a brief note on the poetry of Fanny Howe

Through multiple collections of poetry and her most recent Gone (University of California Press, 2004) and Selected Poems (University of California Press, 2000), Fanny Howe’s poems seem to be all part of a long, ongoing line of stanzas from beginning to end, breaking down moment upon moment until they have accumulated into so much more than the sum of these individual parts. I like that at any point, any moment, I can open up any of her collections at random and simply read; simply listen. Does this make meaning/narrative meaningless, someone might ask. Meaning and narrative are made out of moments, and Howe knows all about moments.

LET IT SNOW

Let it snow unless it is in heaven

Let it know

what it is itself that waterstuff

as it covers the silver

winter dinner bell

Any ideas had in Canada on the long poem, the life-long poem, the poem as long as a life have long been writ of and spoke by the likes of bpNichol and Robert Kroetsch, among others (taken in part from Americans such as Jack Spicer, Robert Duncan, Charles Olson and William Carlos Williams), and the same consideration of the life-long poem can easily be said of the work of Fanny Howe. Lyrical and linked, her poems echo and re-echo off each other, and resonate in ways that don't require reading them (almost) in any particular order, dipping in to the poems in Gone where the fancy strikes. Built out of elliptical poems and prose sections, each fragment of her lifelong poem exists in its own moment, able to exist separately, but, as Jack Spicer once suggested, can no better live by themselves than we can.

Your heard is your tongue and the sweet jam that loves it

Your heart is your shoe, your place on the sod

Your heart is your baby cribbed in your ribs

Your heart is a tulip with a tulip-sign on it

Your heart is your brain

Your heart is a troubadour singing to wood

Your heart is a camel plodding along

Your heart is your ring that was reddish brown

Your heart is your sex and your mouth next to mine

Your heart is my heart that trails you in death

and guides me to the bird (a heart)

named Only-One-Song.

-- from “The Passion”

Saturday, December 31, 2005

Friday, December 30, 2005

bpNichol's Christmas cards

Since Ron Silliman recently mentioned Sheila Murphy's annual Christmas poem mailout, it seems only fair to mention the annual handout that bpNichol started, and his widow and daughter, Eleanor and Sarah Nichol, still continue since beep's death in 1988 at the age of 44. The tradition that bp started, through publishing new work, is continued by Ellie and Sarah through picking from bp's large stable of published work. This year, the poem fragment comes from his collection Zygal: a book of mysteries & translations (Toronto ON: Coach House Press,1985).

to encompass the world

to take it in

inside that outside

outside that in

to be real

one thing beside the other

Last year, Saskatoon's Grain magazine even did a special feature on bpNichol's Christmas mailouts (see the entry I made at the time on it here). It's a good thing I got it, too. The return address seems to be Calgary, and I was about to send her a bunch of things to the Toronto address (when did she move?).

Since Ron Silliman recently mentioned Sheila Murphy's annual Christmas poem mailout, it seems only fair to mention the annual handout that bpNichol started, and his widow and daughter, Eleanor and Sarah Nichol, still continue since beep's death in 1988 at the age of 44. The tradition that bp started, through publishing new work, is continued by Ellie and Sarah through picking from bp's large stable of published work. This year, the poem fragment comes from his collection Zygal: a book of mysteries & translations (Toronto ON: Coach House Press,1985).

to encompass the world

to take it in

inside that outside

outside that in

to be real

one thing beside the other

Last year, Saskatoon's Grain magazine even did a special feature on bpNichol's Christmas mailouts (see the entry I made at the time on it here). It's a good thing I got it, too. The return address seems to be Calgary, and I was about to send her a bunch of things to the Toronto address (when did she move?).

Wednesday, December 28, 2005

drinking red wine in glengarry county

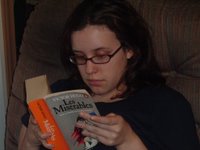

me + my lovely daughter Kate

It’s most of what I’ve been doing since coming out to my parents farm on December 23rd, just five miles west of Maxville, Ontario (home of the largest Highland Games in North America); that, and posting bits I wrote before I left Ottawa. Spending time with parents on the homestead, and my sister, her partner Corey and their daughter Emma (who just turned 2 years old; Kate and I take turns teaching her strange phrases to repeat very loudly) who live in the log house across the road (we’ve been on the same road since 1845). The poet Nicholas Lea is about two miles away on Norman Drive with his family, doing whatever it is they do.

I spent much of Christmas Eve reading a badly written book about Paul Chartier, who tried, unsuccessfully, to blow up Canada’s own Parliament in May 1966 (our own Guy Fawkes!'; see the related blog entry here). All he managed to do was accidentally kill himself, but only because he had no idea what he was doing. Reading the book, it’s actually rather frightening how close he came, failing only due to his own incompetence. The book, The Mad Bomber of Parliament (Nepean ON: Borealis Books, 2005) by James Fontana, seems to be well-researched enough, and Fontana was even on the front lines as a young lawyer (assistant Crown prosecutor in Ottawa), but really isn’t that well-written or compelling, despite the material, and presumes that the reader knows as many facts as the author does, such as mentioning the bus station on Albert Street (someone should tell him that it has long since moved; I have no recollection of it ever being there. Isn’t this something the author should be mentioning?).

Otherwise, I’ve been watching plenty of documentaries (The Real Da Vinci Code and Worst Jobs in History, both hosted by Tony Robinson, who seems to host a multitude of extremely interesting docs through BBC, and was Baldrick on Black Adder...), and episodes I missed of the past few months of Smallville (while waiting impatiently for the summer movie).

Yesterday, I went back to collect my daughter Kate (who turns 15 on January 4th; does that mean I'm an old guy?). We spent today wandering parts of Alexandria and Cornwall, doing nothing in particular (while listening to the mixed CD she made me for Christmas, with songs by Death Cab for Cutie, The Donnas, Air, The Bloodhound Gang, Coldplay and plenty of others; extremely cool). Our usual stops always include the Dairy Queen in Alexandria (I liked the building better, before the fire a few years ago; when on the farm without her, I spend most afternoons in there writing...) and the new/used bookstore on Main Street, where I usually leave handouts and pick up books on Glengarry history (if I can; most of them are bloody expensive). This time around I found The Scottish Pioneers of Upper Canada, 1784-1855: Glengarry and Beyond by (Toronto ON:Natural Heritage Books, 2005). Hopefully they'll be nice enough to send me a review copy if I ask all nice?

We return to Ottawa tomorrow, for whatever it is we do in the Capital. She’s been reading through the books I gave her, including Les Miserables (she requested it; she's actually a huge fan of musicals...) and The Astonishing X-Men: Volume Two, collecting the last six issues of the year long run of The Astonishing X-Men written by Josh Whedon (the guy who invented Buffy[I much preferred the movie], Angel and Firefly; I am very much hoping his run continues). In the kitchen, my father is currently working on his train (a lego-type huge model he got yesterday from Uncle Bob with nearly 1,000 pieces; he’s always been a big fan of puzzles, and other such things you have to figure out; far better than the 1980s, when he was the only one who played with my Rubic’s Cube by taking it apart and putting it back together in the right order, or the 1990s, when he would spend entire winters playing and solving the King’s Quest games, annually for the first three versions).

I was hoping to get a group photo of the whole bunch of us -- parents, sister, etc --but that doesn’t seem to have happened, again (couldn’t get one during the August long weekend either, during my sister’s third annual pig roast). At least something to show season (I'll just have to remember what they look like between now and March, when Kate and I come back here for March Break + my 36th birthday). Once I’m back at my desk, I’ll be producing smarter blog entries in no time. But one wonders, why?

