child both revolves and responds to elements of power and disparity:

They have been calling him by a name that is not his name and furthest from his name as his name can be. He hated Sir and still does. Even as I write this sentence he navigates the world with it under his skin. Tucked away in the cotton fibers of his birth certificate. Scared to make it emerge. Is it really fear I wonder? Is its use no longer needed? Fear comes through power. Power is the result of fear. What if he were named Power? Would he tell people his name was Strength, or even better same ole same ole same ole Anthony?

Opening as a map of his name, she evolves into an exploration of self and her larger family, including the lineage of her own given name. She explores her family’s history and genealogy. She writes of Louisville slave owner Captain Aaron Fontaine (1753-1823), from the park that bears his name across his former landscape, through her attempts at researching the names and details of the slaves he owned, and any potential descendants. She writes of the difficulty of a history she can’t fully research, and fully articulate. “I romanticize about a place that I cannot name. It is always on the top of my tongue but gets lost in the slippery saliva,” she writes, “and drifts back down my throat. Forming a knot, walking a fine line between choking, loving western shoes that hurt my feet and running around barefoot on the hot Kentucky cement.” Hinkle’s SIR is multi-faceted and expansive, with a lyric heft created through the deep dive she takes across her research, from the framing of her brother and her brother’s name into numerous acts and individuals that brought their mother to that point, and continue to affect their entire family. Hinkle’s SIR is framed very differently than, say, Charlottesville, Virginia poet and editor Kiki Petrosino’s White Blood: A Lyric of Virginia (Louisville KY: Sarabande Books, 2020) [see my review of such here], a book that covers a similar geography and history. SIR is far more intimate, more personal; writing her brother and his discomfort, and their mother’s discomfort. If White Blood is a book about how history impacts the present, SIR is a book about family, and how history impacted them and still does, directly and in an ongoing way; how their mother chose to respond, as an exploration of how that response ripped outward.

If we had a grandfather

and a great grandfather would they have named him Sir? Would he have been a

Jr.? Would Sir have been needed? If we all had arms and muscles to swing from,

to laugh and cry with us, to have their two cents put in and have it be the final

word would Sir need to be named Sir? If in our neighborhood the S.W.A.T. team

was not kicking down doors left and right because young men had taken over

whole apartment buildings for drug houses would Sir need to be named Sir? If we

didn’t care about black men at all in the world and wanted hate to eat them up,

with he need to be named Sir?

No comments:

Post a Comment