Monday, December 26, 2005

George Bowering's Left Hook: A Sideways Look at Canadian Writing

Anyone who pays any attention to me at all knows that I'm a big fan of the work of Vancouver writer George Bowering [check out this new interview at P.F.S. Post], so it seems pretty obvious that I would be eventually talking about his most recent collection of criticism, Left Hook: A Sideways Look at Canadian Writing (Vancouver BC: Raincoast Books, 2005). Bowering has published a number of collections of criticism over the years, from the smaller publications How I Hear Howl (Montreal QC: Beaver Kosmos Folio, 1969), Al Purdy (Toronto ON: The Copp Clark Publishing Company, 1971), Robert Duncan: An Interview (with Robert Hogg) (Toronto ON: Coach House Press / Beaver Kosmos Folio, 1971), and Three Vancouver Writers: interviews by George Bowering (including Audrey Thomas, Daphne Marlatt and Frank Davey) (Toronto ON: Open Letter, Fourth Series, Number 3, Spring 1979) as well his larger collections of essays A Way With Words. (Ottawa ON: Oberon Press, 1982), The Mask In Place: Essays on Fiction in North America (Winnipeg MB: Turnstone Press, 1982), Craft Slices (Ottawa ON: Oberon Press, 1985), Errata (Red Deer AB: Red Deer College Press, 1988) and Imaginary Hand (Edmonton AB: NeWest Press, 1988).

Published right after he ended his two year stint as the first Parliamentary Poet Laureate of Canada, Bowering's Left Hook is over three hundred pages of essays and articles written over the years, including pieces on British Columbia, Al Purdy, Canadian postmodern fiction, the Véhicule Poets of Montreal, Robin Blaser, bpNichol, Mourning Dove, Ethel Wilson, Michael Ondaatje, appropriation of voice, and what it is to be Canadian, all with his usual style and wit. A number of these pieces even appeared as book introductions or afterwards, including to the Canadian fiction anthology he edited, And Other Stories (Talonbooks, 2001), as introduction to the anthology The Véhicule Poets Now (Winnipeg MB: The Muses' Company, 2004), and as afterward to Ethel Wilson's novel Swamp Angel (Toronto ON: New Canadian Library, McClelland & Stewart, 1990), as well as the piece "Diamond in the Rain," commissioned by the Neue Zürcher Zeitung that appeared online in English in John Tranter's Jacket magazine. In doing her own work on Bowering, Winnipeg poet Di Brandt recently suggested that George Bowering has done more work on other writers than just about anybody, and sometimes wrote the only (if not the only useful) critical work on particular authors. When looking at the volume of critical work he's done, you can even see it. One of the organizers of the Al Purdy symposium at the University of Ottawa that will be happening in spring 2006 suggested that Bowering's work on Purdy in that small booklet from 1971 is still the best critical work done on Purdy's work. When a writer such as Bowering does so many different things, and so many of them, it unfortunately becomes easier to overlook so much.

"Why do we visit graves?

Why would we travel to a place we have never been to before, and stand at the foot of a grave in which lie the remains of someone we have never seen in the flesh?

In the summer of 1992 I drove to Omak, Washington, to visit the grave of Mourning Dove, the first Native American woman ever to write a novel. At the tourist bureau they had never heard of her, but they told me that the graveyard I had mentioned was in Okanogan, the next town.

The graveyard, white and dry under the hot familiar sun, was deserted. I parked my car and got out and stood where I could see the whole place. Then I walked to the area that looked 1930s-ish. The first grave I looked at was hers.

She had bought this plot out of her minimal wages from hard orchard work, a grave in a white people's cemetery. In Jay Miller's introduction to her autobiography, I had read that the words on her marker were only "Mrs. Fred Galler" (xxvi). But now I saw that someone had cut a rectangle out of the old stone and put a new marker in its place. It depicts a white dove flying over an opened book upon which appear the words:

MOURNING DOVE

COLVILLE AUTHOR

1884-1936

There I was, a still living white male, standing, and eventually kneeling at the last narrow home of a great woman I had not heard of while I was being educated there in that Okanagan Valley. She died when I was seven months old. I did not read her books until I was the age that she had attained at her death. What did I think I was doing there? I was reading."

-- from "The Autobiographies of Mourning Dove"

Much more a collection of more general essays than most of his previous collections, as he writes more generally on postmodern fiction, Vancouver and British Columbia, as well as on particular works and particular authors he is interested in. One of the essays that might seem more relevant these days is his piece "Backyard Burgers: A Letter to the U.S.A. about Transborder Culture," originally composed as "a talk at Cleveland State University sometime in the 90s" that seems to be aimed as much at Canadians as Americans, that writes:

"My childhood was a battleground where the armies of the United States and Great Britain continued the conflict they had been conducting for a century and three-quarters. I lived in a valley where British was veterans grew tree fruits. So there were English accents all around me. I hated them. The reason I hated them was that they valley extended across the border, and so did radio waves. Most of the narratives I knew were from the U.S. From Donald Duck to Walt Whitman, they were my compatriots. The comic books I got, the novels I found in the drug store, the radio serials, the movies on Saturday afternoon, the sport magazines, the hit parade, the popsicle wrapper -- they were all made in the U.S.A., and they were not presented as anything but USAmerican stuff speaking to USAmericans.

Things have not changed that much. At the video store I go to they regularly list movies made by Canadians among the "foreign films." The movie theatre closest to my house bears a (relatively) permanent sign that declares its fare as "American and foreign movies." In the neighbourhood chain drug store that advertises itself as "Canadian-owned" you can get two hundred different paperback novels, but you can not find a Canadian novel among them unless Margaret Atwood has been recently reprinted. It took me years to persuade my daughter that the U.S. president is not legally our president. It took me longer to persuade her that we do not have a president.

I like to ask people from the U.S.: how would you like to go into a bookstore and find no USAmerican books? How would you like to go to a record store and find no USAmerican music, unless the musicians had become famous in another country? How would you like to buy a popsicle, and read the rules about saving up popsicle wrappers, and see in fine print at the bottom: "This offer not valid in the U.S."?" (p 16-7)

What I'm really looking forward to is Bowering's baseball memoir coming out sometime in 2006, although I'm not sure when (I'm pretty sure it's with Talonbooks), with sections that have already appeared in Open Letter and online at Toronto's Dooney's Café. Who knows baseball better than Bowering (although David McGimpsey's baseball piece in a recent issue of Matrix is pretty impressive; and then his book on it too?)? Don't talk to me of Field of Dreams, or Kinsella's Shoeless Joe…

Anyone who pays any attention to me at all knows that I'm a big fan of the work of Vancouver writer George Bowering [check out this new interview at P.F.S. Post], so it seems pretty obvious that I would be eventually talking about his most recent collection of criticism, Left Hook: A Sideways Look at Canadian Writing (Vancouver BC: Raincoast Books, 2005). Bowering has published a number of collections of criticism over the years, from the smaller publications How I Hear Howl (Montreal QC: Beaver Kosmos Folio, 1969), Al Purdy (Toronto ON: The Copp Clark Publishing Company, 1971), Robert Duncan: An Interview (with Robert Hogg) (Toronto ON: Coach House Press / Beaver Kosmos Folio, 1971), and Three Vancouver Writers: interviews by George Bowering (including Audrey Thomas, Daphne Marlatt and Frank Davey) (Toronto ON: Open Letter, Fourth Series, Number 3, Spring 1979) as well his larger collections of essays A Way With Words. (Ottawa ON: Oberon Press, 1982), The Mask In Place: Essays on Fiction in North America (Winnipeg MB: Turnstone Press, 1982), Craft Slices (Ottawa ON: Oberon Press, 1985), Errata (Red Deer AB: Red Deer College Press, 1988) and Imaginary Hand (Edmonton AB: NeWest Press, 1988).

Published right after he ended his two year stint as the first Parliamentary Poet Laureate of Canada, Bowering's Left Hook is over three hundred pages of essays and articles written over the years, including pieces on British Columbia, Al Purdy, Canadian postmodern fiction, the Véhicule Poets of Montreal, Robin Blaser, bpNichol, Mourning Dove, Ethel Wilson, Michael Ondaatje, appropriation of voice, and what it is to be Canadian, all with his usual style and wit. A number of these pieces even appeared as book introductions or afterwards, including to the Canadian fiction anthology he edited, And Other Stories (Talonbooks, 2001), as introduction to the anthology The Véhicule Poets Now (Winnipeg MB: The Muses' Company, 2004), and as afterward to Ethel Wilson's novel Swamp Angel (Toronto ON: New Canadian Library, McClelland & Stewart, 1990), as well as the piece "Diamond in the Rain," commissioned by the Neue Zürcher Zeitung that appeared online in English in John Tranter's Jacket magazine. In doing her own work on Bowering, Winnipeg poet Di Brandt recently suggested that George Bowering has done more work on other writers than just about anybody, and sometimes wrote the only (if not the only useful) critical work on particular authors. When looking at the volume of critical work he's done, you can even see it. One of the organizers of the Al Purdy symposium at the University of Ottawa that will be happening in spring 2006 suggested that Bowering's work on Purdy in that small booklet from 1971 is still the best critical work done on Purdy's work. When a writer such as Bowering does so many different things, and so many of them, it unfortunately becomes easier to overlook so much.

"Why do we visit graves?

Why would we travel to a place we have never been to before, and stand at the foot of a grave in which lie the remains of someone we have never seen in the flesh?

In the summer of 1992 I drove to Omak, Washington, to visit the grave of Mourning Dove, the first Native American woman ever to write a novel. At the tourist bureau they had never heard of her, but they told me that the graveyard I had mentioned was in Okanogan, the next town.

The graveyard, white and dry under the hot familiar sun, was deserted. I parked my car and got out and stood where I could see the whole place. Then I walked to the area that looked 1930s-ish. The first grave I looked at was hers.

She had bought this plot out of her minimal wages from hard orchard work, a grave in a white people's cemetery. In Jay Miller's introduction to her autobiography, I had read that the words on her marker were only "Mrs. Fred Galler" (xxvi). But now I saw that someone had cut a rectangle out of the old stone and put a new marker in its place. It depicts a white dove flying over an opened book upon which appear the words:

MOURNING DOVE

COLVILLE AUTHOR

1884-1936

There I was, a still living white male, standing, and eventually kneeling at the last narrow home of a great woman I had not heard of while I was being educated there in that Okanagan Valley. She died when I was seven months old. I did not read her books until I was the age that she had attained at her death. What did I think I was doing there? I was reading."

-- from "The Autobiographies of Mourning Dove"

Much more a collection of more general essays than most of his previous collections, as he writes more generally on postmodern fiction, Vancouver and British Columbia, as well as on particular works and particular authors he is interested in. One of the essays that might seem more relevant these days is his piece "Backyard Burgers: A Letter to the U.S.A. about Transborder Culture," originally composed as "a talk at Cleveland State University sometime in the 90s" that seems to be aimed as much at Canadians as Americans, that writes:

"My childhood was a battleground where the armies of the United States and Great Britain continued the conflict they had been conducting for a century and three-quarters. I lived in a valley where British was veterans grew tree fruits. So there were English accents all around me. I hated them. The reason I hated them was that they valley extended across the border, and so did radio waves. Most of the narratives I knew were from the U.S. From Donald Duck to Walt Whitman, they were my compatriots. The comic books I got, the novels I found in the drug store, the radio serials, the movies on Saturday afternoon, the sport magazines, the hit parade, the popsicle wrapper -- they were all made in the U.S.A., and they were not presented as anything but USAmerican stuff speaking to USAmericans.

Things have not changed that much. At the video store I go to they regularly list movies made by Canadians among the "foreign films." The movie theatre closest to my house bears a (relatively) permanent sign that declares its fare as "American and foreign movies." In the neighbourhood chain drug store that advertises itself as "Canadian-owned" you can get two hundred different paperback novels, but you can not find a Canadian novel among them unless Margaret Atwood has been recently reprinted. It took me years to persuade my daughter that the U.S. president is not legally our president. It took me longer to persuade her that we do not have a president.

I like to ask people from the U.S.: how would you like to go into a bookstore and find no USAmerican books? How would you like to go to a record store and find no USAmerican music, unless the musicians had become famous in another country? How would you like to buy a popsicle, and read the rules about saving up popsicle wrappers, and see in fine print at the bottom: "This offer not valid in the U.S."?" (p 16-7)

What I'm really looking forward to is Bowering's baseball memoir coming out sometime in 2006, although I'm not sure when (I'm pretty sure it's with Talonbooks), with sections that have already appeared in Open Letter and online at Toronto's Dooney's Café. Who knows baseball better than Bowering (although David McGimpsey's baseball piece in a recent issue of Matrix is pretty impressive; and then his book on it too?)? Don't talk to me of Field of Dreams, or Kinsella's Shoeless Joe…

Saturday, December 24, 2005

CURIO, GROTESQUES AND SATIRES FROM THE ELECTRONIC AGE, Elizabeth Bachinsky (Toronto ON: BookThug, 2005)

read one book

interested in speaking.

The door slammed. Carpet footfalls

echoed away.

'But they mocked the word

-- from "UNDRESSED AND SO MANY PLACES TO GO" (p 14)

What impressed me first about Elizabeth Bachinsky's first trade collection of poetry (after appearances in magazines here and there, and the anthology Pissing Ice: Canada's New Poets that appeared with BookThug early in 2005), is the way she knows how to make a poem look good, and play with the shape of how a poem exists, even throughout her own collection. Not all poems are built equally, so neither should they be built to look the same. Bachinsky's poetry works from the basis of convention and twists, as in this poem, opening up the collection:

ON THE CONVENTION OF NARRATIVE IN LITERATURE

Think of sailing the round earth to arrive at your point of departure.

You arrive, but the landscape has changed so much you don't

recognize it. A deck-hand calls to you from dry dock, but he

speaks a language you don't understand. So much has changed

in the time you have been gone, you sail right past the harbour.

In doing so, you have neither the sensation of a beginning nor the

sensation of an end. You have a different sense altogether. A middle

sense. The water moves beneath your ship, and there you sail. (p 9)

"This is a story of resistance." she writes in one of the first poems, and the collection is built on the simplicity and straightforwardness of that statement, later writing "This moment when you know you are should stretch on forever." (p 39). A resistance to what occurs outside and both inside her own spaces, Bachinsky's poems reach out and grab their own terms.

A cold song isn't wet feet, if Pip

Sired gold I'd mine your tit thus: sew my bed

Of reverend, a favor -- ever for rend.

Whole dulcet limbs hook youth.

Ape, attend your tired sex.

You, young, took wind, feverish winter desire, bent trial

You even find he's not even foam. A

Foolish dream she never knew to bake or hug. So, my

Aged teen, you down your youth.

-- from "REST HER VACANT TIMER: IF WE LET HER" (p 63)

read one book

interested in speaking.

The door slammed. Carpet footfalls

echoed away.

'But they mocked the word

-- from "UNDRESSED AND SO MANY PLACES TO GO" (p 14)

What impressed me first about Elizabeth Bachinsky's first trade collection of poetry (after appearances in magazines here and there, and the anthology Pissing Ice: Canada's New Poets that appeared with BookThug early in 2005), is the way she knows how to make a poem look good, and play with the shape of how a poem exists, even throughout her own collection. Not all poems are built equally, so neither should they be built to look the same. Bachinsky's poetry works from the basis of convention and twists, as in this poem, opening up the collection:

ON THE CONVENTION OF NARRATIVE IN LITERATURE

Think of sailing the round earth to arrive at your point of departure.

You arrive, but the landscape has changed so much you don't

recognize it. A deck-hand calls to you from dry dock, but he

speaks a language you don't understand. So much has changed

in the time you have been gone, you sail right past the harbour.

In doing so, you have neither the sensation of a beginning nor the

sensation of an end. You have a different sense altogether. A middle

sense. The water moves beneath your ship, and there you sail. (p 9)

"This is a story of resistance." she writes in one of the first poems, and the collection is built on the simplicity and straightforwardness of that statement, later writing "This moment when you know you are should stretch on forever." (p 39). A resistance to what occurs outside and both inside her own spaces, Bachinsky's poems reach out and grab their own terms.

A cold song isn't wet feet, if Pip

Sired gold I'd mine your tit thus: sew my bed

Of reverend, a favor -- ever for rend.

Whole dulcet limbs hook youth.

Ape, attend your tired sex.

You, young, took wind, feverish winter desire, bent trial

You even find he's not even foam. A

Foolish dream she never knew to bake or hug. So, my

Aged teen, you down your youth.

-- from "REST HER VACANT TIMER: IF WE LET HER" (p 63)

Friday, December 23, 2005

ubu web: Deanna Ferguson

sof

die

ta

tion

lim

ph

no

d I

are

-- from "Unwanted"

I recently discovered the /UBU EDITIONS series edited by New York poet Brian Kim Stefans (while looking up more material by Juliana Spahr, an American poet I've been reading lately), with titles published in pdf form in (so far) two seasons: winter 2003 and spring 2004. Publishing (and republishing) more challenging poetic texts that would be difficult to acquire otherwise, the series includes book length works by Caroline Bergvall, Robert Fitterman, Gustave Morin, Ron Silliman, Brian Kim Stefans, Kevin Davies, Juliana Spahr and Darren Wershler-Henry, among others, as well as two collections by Vancouver poet Deanna Ferguson, including Rough Bush and Other Poems, and a reissue of her earlier Tsunami collection, The Relative Minor. As Stefans says in his introduction to the first series:

"My hope, with the /ubu ("slash ubu") series, is to complement and augment relatively "traditional" methods of publication by usurping one of the most common functions of independent presses -- bringing vital new literature to the attention of a wider public -- while moving into an area that most small press publishers are not able to approach: reprinting important works from the past decades that are too commercially unviable to do as print books.

What made this idea seem interesting now, as opposed to eight or so years ago when internet publishing began its colorful but checkered history (prematurely vaunted by poets as the sequel to the "mimeo revolution") is the realization that people are willing to read long, complex works of literature from the internet provided they can print them out.

By formatting these books with professional typesetting tools and publishing them as Adobe Acrobat files, not only is the amount of paper needed to print out a book lessened because web page items like menu bars and graphics are absent, but the letter-size (8.5 x 11) page is transformed into a visually pleasing "book" page, its seductive gutters, leading and tracking making Cinderellas out of the plain-Jane ream of photocopy paper.

Publishers of innovative poetries on the web have always had trouble formatting works in html (which, among other limitations, does not have tag for a tab), but the ubiquitous Adobe Acrobat format is perfect for giving the designer all the features of advanced typesetting and graphic techniques that are stable and consistent across several computer platforms. A colour printer lets you fully enjoy the cover pages of these files, most of them original designs by Goldsmith and including one of the artworks from the ubu archives." (Stefans)

It's interesting that Ferguson's work moves from potentially having such a localized audience to a much wider one, with her part in the /ubu editions project (will there be a third run, I wonder, or a fourth?). Part of the Kootenay School of Writing collective in Vancouver during the time of Lisa Robertson, Dorothy Trujillo Lusk, Judy Radul, Jeff Derksen, Colin Smith, Nancy Shaw and others (see Writing Class: The Kootenay School of Writing Anthology), Deanna Ferguson's The Relative Minor was originally published by Tsunami Editions in 1993 (publisher also of texts by a number of the Kootenay collective. Kevin Davies' Pause Button, also reprinted here, was originally published by Tsunami in 1992; rumours have the press perhaps restarting in 2006?). An editor of Vancouver's late Tsunami Editions, as well as Vancouver's tabloid of arts writing from the 1990s, BOO Magazine, Ferguson's publications also include Link Fantasy, Democratique and The Goth Poem (Cleave), ddilemma (Hole Books), Rough Bush (Meow Press) and Small Holdings (Tsunami). As editors Andrew Klobucar and Michael Barnholden write of Ferguson in their introduction to Writing Class:

"Linguistic relations reveal further institutional ties in the work of Deanna Ferguson -- specifically the institution of patriarchy. Unlike Derksen's paratactic socio-economic commentary, Ferguson's lines at first suggest a more continuous narrative:

In using the telephone, she says, I really gave so-and-so

a good reaming, reprimand city,

Soon enough, circularities of story, intimacies shared.

Bullshit made apparent, but

What is constructed in this world

Has at least a shelf-life.

If there is contradiction in this work, it emerges at the level of syntax first. Ferguson does not clarify whether the adverbial clause "in using the telephone" modifies "she says" or "I really gave." In other words, is the subject using the telephone to give the other un-named conversant "a good reaming" or merely to tell she has done so? The logic of the narrative supports the latter meaning, for how could one make specific use of a telephone to reprimand a person, save as a device of communication; yet the syntax of the line suggests that in the actual use of the instrument, the reprimand was given. Similarly, the jargon "reprimand city" plays with two meanings, making a pun of her terminology. Even after closely considering the different sections of Ferguson's long poem "Wanke Cascade," from which the above is taken, the reader inevitably realizes that s/he is no nearer to a sense of "shared" narrative than when s/he began. The point at which the description or representation of the supposed event actually begins is not clear here. Ferguson displays two fictions simultaneously, or rather two levels of a linked fiction: "circularities of story, intimacies shared. / Bullshit made apparent, but…" Once again, the medium of communication appears to disrupt more than it transmits.

What in the romantic poetry of social anger or in a "work poem" might appear as a literal complaint cannot overcome its discursive origins, and so retreats back below the linguistic surface. Only "fabrication remains intact"; and this, Ferguson implies, remains the real target of her critique. The poet, and a female poet especially, cannot simply escape her social role or create a new one; her language works against it. But the ideological forces affecting her diction do not necessarily mean that she is completely powerless. It is no small feat to recognize and acknowledge the condition of one's exclusion. Exclusion carries with it its own shades of autonomy and possible freedoms. She concludes:

until all events speak for themselves

until representations know what it feels like

until positioning in the order is located

until orders of knowing suss up

until strata is axed as metaphor

until economic isn't always the organizer

fear, baby

Such are the demands Ferguson makes, not only on her social condition, but on language itself. To revolt against the political economy of liberal capitalism is to abandon all of its cultural institutions, including those guiding communication and representation. Once again, as she suggests, exclusion from mainstream culture invokes its own terms of agency and capability ("fear, baby"). Ferguson is in charge of her language to the extent that she doesn't have to communicate, if she doesn't want to communicate. Perhaps the most cogent example of this form of cultural defiance is her refusal to participate in this anthology. It is difficult to assemble works from so many disparate writers, despite their similar origins and collective engagements, without risking reductive categorizations of a poetry that, by its nature, remains highly dependent upon context for much of its import and innovation. Ferguson is right to be wary of being included in such a project, and she wastes little time in demonstrating her obvious sense of exclusion even here." (p 40-42)

In her collection Rough Bush and Other Poems, Ferguson gives us fifteen poems in under ninety pages, moving from expansive to tight lines, and blocks of prose, wide movements across the page, to thin strips of words. There have been discussions lately on a list-serve or two about if poetry is supposed to be uncomfortable, and I think it should be. And "uncomfortable" can end up meaning a whole swath of things, whether through content or form or any mixture of whatever else. Deanna Ferguson's poems could be considered "uncomfortable" only in the fact that they help challenge any notion of what a poem is "supposed to be," something that should almost always be challenged, and re-thought. Ferguson's poems move through areas of thinking and language that help keep an active blur, and a shift to what a poem is, or can be. For any of us who write, or read, I think it's a constant struggle to keep an open mind to new possibilities of form, and not become too comfortable in any one stance or area, and any of the collections published in this series have certainly achieved great strides in important and interesting directions.

We are welcomed by a special discordance.

In shape of an elder bushes morning.

He was forty-two and I seventeen.

Gone hum-speak-griddle to our boiling roles.

Darned compendium. Too close to a

hint of relative and plank-walled with respect

to the mouth. His nose hooked over my

untaxable cache. Pine hotel. Laid directly

on account of country. Straight through it.

Forty borders in a curious

line behind us. Woody with joints.

-- "Rough Bush," Rough Bush and Other Poems

sof

die

ta

tion

lim

ph

no

d I

are

-- from "Unwanted"

I recently discovered the /UBU EDITIONS series edited by New York poet Brian Kim Stefans (while looking up more material by Juliana Spahr, an American poet I've been reading lately), with titles published in pdf form in (so far) two seasons: winter 2003 and spring 2004. Publishing (and republishing) more challenging poetic texts that would be difficult to acquire otherwise, the series includes book length works by Caroline Bergvall, Robert Fitterman, Gustave Morin, Ron Silliman, Brian Kim Stefans, Kevin Davies, Juliana Spahr and Darren Wershler-Henry, among others, as well as two collections by Vancouver poet Deanna Ferguson, including Rough Bush and Other Poems, and a reissue of her earlier Tsunami collection, The Relative Minor. As Stefans says in his introduction to the first series:

"My hope, with the /ubu ("slash ubu") series, is to complement and augment relatively "traditional" methods of publication by usurping one of the most common functions of independent presses -- bringing vital new literature to the attention of a wider public -- while moving into an area that most small press publishers are not able to approach: reprinting important works from the past decades that are too commercially unviable to do as print books.

What made this idea seem interesting now, as opposed to eight or so years ago when internet publishing began its colorful but checkered history (prematurely vaunted by poets as the sequel to the "mimeo revolution") is the realization that people are willing to read long, complex works of literature from the internet provided they can print them out.

By formatting these books with professional typesetting tools and publishing them as Adobe Acrobat files, not only is the amount of paper needed to print out a book lessened because web page items like menu bars and graphics are absent, but the letter-size (8.5 x 11) page is transformed into a visually pleasing "book" page, its seductive gutters, leading and tracking making Cinderellas out of the plain-Jane ream of photocopy paper.

Publishers of innovative poetries on the web have always had trouble formatting works in html (which, among other limitations, does not have tag for a tab), but the ubiquitous Adobe Acrobat format is perfect for giving the designer all the features of advanced typesetting and graphic techniques that are stable and consistent across several computer platforms. A colour printer lets you fully enjoy the cover pages of these files, most of them original designs by Goldsmith and including one of the artworks from the ubu archives." (Stefans)

It's interesting that Ferguson's work moves from potentially having such a localized audience to a much wider one, with her part in the /ubu editions project (will there be a third run, I wonder, or a fourth?). Part of the Kootenay School of Writing collective in Vancouver during the time of Lisa Robertson, Dorothy Trujillo Lusk, Judy Radul, Jeff Derksen, Colin Smith, Nancy Shaw and others (see Writing Class: The Kootenay School of Writing Anthology), Deanna Ferguson's The Relative Minor was originally published by Tsunami Editions in 1993 (publisher also of texts by a number of the Kootenay collective. Kevin Davies' Pause Button, also reprinted here, was originally published by Tsunami in 1992; rumours have the press perhaps restarting in 2006?). An editor of Vancouver's late Tsunami Editions, as well as Vancouver's tabloid of arts writing from the 1990s, BOO Magazine, Ferguson's publications also include Link Fantasy, Democratique and The Goth Poem (Cleave), ddilemma (Hole Books), Rough Bush (Meow Press) and Small Holdings (Tsunami). As editors Andrew Klobucar and Michael Barnholden write of Ferguson in their introduction to Writing Class:

"Linguistic relations reveal further institutional ties in the work of Deanna Ferguson -- specifically the institution of patriarchy. Unlike Derksen's paratactic socio-economic commentary, Ferguson's lines at first suggest a more continuous narrative:

In using the telephone, she says, I really gave so-and-so

a good reaming, reprimand city,

Soon enough, circularities of story, intimacies shared.

Bullshit made apparent, but

What is constructed in this world

Has at least a shelf-life.

If there is contradiction in this work, it emerges at the level of syntax first. Ferguson does not clarify whether the adverbial clause "in using the telephone" modifies "she says" or "I really gave." In other words, is the subject using the telephone to give the other un-named conversant "a good reaming" or merely to tell she has done so? The logic of the narrative supports the latter meaning, for how could one make specific use of a telephone to reprimand a person, save as a device of communication; yet the syntax of the line suggests that in the actual use of the instrument, the reprimand was given. Similarly, the jargon "reprimand city" plays with two meanings, making a pun of her terminology. Even after closely considering the different sections of Ferguson's long poem "Wanke Cascade," from which the above is taken, the reader inevitably realizes that s/he is no nearer to a sense of "shared" narrative than when s/he began. The point at which the description or representation of the supposed event actually begins is not clear here. Ferguson displays two fictions simultaneously, or rather two levels of a linked fiction: "circularities of story, intimacies shared. / Bullshit made apparent, but…" Once again, the medium of communication appears to disrupt more than it transmits.

What in the romantic poetry of social anger or in a "work poem" might appear as a literal complaint cannot overcome its discursive origins, and so retreats back below the linguistic surface. Only "fabrication remains intact"; and this, Ferguson implies, remains the real target of her critique. The poet, and a female poet especially, cannot simply escape her social role or create a new one; her language works against it. But the ideological forces affecting her diction do not necessarily mean that she is completely powerless. It is no small feat to recognize and acknowledge the condition of one's exclusion. Exclusion carries with it its own shades of autonomy and possible freedoms. She concludes:

until all events speak for themselves

until representations know what it feels like

until positioning in the order is located

until orders of knowing suss up

until strata is axed as metaphor

until economic isn't always the organizer

fear, baby

Such are the demands Ferguson makes, not only on her social condition, but on language itself. To revolt against the political economy of liberal capitalism is to abandon all of its cultural institutions, including those guiding communication and representation. Once again, as she suggests, exclusion from mainstream culture invokes its own terms of agency and capability ("fear, baby"). Ferguson is in charge of her language to the extent that she doesn't have to communicate, if she doesn't want to communicate. Perhaps the most cogent example of this form of cultural defiance is her refusal to participate in this anthology. It is difficult to assemble works from so many disparate writers, despite their similar origins and collective engagements, without risking reductive categorizations of a poetry that, by its nature, remains highly dependent upon context for much of its import and innovation. Ferguson is right to be wary of being included in such a project, and she wastes little time in demonstrating her obvious sense of exclusion even here." (p 40-42)

In her collection Rough Bush and Other Poems, Ferguson gives us fifteen poems in under ninety pages, moving from expansive to tight lines, and blocks of prose, wide movements across the page, to thin strips of words. There have been discussions lately on a list-serve or two about if poetry is supposed to be uncomfortable, and I think it should be. And "uncomfortable" can end up meaning a whole swath of things, whether through content or form or any mixture of whatever else. Deanna Ferguson's poems could be considered "uncomfortable" only in the fact that they help challenge any notion of what a poem is "supposed to be," something that should almost always be challenged, and re-thought. Ferguson's poems move through areas of thinking and language that help keep an active blur, and a shift to what a poem is, or can be. For any of us who write, or read, I think it's a constant struggle to keep an open mind to new possibilities of form, and not become too comfortable in any one stance or area, and any of the collections published in this series have certainly achieved great strides in important and interesting directions.

We are welcomed by a special discordance.

In shape of an elder bushes morning.

He was forty-two and I seventeen.

Gone hum-speak-griddle to our boiling roles.

Darned compendium. Too close to a

hint of relative and plank-walled with respect

to the mouth. His nose hooked over my

untaxable cache. Pine hotel. Laid directly

on account of country. Straight through it.

Forty borders in a curious

line behind us. Woody with joints.

-- "Rough Bush," Rough Bush and Other Poems

Thursday, December 22, 2005

Juliana Spahr: this connection of everyone with lungs

New from poet and critic Juliana Spahr is the collection this connection of everyone with lungs (University of California Press, 2005), a highly personal and political collection of two long poems written in response to world events. The author of a number of works available on-line as PDF, including Gentle Now, Don't Add to Heartache, 2199 Kalia Road and Unnamed Dragonfly Species, her print works include Fuck You-Aloha-I Love You , Nuclear and Response (originally published by Sun & Moon in 1996, now available as PDF at Brian Kim Stefans' /ubu editions), which was also the winner of the National Poetry Series Award. Co-editor, with Jena Osman, of the international arts journal Chain, she recently moved from Hawai'i to Oakland, California. Built of two highly charged pieces that seem self-explanatory, the collection begins with "Poem Written after September 11, 2001" and continues with "Poem Written from November 30, 2002, to March 27, 2003."

But outside of this shape is space.

There is space between the hands.

There is space between the hands and space around the hands.

There is space around the hands and space in the room.

There is space in the room that surrounds the shapes of everyone's

hands and body and feet and cells and the beating contained

within.

There is space, an uneven space, made by this pattern of bodies.

This space goes in and out of everyone's bellies.

Everyone with lungs breathes the space in and out as everyone

with lungs breathes the space between the hands in and out

as everyone with lungs breathes the space between the hands and

the space around the hands in and out

-- "Poem Written after September 11, 2001"

There is something even eerie about getting my copy in the mail on November 30, 2005, on the anniversary of the beginning of the book's second poem, that starts with this small note:

Note …

After September 11, I kept thinking that the United States wouldn't

invade Afghanistan. I was so wrong about that.

So on November 30, 2002, when I realized that it was most likely that

the United States would invade Iraq again, I began to sort through the

news in the hope of understanding how this would happen. I thought

that by watching the news more seriously I could be a little less naïve.

But I gained no sophisticated understanding as I wrote these poems.

September 11 shifted my thinking in this way. The constant attention

to difference that so defines the politics of Hawai'i, the disconnection

that Hawai'i claims at moments with the continental United States,

felt suddenly unhelpful. I felt I had to think about what I was

connected with, and what I was complicit with, as I lived off the fat of

the military-industrial complex on a small island. I had to think about

my intimacy with things I would rather not be intimate with even

as (because?) I was very far away from all those things geographically.

This feeling made lyric--with its attention to connection, with

its dwelling on the beloved and on the afar--suddenly somewhat

poignant, somewhat apt, even somewhat more useful than I usually

find it.

Political writing is difficult, and there is something deeply personal and abstract in the way Spahr writes her explorations of the world. I've heard poetry described both as an exploration of language and a process in which to try to understand the world, and Spahr's this connection of everyone with lungs certainly works to explore those connections. There are strange things going on in the world, and these two poems ache in their response to but a few of these events. They ache and they explore and they struggle to understand, opening questions that either have no answers, or have answers even too horrible to express.

Yesterday the UN report on weapons inspections was released.

Today Israel votes and the death toll rises.

Four have died in an explosion at a Gaza City house.

Since last Monday US troops have surrounded eighty Afghans

and killed eighteen.

Protests against the French continue in the Ivory Coast.

Nothing makes any sense today beloveds.

I wake up to a beautiful, clear day.

A slight breeze blows off the Pacific.

It is morning and it is amazing in its simple morningness.

-- from "January 28, 2003"

New from poet and critic Juliana Spahr is the collection this connection of everyone with lungs (University of California Press, 2005), a highly personal and political collection of two long poems written in response to world events. The author of a number of works available on-line as PDF, including Gentle Now, Don't Add to Heartache, 2199 Kalia Road and Unnamed Dragonfly Species, her print works include Fuck You-Aloha-I Love You , Nuclear and Response (originally published by Sun & Moon in 1996, now available as PDF at Brian Kim Stefans' /ubu editions), which was also the winner of the National Poetry Series Award. Co-editor, with Jena Osman, of the international arts journal Chain, she recently moved from Hawai'i to Oakland, California. Built of two highly charged pieces that seem self-explanatory, the collection begins with "Poem Written after September 11, 2001" and continues with "Poem Written from November 30, 2002, to March 27, 2003."

But outside of this shape is space.

There is space between the hands.

There is space between the hands and space around the hands.

There is space around the hands and space in the room.

There is space in the room that surrounds the shapes of everyone's

hands and body and feet and cells and the beating contained

within.

There is space, an uneven space, made by this pattern of bodies.

This space goes in and out of everyone's bellies.

Everyone with lungs breathes the space in and out as everyone

with lungs breathes the space between the hands in and out

as everyone with lungs breathes the space between the hands and

the space around the hands in and out

-- "Poem Written after September 11, 2001"

There is something even eerie about getting my copy in the mail on November 30, 2005, on the anniversary of the beginning of the book's second poem, that starts with this small note:

Note …

After September 11, I kept thinking that the United States wouldn't

invade Afghanistan. I was so wrong about that.

So on November 30, 2002, when I realized that it was most likely that

the United States would invade Iraq again, I began to sort through the

news in the hope of understanding how this would happen. I thought

that by watching the news more seriously I could be a little less naïve.

But I gained no sophisticated understanding as I wrote these poems.

September 11 shifted my thinking in this way. The constant attention

to difference that so defines the politics of Hawai'i, the disconnection

that Hawai'i claims at moments with the continental United States,

felt suddenly unhelpful. I felt I had to think about what I was

connected with, and what I was complicit with, as I lived off the fat of

the military-industrial complex on a small island. I had to think about

my intimacy with things I would rather not be intimate with even

as (because?) I was very far away from all those things geographically.

This feeling made lyric--with its attention to connection, with

its dwelling on the beloved and on the afar--suddenly somewhat

poignant, somewhat apt, even somewhat more useful than I usually

find it.

Political writing is difficult, and there is something deeply personal and abstract in the way Spahr writes her explorations of the world. I've heard poetry described both as an exploration of language and a process in which to try to understand the world, and Spahr's this connection of everyone with lungs certainly works to explore those connections. There are strange things going on in the world, and these two poems ache in their response to but a few of these events. They ache and they explore and they struggle to understand, opening questions that either have no answers, or have answers even too horrible to express.

Yesterday the UN report on weapons inspections was released.

Today Israel votes and the death toll rises.

Four have died in an explosion at a Gaza City house.

Since last Monday US troops have surrounded eighty Afghans

and killed eighteen.

Protests against the French continue in the Ivory Coast.

Nothing makes any sense today beloveds.

I wake up to a beautiful, clear day.

A slight breeze blows off the Pacific.

It is morning and it is amazing in its simple morningness.

-- from "January 28, 2003"

Tuesday, December 20, 2005

from “Missing Persons” (a work-in-progress)

Alberta kept to her journal and let everything else slide. She wrote out her hurts and her hates, and she hid them between the mattress and box spring, away from prying eyes.

After her father died, her mother finally had to learn how to drive, otherwise they were trapped where they were, the three of them in their big empty house. Cabin fever, or stir-crazy. Anything with a higher temperature, deepening to boil. They couldn’t keep depending on neighbours to take Emma in to town for groceries and other errands, or the first few weeks of prepared meals after the funeral, nearly a dozen women in the area, every night, taking turns.

It was Mrs. Friesen, Brian’s mother, who had offered to teach her, afternoons Alberta and Paul watched their mother drive circles around the yard; Mrs. Friesen the passenger, calm. Their mother a wreck.

Emma wound so tight she was kinetic; a spring. A spring that only explodes out before coiling up again, slowly squeezing the air out before another release. Alberta and her brother learned to walk on glass; whether cracked or shattered depended completely on their mother.

Alberta tried to persuade her mother that she should be learning too, but Emma wouldn’t hear it. You’re too young, she said. Paul simply wanted to go along for the ride, pounding gleeful palms on the window or backseat as they drove in circles. As they drove in eventual squares, turning corner on dusty corner around quarters in two mile stretches.

Needless to say, whenever Mrs. Friesen came over for Emma to learn to drive what was once their father’s car, the children were relegated into the house. At least until the engine stopped, and the two women came in for tea.

In the end, Emma drove herself a month before her license took effect. Everyone in town knew. If you were to ask anyone about it, no one would admit to knowing anything, but would have called it special circumstances. You don’t expect three people to stay out in the middle of nowhere without a car, do you? Even less if they have one. Emma something stronger when no one else was looking.

For Emma, beginning to drive herself on roads she thought memorized, lost her way as quickly as she found it again, more than a few times. Roads she thought she knew but less than she remembered. It was like re-learning a language after a stroke, with the frustration of taking longer to get anywhere moving slowly to the joy of discovery, of parts of the land around that she previously hadn’t known.

Once she was a bit more comfortable, she took to driving on Sunday afternoons, by herself or with Paul, in a different direction from the house simply to see where she might end up. She used a series of highway around and the valley below as her boundaries; when she came to one, however she got there, she would return home the way that she knew, back along a more familiar series of turns and straight lines.

For Alberta, it felt nearly impossible to get lost on a grid. There was time, and then there was only time, turning left or right or heading straight through.

Alberta

It seems too obvious to mention that Alberta dreamed of escape, but to where. If there was as much sky as what was under it, her choices would be infinite. Even the direction itself didn’t matter, whether the rise from the west, or sloping down to the east. Each side held its appeal. Or to float down the hidden river that sat miles beneath her.

After her father’s death, shopping with her mother became more tense. Alberta, Emma and Paul, walked through a strip mall an hours drive from the house. Emma, tired but driven. Up at dawn rolling dough for bread, leaving it rise under damp cheesecloth at home. What they would tiptoe around. Dozens of loaves. For a bakery in town. If Emma saw her, or her brother, they would be forced to join in. Alberta working soft brown with her hands. Pounding with whole wheat flour that padded soft sounds on the floor as it dropped, in small handfuls. That made footprints from the dog, or white puff on his dark nose.

In the discount clothing store, Alberta caught a slap from Emma’s hand, on the back of her shoulder. She was humming too loudly again, nearly singing out loud. A habit she got into from spending so much time alone, or with Paul. Releasing the music in her head. The soundtrack to every piece of her, everything that she does. She said nothing, but glared at her mother. She said not a word for the rest of their excursion. She said nothing else for the rest of the day. Her green eyes shot daggers; her green eyes shot knives. Their mother didn’t notice, but Paul did.

Out of water, Alberta felt the full weight of gravity. Her body became stone, her feet turned to lead weights. She felt the air push against her face as she struggled to walk, wondered how it felt to be truly weightless, a creature of air.

To Alberta, there was no such thing as normal. The things that they used to do, ordinary activities were suddenly more difficult, with even the simplest act wrought with new tensions – shopping, going to school, dinner. Every act took on a new and tainted air. At school, no longer just the quiet girl, but the girl with the dead father. Alberta had never lost anyone before, but to Emma, it was far more. As though even their reactions to each other suddenly changed. Who they were, and what they were doing.

Alberta didn’t know if she’s the water or the fuel to her mother’s fire, but knew she was something liquid. Something pure. Her body pushed out impurities with a violent grace. Quickly, and unapologetically.

Mary knew the difference. Of what a parent was supposed to do, and what they weren’t. At least that what she told Alberta. Her own were examples of both, moving to such extremes that neither end she found terribly useful. As she felt, trapped in her own freedoms.

Not that Alberta saw that side, or would have understood. She saw only the freedoms at the end of Mary’s smile. As her own heart lit up. With equal excitement and envy.

During the long drive home, it felt so much longer. She cursed her mother under her breath.

When they reached an intersection, the road across their path firing straight and endless in both directions, Alberta stared so hard into the dot that made the line that the two ends looped around, and connected. Repeating grain elevators and water towers, and secret rail. Where hills and fields rolled wind into empty flow; where no tree, building or body could ever give a sense of space, and where there was no forgiveness.

To Alberta it felt as though they were about to cross an old and sacred line. It felt as though they were crossing something you couldn’t go back on.

(an earlier section of the same work appears here)

Alberta kept to her journal and let everything else slide. She wrote out her hurts and her hates, and she hid them between the mattress and box spring, away from prying eyes.

After her father died, her mother finally had to learn how to drive, otherwise they were trapped where they were, the three of them in their big empty house. Cabin fever, or stir-crazy. Anything with a higher temperature, deepening to boil. They couldn’t keep depending on neighbours to take Emma in to town for groceries and other errands, or the first few weeks of prepared meals after the funeral, nearly a dozen women in the area, every night, taking turns.

It was Mrs. Friesen, Brian’s mother, who had offered to teach her, afternoons Alberta and Paul watched their mother drive circles around the yard; Mrs. Friesen the passenger, calm. Their mother a wreck.

Emma wound so tight she was kinetic; a spring. A spring that only explodes out before coiling up again, slowly squeezing the air out before another release. Alberta and her brother learned to walk on glass; whether cracked or shattered depended completely on their mother.

Alberta tried to persuade her mother that she should be learning too, but Emma wouldn’t hear it. You’re too young, she said. Paul simply wanted to go along for the ride, pounding gleeful palms on the window or backseat as they drove in circles. As they drove in eventual squares, turning corner on dusty corner around quarters in two mile stretches.

Needless to say, whenever Mrs. Friesen came over for Emma to learn to drive what was once their father’s car, the children were relegated into the house. At least until the engine stopped, and the two women came in for tea.

In the end, Emma drove herself a month before her license took effect. Everyone in town knew. If you were to ask anyone about it, no one would admit to knowing anything, but would have called it special circumstances. You don’t expect three people to stay out in the middle of nowhere without a car, do you? Even less if they have one. Emma something stronger when no one else was looking.

For Emma, beginning to drive herself on roads she thought memorized, lost her way as quickly as she found it again, more than a few times. Roads she thought she knew but less than she remembered. It was like re-learning a language after a stroke, with the frustration of taking longer to get anywhere moving slowly to the joy of discovery, of parts of the land around that she previously hadn’t known.

Once she was a bit more comfortable, she took to driving on Sunday afternoons, by herself or with Paul, in a different direction from the house simply to see where she might end up. She used a series of highway around and the valley below as her boundaries; when she came to one, however she got there, she would return home the way that she knew, back along a more familiar series of turns and straight lines.

For Alberta, it felt nearly impossible to get lost on a grid. There was time, and then there was only time, turning left or right or heading straight through.

Alberta

It seems too obvious to mention that Alberta dreamed of escape, but to where. If there was as much sky as what was under it, her choices would be infinite. Even the direction itself didn’t matter, whether the rise from the west, or sloping down to the east. Each side held its appeal. Or to float down the hidden river that sat miles beneath her.

After her father’s death, shopping with her mother became more tense. Alberta, Emma and Paul, walked through a strip mall an hours drive from the house. Emma, tired but driven. Up at dawn rolling dough for bread, leaving it rise under damp cheesecloth at home. What they would tiptoe around. Dozens of loaves. For a bakery in town. If Emma saw her, or her brother, they would be forced to join in. Alberta working soft brown with her hands. Pounding with whole wheat flour that padded soft sounds on the floor as it dropped, in small handfuls. That made footprints from the dog, or white puff on his dark nose.

In the discount clothing store, Alberta caught a slap from Emma’s hand, on the back of her shoulder. She was humming too loudly again, nearly singing out loud. A habit she got into from spending so much time alone, or with Paul. Releasing the music in her head. The soundtrack to every piece of her, everything that she does. She said nothing, but glared at her mother. She said not a word for the rest of their excursion. She said nothing else for the rest of the day. Her green eyes shot daggers; her green eyes shot knives. Their mother didn’t notice, but Paul did.

Out of water, Alberta felt the full weight of gravity. Her body became stone, her feet turned to lead weights. She felt the air push against her face as she struggled to walk, wondered how it felt to be truly weightless, a creature of air.

To Alberta, there was no such thing as normal. The things that they used to do, ordinary activities were suddenly more difficult, with even the simplest act wrought with new tensions – shopping, going to school, dinner. Every act took on a new and tainted air. At school, no longer just the quiet girl, but the girl with the dead father. Alberta had never lost anyone before, but to Emma, it was far more. As though even their reactions to each other suddenly changed. Who they were, and what they were doing.

Alberta didn’t know if she’s the water or the fuel to her mother’s fire, but knew she was something liquid. Something pure. Her body pushed out impurities with a violent grace. Quickly, and unapologetically.

Mary knew the difference. Of what a parent was supposed to do, and what they weren’t. At least that what she told Alberta. Her own were examples of both, moving to such extremes that neither end she found terribly useful. As she felt, trapped in her own freedoms.

Not that Alberta saw that side, or would have understood. She saw only the freedoms at the end of Mary’s smile. As her own heart lit up. With equal excitement and envy.

During the long drive home, it felt so much longer. She cursed her mother under her breath.

When they reached an intersection, the road across their path firing straight and endless in both directions, Alberta stared so hard into the dot that made the line that the two ends looped around, and connected. Repeating grain elevators and water towers, and secret rail. Where hills and fields rolled wind into empty flow; where no tree, building or body could ever give a sense of space, and where there was no forgiveness.

To Alberta it felt as though they were about to cross an old and sacred line. It felt as though they were crossing something you couldn’t go back on.

(an earlier section of the same work appears here)

Monday, December 19, 2005

a note on the poetry of Stan Rogal

In Toronto writer Stan Rogal's ninth collection of poetry, Fabulous Freaks, (Wolsak & Wynn, 2005) he works the poem as collage through writing about the nature of celebrity. Starting from an innocent enough beginning, Rogal tears through the ugly truths (whatever they might be) of writing from such a beautiful place. In the first line of the first poem, "Haunts," he writes "Which craft bends such strange ambition?" (p 13), referencing a number of writers, text and bad jokes (in a poem dedicated to Toronto poet Heather Cadsby, writing "Whatever cads be on this heathered moor"). His willingness and fearlessness to use other forms is impressive, with each collection becoming its own individual project, or series of projects. For some reason, Stan Rogal is one of those writers who never seems to get enough credit for what he does, whether his plays, novels, short stories or poetry collections, one after another after another. Does the volume of such merely build up immunities? In a review of Stan Rogal's In Search of the Emerald City (Seraphim, 2004) in This Magazine (March 2005), Chris Chambers wrote:

"The prolific writer persistently demands what is and will always be highly valuable to readers: time. And if prolific writers value time differently than slowpokes, should we not then assume they value words--the tool of their craft--differently also?

Some writers are fast. Stan Rogal is one of these. The poet/playwright/fictioneer published his eighth collection of poems (his 13th book) last fall. In Search of the Emerald City (Seraphim Editions) is a sequence of 50 untitled poems that manage to spin Rimbaud and van Gogh through the kaleidoscope of The Wizard of Oz. In these punning, poignant, playfully allusive lyric poems, Rogal juggles various themes (going home, growing up, being exiled, going nuts, missing parts, giving up, talent being squandered/abandoned/unrecognized) and bizarre narrative turns (schizophrenia, suicide, asylums, ear slicing, leg losing, cancer) from the true lives of his principals. He smoothly goes about his business, introducing his characters and themes, buffering them with quest tropes from The Wizard of Oz and then loosening up and playing them off each other until some of these poems positively chime with the accretion."

Interspersed with visual collage works, by Rogal as well as collaboratively with Jacquie Jacobs, who was the other half of his collaborative (sub rosa) (Wolsak & Wynn, 2003), Rogal works image against image, and body against body, and letting the poetry come out through the collusion of smashed contrast. Rogal's best writing comes from both the collusion and the writing through myth-making, as in this fragment, the first part of the poem "ONCE UPON A TIME" (p 45), that begins:

Let's begin at the beginning: Once upon a time,

Say. Once upon a time there is a child.

There is a child & there is a journey

(as there is always a child & a journey in such cases).

There is a wood, or an ocean, or a desert.

At any level, a place, where bread crumbs have a snowball's

chance

& Grails remain uninvented.

Hell, it whispers. There is a howl in the wilderness

that threatens a guise of claws, fur, fangs

& smoky breath, set to boil young brains

Ecstatic.

Rogal manages to take what is familiar and completely twist it, moving it around so it becomes something completely other, but in such a way that the reader has remained through the journey. Consider previous works of Rogal's, and his fascination with such cultural icons as Marilyn Monroe and The Wizard of Oz, from references scattered throughout his first collection, Sweet Betsy from Pike (Wolsak & Wynn, 1992) to his Wizard of Oz long poem, In Search of the Emerald City (a much earlier version was published as a chapbook by above/ground press in 1996; it was reworked extensively for the Seraphim edition). His collection The Imaginary Museum (ECW Press) is based on Mallarmé's idea that everyone has "un musée imaginaire" in his head, holding both masterpieces and velvet paintings of Elvis. Other collections, such as (sub rosa) and Lines of Embarkation (Coach House Books), riff off ideas from the outside, becoming texts of reaction, a text responding to something other (as someone once suggested, what all texts really are, in the end). A self-proclaimed “lusty collection,” in (sub rosa), Rogal worked a collaboration, writing a series of poems in reaction to a series of paintings by artist (and partner) Jacquie Jacobs. Going outside writing into visual art is certainly not a new thing, with Stephanie Bolster and Fred Wah being only recent examples using art as a trigger, but the breadth of Rogal’s interest, from science, philosophy, writing and pop culture, brings in a whole other range of ideas and experiences into his poems. His collection Lines of Embarkation (Coach House Books) riffed off ideas from the Douglas R. Hofstaedter book Goedel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid, much in the same way George Bowering’s Delayed Mercy (Coach House Press, 1986) riffed off lines from other writers’ works, from other lines, phrases, ideas, etcetera.

A starting point as well, like predecessors Bowering and Judith Fitzgerald, Rogal allows the language to move through itself, both intellectually and musically moving and working through its own ends. With an ongoing influence by the open-ended form pushed by San Francisco poet Jack Spicer, Lines of Embarkation was a book touching on Achilles, Scylla and Charybolis, Gogol, biology and Mars constructs, it seemed fitting that it would begin with the Leonard B. Merger quote, “The world is a complex, continuous, single event.” and going through a framework not only for the collection as a singular object constructed out of fragments, but Rogal’s poetry as a whole, breaking down into individual collections, yet continuous. It reads as a continuation of the bpNichol mantra illustrated by the open-ended Martyrology, that the text connects, even if only on the basis that it is all written by the same hand. So many of his collections shape and are shaped.

From that collection to this new one, both illustrated with Rogal’s own artwork, intensifies the collage aspect of his poetry, taking bits, jumps, fits and starts from other parts, weaving them into his own. Moving from John Berryman, Jack Spicer, Stanley Cooperman (the late poet and professor at Simon Fraser who taught Rogal), Richard Brautigan and others, they read like threads that have moved through all of Rogal's poetry so far, reaching back as far as the mind can see. Saying, if you want to understand me, go here. In an "author comment" for his collection Personations (Exile Editions, 2001) on the League of Canadian Poets poetry spoken here page, Rogal wrote:

"My work tends towards an attempt to deal with grand ideas or issues, though set within a very personal arena. My first collection of poems, Sweet Betsy From Pike, dealt pretty much with ecology and environment. My second collection, The Imaginary Museum, looked at Art. My third book, Personations, centred around the notion of 'maleness' and can one be a well-rounded, caring, sensitive, intelligent human being and still be a man in the sense of maintaining an identity separate from woman. My fourth book, Lines of Embarkation used science as a stepping off point for developing poems. My fifth book, Geometry of the Odd dipped into chaos theory and my next book, Sub Rosa, will offer various interpretations of a group of eight paintings.

Some singular influences on my poetry (in no particular order) include: Jack Spicer, Marjorie Welish, John Berryman, Richard Brautigan, Judith Fitzgerald, Arthur Rimbaud, Kenneth Patchen, Stanley Cooperman, Michael J. Yates, Viktor Scklovsky and Anne Sexton. Add to this the Beats, the Black Mountain poets, certain Surrealists, the letters of Lorine Niedecker/Louis Zukofsky, the literary theory course I took at York University.

Through it all, I imbue the work with various discourses, from fairy tale to myth to science to art to academia to street vernacular and so on, all in an effort to collapse time and space in order to make everything appear alive and lively here and now. Obviously, some of this comes from my background as an actor and director, which may explain my love of the present-tense verb. In all of this I'm certainly not alone, though it makes for a seemingly tight crowd at times.

Some call my poetry modern, others post-modern, some call it lyric, others call it language; some see much of it as stream-of-consciousness, others read it as tight and well-thought out; some see it as imagistic, others as idea oriented; some see it as wildly subjective, others as coldly objective. This I perceive as a good things and wouldn't disagree with any one's interpretation. I'm happy that someone reads it and gets something out of it. Overall, I write poetry because I get a kick out of it and it gives me an opportunity (a way) to explore and experience the world through language."

In a recent interview he echoed the sentiment, where he said: